Counter-insurgency operations, as any army officer could tell you, are a messy business in which the consequences of failure are always easier to measure and appreciate than the rewards of victory. Moreover, even limited success in one area – the destruction of the enemy’s ‘human resources’, for instance – can be offset by the manner in which that success is achieved. Short-term success cannot be confused with long-term stability. And therein lies one of many paradoxes: counter-insurgency operations frequently involve starting fires to put out other, larger, fires.

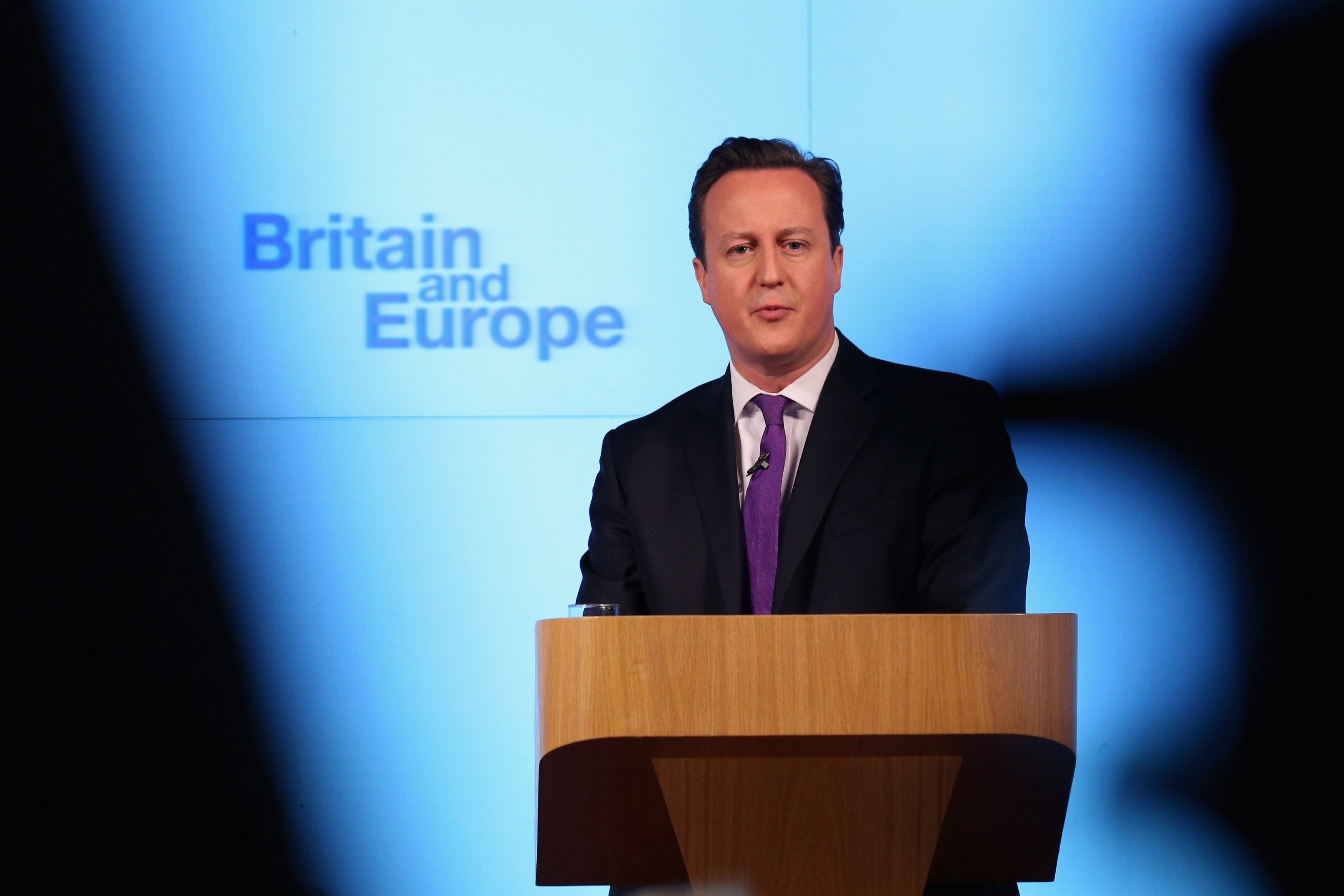

Politics, as David Cameron might now tell you, is often much the same. The Prime Minister is, this week, fighting twin insurgencies. Each threatens his position, his authority, and his potential legacy. In each instance, he finds himself having to pacify a vocal minority without, he hopes, angering the so-called ‘silent majority’ upon whose judgement his success – or failure – ultimately rests.

