‘The NHS is, rightly, the biggest reason most of us are proud to be British,’ Jeremy Hunt said in his Budget this week. The Chancellor isn’t wrong: according to polling from last year, the health service is the top reason to be proud to be British among 54 per cent of British citizens; far more than our history (32 per cent), culture (26 per cent) or let alone democracy (25 per cent). But this is not something to be celebrated; instead, it is illustrative of the malaise that today affects British national identity.

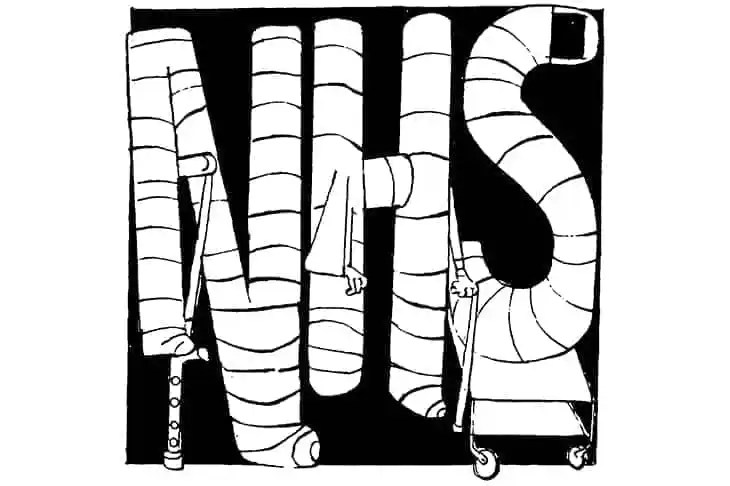

It is a sad reflection on how feeble British national identity has become

Traditionally, there are two ways to look at national identity. One of them is ethnic. According to ethnic nationalists, a shared ancestry is what makes a nation’s people who they are. To be British, on that view of the world, your ancestors must have arrived onto the British Isles hundreds of years ago and had looked much as you do today. Such a view of national identity has, not without reason, largely fallen out of favour.

The other way to look at national identity is civic. Civic patriots, rather than emphasising the role that shared genetic heritage plays in the soul of a nation, focus on the role of those less tangible characteristics that really define a nation’s soul: shared values, interests and culture. To them, to be British means to sing the anthem, have read Blake and Tennyson, feel a unique attachment to liberty, admire St. Paul’s Cathedral, or even listen unfailingly to the Monarch’s Christmas address. Crucially, on this view of nationality, one does not have to be born British: one can become British. And, for all the pros and cons of the NHS, I could not see myself becoming any more or less British on account of it.

The UK nowadays increasingly lacks the kinds of things that could unite us around a shared national identity, which is why the Chancellor was right to say that the NHS is what unites us the most. But this is not because the NHS is a powerful unifying force: it is because we have lost the sorts of things that should truly be uniting us instead.

It is no secret that levels of patriotism have been flailing in recent decades. Less than half of British under-24-year-olds are proud of being British. Well over a third of military-age Brits would refuse to serve if called up, and a meagre 7 per cent would volunteer for military service if a world war broke out. By contrast, even in the Great War – when conscription was notoriously unpopular – 1.5 million men volunteered for service within the first year of the War. This was well over a quarter of all military-aged men in the UK at the time.

Let’s not blame those who have lost – or never even discovered – a love for Britain. Many never had that bittersweet feeling of both pride and sorrow when reading the penultimate stanza of the Charge of the Light Brigade or longed for England’s green and rolling hills because those feelings were never aroused in them. Those are the feelings you need to build a national identity around them, not being grateful for getting a free visit to the GP.

Alongside a decreased feeling of patriotism, we have seen an increase in other forms of identity politics. People are increasingly divided across the lines of race, sexuality, gender and politics, with that becoming their primary identity instead. Around 40 per cent of Brits would not even date somebody who voted for the opposite party. Political alignment, instead of national belonging, has become a marker of tribalism. Consequently, sharing little in common with other Brits, young people in the UK increasingly favour an authoritarian government that has no need to consider common interests. After all, only such a government has the ability to pursue the interests of a political minority against the will of the average citizen.

Even more worryingly, the loss of a British national identity may lead to a return from the shadows of ethno-nationalism. In recent years, the UK has been a prime import destination for American identity race politics. As British identity weakens, for many, race will become their primary identity, with nationality only secondary. Racial divisions across the UK will be emphasised, and, consequently, deepened. Incidents like the one in Leicester two years ago or in Peckham last year could become commonplace.

For the NHS to be ‘the biggest reason most of us are proud to be British’ is not good enough, and it is not right. It is a sad reflection on how feeble British national identity has become. Unless that identity is restored, internal fractures will keep tearing at the fabric of British society – until it comes apart at the seams.

Comments