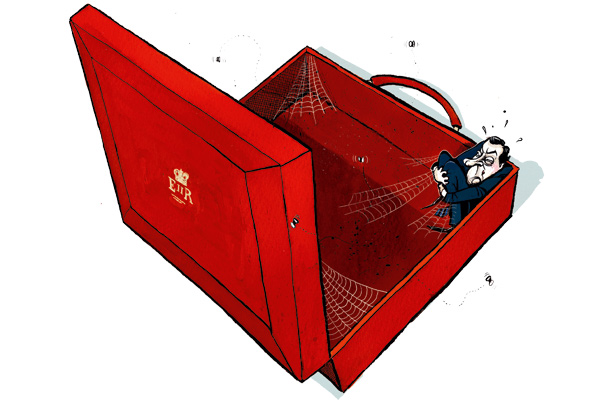

Before every Budget, George Osborne always seeks the advice of various MPs. He usually doesn’t heed it but it’s a good way, he thinks, to keep the troops happy. As the economic headwinds have strengthened, this advice has tended to be increasingly radical and in a recent meeting with the Free Enterprise Group of Tory MPs, the Chancellor made clear he was in no mood for it. ‘Look,’ he told them, ‘I tried radicalism in last year’s Budget, and I had blowback for it. So I’d take quite some persuading to do something radical this time.’ The MPs left with the clear impression that he is now preparing what will be, in effect, an empty Budget.

If Osborne were planning to change course before the next election, he’d have to do it now. The plan he set out three years ago had the Olympics marked down as a turning point — assuming that debt would by then be under control and he’d be mulling some celebratory tax cuts. Instead, Britain seems mired in what is, officially, the worst recovery in history. Progress on the deficit, Osborne’s defining mission, has halted. The AAA credit rating he once prided himself on has gone and youth unemployment is reaching crisis levels. If the Chancellor had a secret plan for growth, now would be a good time to produce it.

The Tories growing impatient with Osborne have a fairly clear idea what needs to be done: bold tax cuts. If all this extra debt-financed spending hasn’t worked (Britain will have borrowed an extra £12,000 by the time you finish reading this sentence), then tax cuts should. Proposals range from thick documents (such as the 2020 Tax Commission report) to ideas from various Tory radicals. Before Steve Hilton quit as the government’s chief strategist, he wanted corporation tax cut below Irish levels. Others propose a Swedish-style tax cut for the low-paid — which moved so many into work that it almost entirely paid for itself. Capital gains tax could be abolished, or employers’ National Insurance suspended.

But word from the Treasury is that none of this will happen. ‘If we didn’t need to produce a Budget this year, we wouldn’t,’ says an aide. So there will be the usual whale spray of policies: a fuel duty cut here, help for the low-paid there. Osborne is a backgammon lover: a game where one’s own strategy is dictated by that of one’s opponent. Things may be bad for him, but the important thing is that they’re worse for Ed Balls. So his Budget will be a continuation of his five-year plan, not a rupture.

Even as shadow chancellor, Osborne never burnt to do things differently — signing up the Tories to Labour’s spending plans as if to close down the economic debate. He has always been suspicious of those he regards as Tory ‘ideologues’, who prescribe tax cuts for every malady, and whose zeal he blames for three successive election defeats. Osborne is an incrementalist, preferring the chisel to the axe. As Chancellor, he has defined himself around this approach, saying that he is a ‘fiscal conservative’ as opposed to his ‘Reaganite’ colleagues.

When Nigel Lawson delivered his radical tax-cutting Budget almost exactly 25 years ago, the young Osborne was listening through a pocket radio on the bus on the way home from school. He still remembers where he was — Hammersmith Bridge — when Alex Salmond was thrown out of the Commons for protesting over cutting the top rate of tax from 60p to 40p. Cutting taxes for the rich, the teenage Osborne concluded, is deeply unpopular. It was something he learnt anew last year, when he cut the 52p rate of tax. Those close to him say he is still angry at the lack of support he had from business leaders during the ‘blowback’ which followed his Budget. The new top rate of tax, a far-from-competitive 47p, looks here to stay.

With Osborne, everything is political. No economic policy is made without a view to how it would sound in an election slogan, and he believes he has enough ammunition. By raising the tax threshold, he can claim to have cut taxes for 25 million — though the amount is, according to Policy Exchange, just £1.51 a week. He spoke about abolishing the deficit by the election; now he’ll still have the biggest deficit in the Western world. But he sees a virtue even in this: he can to ask voters to let him finish the job. Those who discuss strategy with Osborne say that the only thing he believes his economic strategy needs is time for his reforms to bear fruit.

