The last major show of paintings by Edward Burra (1905–76) was at the Hayward Gallery in 1985 and I remember visiting it with a painter friend who was rather critical of what she called Burra’s woodenness and lack of movement. At the time, I was impressed by her criticisms, but now they rather seem to miss the point. Burra made highly stylised images of people (often actually in movement) which are mostly about the darker side of humanity and the ways in which we distract and amuse ourselves in the face of despair. What might have been dreary little genre pictures he painted with such wit and humour and generosity of spirit, with such a richness of colour and complexity of pattern-making, that the oddness of his subjects is caught up and translated into something much larger: in fact, into art. And the wonder of it is that he painted almost entirely in what so many dismiss as the maiden aunt’s medium — watercolour.

Since that 1985 exhibition, Burra’s fortunes have sunk somewhat, and his work has been little in evidence in museums and galleries. It wasn’t until a single-room display at the Tate in 2008, of his paintings of black people in Harlem, that a wider audience was given a real taste of what Burra could do as an image-maker. Meanwhile, his prices in the auction rooms began to take off, and have subsequently risen into the millions. Burra was evidently catching the attention of collectors and museum curators once again, so it was only a matter of time before the public would be allowed proper access to his work.

The present exhibition at Pallant House is a wonderful celebration of Burra, but it is typical of the ghettoised mentality of our art establishment that it could take place only out of London. The Tate will give an artist like Burra a single room at Millbank, but not a full retrospective; such treatment is reserved for the more conceptual and fashionable practitioners who fit the current orthodoxy. Whatever happened to the kind of eclecticism the public has a right to expect?

Perhaps things are finally changing, for I gather the Tate has responded to considerable popular pressure and at last sanctioned a major show of L.S. Lowry for 2013. That bodes well. But, in the meantime, exhibitions of Modern British painters, such as Sutherland or Burra, are left to enterprising galleries in the provinces. And it should be said at once that Pallant House has done a very good job of re-presenting Burra, and has packed a great deal into its not exactly vast temporary exhibition galleries. This is an exciting show, and for many it will be a revelation. The first room puts the viewer at once in the thick of the action, and what stylish action it is, for Burra was a superb designer of paintings. Here is gathered a group of very high-quality small paintings, beautifully laid out against pale-blue walls, surrounding a cabinet of documentary material, mostly photos and letters.

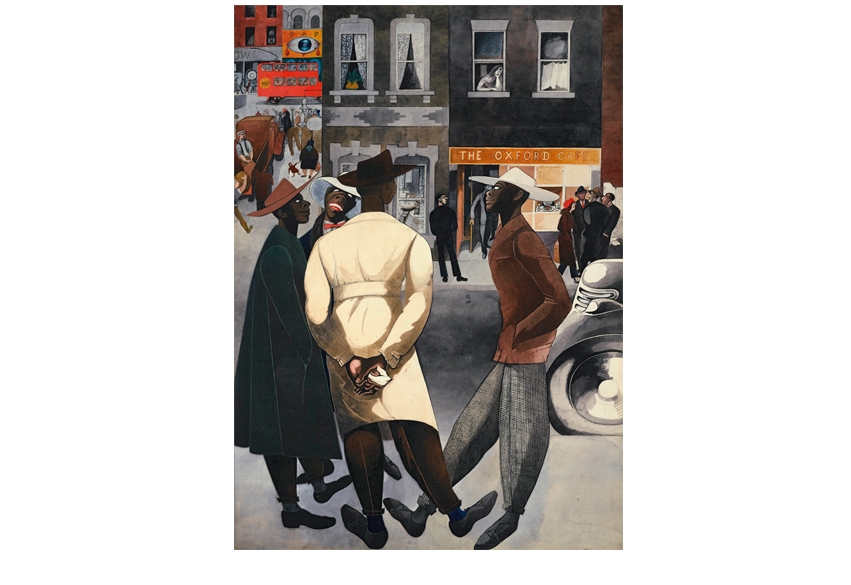

Among the familiar images of low life in foreign cafés, bars and nightclubs, full of strange-looking figures bulging provocatively despite their general unattractiveness, are a number of lesser-known paintings. So we have old favourites such as ‘The Snack Bar’ and ‘Harlem’ from the Tate, both 1930s paintings, and then a marvellously orchestrated cramped 1920s composition called ‘The Common Stair’, recently sold at Sotheby’s, and a tall, thin, blue-grey painting called ‘The Nitpickers’ (1932), depicting a long street in Toulon or Marseilles, with a gaggle of off-duty tarts relaxing in the foreground. Lots of paintings have come from private collections and are little-known, such as the unusually seductive ‘Les Folies de Belleville’ (1928). Burra’s figures are not always grotesque, but he clearly had sympathy for the less prepossessing. The mood of disquiet edges into menace from time to time: in the Soho painting ‘Zoot Suits’ (1948), a Cyclops stares from one of the curtained first-floor windows.

The next room is painted a warm pinkish red on which are displayed Burra’s most surreal works: a disturbingly mechanical collage from 1930 called ‘The Eruption of Venus’, a witty and highly sexualised metaphorical image entitled ‘The Duenna’ and the horrific anti-war image ‘Skull in a Landscape’ (1946). Burra somehow manages to stay the right side of caricature in these works, even in the hell-hot satire ‘John Deth (Homage to Conrad Aiken)’, which owes so much to George Grosz and Otto Dix. In fact, Burra is least effective when flying under borrowed plumes, and his variations on European contemporaries (Ernst, Magritte or the Germans) are not nearly as potent as his own imaginings. The third room introduces various other elements such as still-life and restates Burra’s abiding interest in the macabre: ‘It’s All Boiling Up’ and ‘The Straw Man’ are images of such lasting effect because they plumb the depths of human malignity.

Undoubtedly, humanity was Burra’s greatest subject, but in his last years he seemed to lose interest in people somewhat and turned to painting the landscape. If I have a criticism of this gripping exhibition, it’s that there are not enough of Burra’s late great empty landscapes on show. He was always a weird painter, but the late landscapes are unusual in different ways: vast panoramas, they are exquisitely painted but nearly always haunted by something unexpected. There are many other pleasures, however, including a room devoted to Burra’s stage designs. A lot to absorb, and even some footage of the man himself avoiding answering questions: hilarious and moving.

Accompanying the Burra exhibition is a book that doubles as catalogue and monograph, published by Pallant House in partnership with Lund Humphries (£35 in hardback). I can scarcely be expected to be impartial about this publication as I have contributed an essay to it about Burra’s landscapes, but it’s full of good things. The book is edited and largely written by Simon Martin, the exhibition’s curator, with an introductory essay on Burra’s life and letters by his biographer, Jane Stevenson. The reproductions are on the whole rather dark and don’t do justice to Burra’s surprisingly luminous paintings, so there’s no excuse not to visit the show and see his remarkable work at first hand. Should you miss it in Sussex, the exhibition tours to the Djanogly Art Gallery in Nottingham (3 March to 27 May).

Comments