John Williams’s brilliant 1965 novel, Stoner, was republished last year by Vintage to just, if surprisingly widespread, acclaim and went on to sell tens of thousands of copies and appear in many Books of the Year lists. Written with a sober perfection of style that suits its subject — the elegantly factual glowing with a careful lyricism — Stoner depicts the life of a diligent Midwestern literary academic that is often one of quiet desperation but is periodically shot through with luminous moments of insight and love.

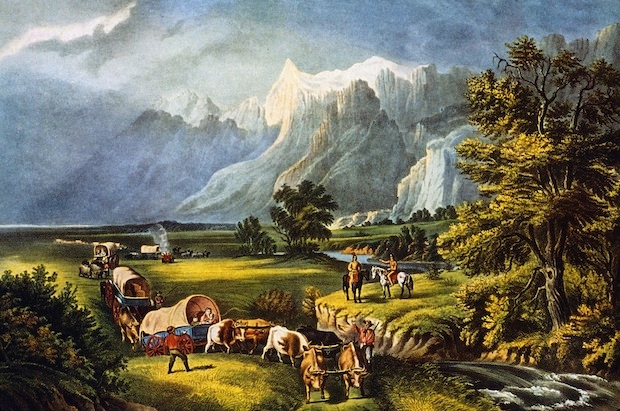

Now Vintage have republished Williams’s earlier novel, Butcher’s Crossing. Executed with the same fastidious observation and restraint, it is nevertheless a very different book, a bleak and rugged western adventure set in the 1870s that follows Will Andrews, an idealistic young Harvard drop-out, keen to commune with Nature. He pursues this impulse on a buffalo hunt in the Colorado Rockies, where experiences of hardship and violence are so prolonged and extreme as to make all such thoughts seem vaporous.

The novel is prefaced by two superb epigraphs. The first, from Emerson’s essay ‘Nature’, exalts in the kind of numinous contact with the natural world that our hero is seeking. The second, from Melville’s The Confidence Man, warns against this aspiration as liable to end in a freezing death on the prairie. The two canonical sources are indicative: Williams intends this novel to be set firmly in the American tradition. Like many literary novels about the West, Butcher’s Crossing has a strong element of allegory and national myth.

The constituent parts of the myth are sometimes worryingly familiar — the scary two-horse town, the adventure-hardened types, the tender-hearted prostitute — but the expertise of the writing vivifies the stock characters and set pieces of which the novel is composed. In the mountains, the scenes are exceptionally vivid. The sensation of thirst, as characters trek for days without water, the discovery of the valley full of buffalo, the days of ceaseless killing, what it’s like to flay a buffalo badly — half the skin still adhering, clumps of flesh hanging from the ragged hide torn off — or the winter whiteout that delays the group’s return for months, are descriptions impossible to forget. All of this action lasts long enough to put the reader in the same entranced state of brainless physical absorption that Will Andrews experiences.

With money and guns and a small party of fractious men, there is room for the kind of game theory machinations of conflicting self-interest that drive The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, but Williams does not exploit them. Instead, fortunes turn on the unpredictable power of the natural world and the punishing opacity of the free market. The novel culminates beautifully in action and stingingly in thought with the expression of the only philosophical consolation it has to offer: a kind of grand stoicism in the face of an uncaring universe.

It is here that the worlds of Butcher’s Crossing and Stoner intersect. Both are tough-minded and disillusioned but susceptible to beauty and human warmth. They are also supremely well-written and built to last.

Comments