This confidence is not widely shared in the party. ‘The most important three issues between now and the election will be economy, economy, economy,’ says one. ‘And our economic policy is neither fish nor fowl.’ There is an irritation that, having won the argument for austerity, Osborne takes all the political pain while making little economic progress. During the Labour years, total state spending rose by an extraordinary 60 per cent, yet Osborne has reduced it by just 3 per cent in three years. The Chancellor’s allies say this is more than even Thatcher dared, and that corporation tax is (slowly) tumbling from 28p to 21p, putting Britain atop surveys of desirable places to do business.

So Osborne urges patience: the growth will come. The problem is that it has already come to Germany, Canada, Sweden and Austria, who have all seen their economies recover to pre-crash levels, even adjusting for population growth. Britain is now not expected to manage this until 2017, a full ten years after the crash. This leaves us midway through a Japanese-style ‘lost decade’, and that’s if all goes well. The Budget small print is expected to indicate that, adjusting for inflation, salaries will not be back to pre-crash levels until at least 2027. To lose one decade is unfortunate; losing two may be seen as unforgivable.

If it doesn’t feel like a lost decade, it is because of Osborne’s main economic strategy: artificially low interest rates. Even the loss of the AAA rating has not altered what will be the Chancellor’s biggest budget boast: that his government can borrow cheaply, at just 2 per cent. Greece and Spain would kill to be able to pay such rates but neither has a central bank capable of printing money to buy government IOU notes. This is what is happening in Britain, and does much to explain why Osborne is so relaxed about an empty Budget strategy. The real work is not being done in the Treasury, but the Bank of England.

Every so often, Osborne gives a hint of his tactics: that he is a fiscal conservative ‘but a monetary activist’. While deeply sceptical about using taxes to engineer a recovery, he places far more faith in quantitative easing, which is by now the biggest money-printing exercise ever undertaken by a major economy. By now, some £375 billion has been digitally created by the Bank of England, and used to buy government bonds. A full 29 per cent of Treasury UK government debt is owed to the Bank of England, which is 100 per cent owned by the Treasury. The government machine is lending money to itself: it is every bit as weird as it sounds.

And the effects? A few months ago, the Bank of England released a paper showing what happened after the first £325 billion it printed — to boost the value of assets, apparently, including houses, paintings, rare wines and antiques. Great news to those who possess such items, but bad news for those who don’t and are still confronted with the extra general inflation. The Bank then spelled out the effects. The richest two million households are, on average, about £127,000 better off as a result of QE, your average household is about £9,000 better off and the poorest two million are worse off by an average of £310. If the fictional Alan B’Stard was to be made Chancellor and pass a budget to reward the rich and screw the poor, he could do little better.

The advocates of QE believe it has saved the economy, and this may well be so. But at what cost? The scrutiny that falls upon every dot and comma of Budget statements is almost entirely absent from the largest money-printing programme in the world. It may well mean heavily subsidised millionaires, and pensioners living on £5 a day because the value of their annuities has been shot to pieces. Labour won’t criticise; it started QE, and continues to support anything which makes debt cheaper. No matter how dramatic its effects, QE is judged just too complex (or dull) for Budget-style scrutiny.

The importance of cheap money policy explains the excitement about the arrival of Mark Carney, who runs Canada’s central bank. As one No. 10 official puts it: ‘The day when Mark Carney sits down will be far more important than the day when George Osborne stands up.’ With so little importance placed on Budgets, it is the Governor of the Bank of England who is taking the lead on UK economic strategy. Hiring someone of Carney’s global stature was a coup for Osborne, but no one is quite sure what he will do. The future of Osborne’s easy money strategy lies in his hands.

A recovery built on debt, of course, is no recovery at all. Nassim Taleb, an economist-philosopher greatly admired in No. 10, argues that it is madness to pursue economic growth for its own sake. If a government borrows £500 billion and expands the economy by £300 billion, then is this really a success, or just another debt-fuelled illusion?

Another one of Taleb’s own rules is never to trust long-term economic forecasts, because they are so laughably unreliable. Osborne may take some comfort from this: the statistical horror story he has to announce in his Budget outlook may not come to pass. His strategy is not radicalism but Micawberism, a hope that something might turn up. It’s mixture of stubbornness, caution, resolve and astonishing optimism. It has left him dependent on the two oldest tools at a Chancellor’s disposal: to hope and pray.

Comments