The problems of Scotland and Brussels are more similar than sometimes supposed. The Scotland Bill, debated by the Commons this week, is a pacification strategy designed to appease the troublesome tribes in the northern part of the kingdom; the Prime Minister’s attempts to cobble together a semi-credible “renegotiation” strategy for his relationship with the EU is, likewise, an attempt to make a weak hand seem like a strong one. It is an attempt to forestall rebellion in the south.

In each instance, however, the real target is less those who are notionally being appeased – the SNP and Tory euro-sceptics, respectively – than the much greater mass of folk who are weary of these endless constitutional skirmishes. Though the Scottish Nationalists are fond of conflating party and national interest they no more speak for Scotland than right-wing euro-fanatics within the Tory party speak for Britain. Most of Scotland voted No last September. The question ‘What kind of country do you wish to be?’ received the answer ‘A British one’.

Of course the SNP can be no more appeased than can Cameron’s own internal anti-european critics. No possible Scotland Bill could buy off the Nats just as no possible – or even imaginary – european renegotiation could satisfy the Better Off Out brigade.

But in each instance Cameron must give the impression of doing something so he can secure both some hard-won territory and, just as importantly, some breathing space. In each instance he needs to sell the proposition that, look, he’s been entirely reasonable about these matters even as he is tormented by thoroughly unreasonable opponents. What more, gosh, could he have done? Give the guy a break and, even, just a little credit.

That reasonableness matters. Cameron must contain the threat posed by both the SNP and his own internal critics without inflaming voters for whom neither the Scotland Bill nor the EU-renegotiation are matters of consuming passion. Those voters who would, all things considered, prefer a quiet life. Most voters, in other words. Boredom and inattention are Cameron’s chums.

Cameron’s response to each of these challenges to his authority was born of weakness. In neither case could he welcome the fight; in each he has been forced to respond to events beyond his control and has chosen to do so by delivering the smallest offer he thought he could plausibly escape with making. (The Scotland Bill, that said, is a much bigger deal than the european ‘renegotiation’ even if the SNP will still, always, cry foul.)

Nevertheless, if, for the sake of argument and illustration, just 35 percent of Scots had voted Yes last September there might scarcely have been a need for a new Scotland Bill at all. Similarly, if only one in ten English Tories were Outers then there’d be no need for an EU referendum either.

The other thing about counter-insurgency operations, of course, is that victory is hard to define. It is often a case of drawing succour from the contemplation that matters could, if differently arranged, be very much worse. That is the position in which the Prime Minister finds himself now. The trouble is that Cameron cannot really buy off the monomaniacs and nor, in the end, can he crush them without risking becoming a recruiting officer for their cause. Which leaves him making a tricky pitch to middle and majority Britain: stability through fear of something worse.

But his Scottish problem is not going to disappear and nor, whatever the result of this new referendum, is his Brussels difficulty going to be solved by anything so simple as ‘winning’ a plebiscite. The causes of these insurgencies lie too deep for that and neither can be bought off easily. The troublesome warlords Cameron must deal with care too much about the one thing about which they care for that to happen. The best Cameron can do is keep a lid on these problems.

That’s not very heroic and not the kind of thing that merits heralds and trumpets but it is, in the present circumstances, the best the Prime Minister can do. In Scotland, he must cede ground to retain an uncomfortable, provisional, status quo; on europe he must persuade voters that a minor skirmish is, in fact, a major victory. These aren’t just the best deals available, they are, crucially, the fairest, most reasonable, deals.

If you can’t win peace you can at least settle for winning time. That’s another uncomfortable lesson from counter-insurgency operations.

Comments