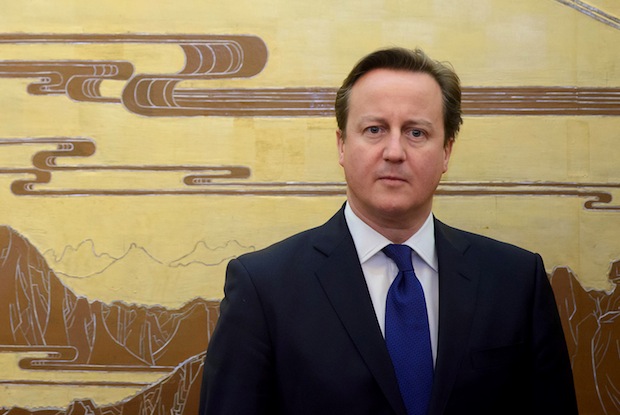

European elections are normally an afterthought in British politics. As even David Cameron admits, most of us struggle to remember who our MEPs are. Two-thirds of us don’t even bother to vote for them. But this year, the European elections are threatening to dominate politics.

Talk to Tory ministers and MPs about the year ahead, and they all look nervously towards May, because they know that the Conservative party is in real danger of coming third in a nationwide election for the first time in its history.

In and of itself this need not matter too much. The trouble is that a third place finish would send the party into a panic from which it might not recover before the general election. In the aftermath of being beaten by Ukip, there would be demands for an electoral pact with Nigel Farage, for an explicitly ‘outist’ European policy and for a string of more distinctively right-wing policy positions, all of which would drive the Tories away from their central argument: you can’t trust Labour with the economy.

All Tory MPs know that the party’s manifesto for the European elections will have to set out some more detail on his policy of renegotiation followed by a referendum. MPs of a more uncompromisingly Eurosceptic bent are flexing their muscles, pushing for a tougher line.

The most ostentatious example of this is the letter organised by Bernard Jenkin — a Maastricht rebel who became a shadow minister under Hague, Duncan Smith and Howard, and is now chairman of the Public Administration Committee — calling for a UK veto over all European laws. Since last month, when the letter became public knowledge, Tory MPs have known that William Hague’s Foreign Office regarded the idea as a non-starter. But — and this is what should worry the leadership — that hasn’t stopped 95 of them signing it. The letter’s backers even regard its rejection as having served a useful purpose in flushing out Hague’s true position. ‘People can now see where he really is,’ one senior Tory backbencher observes.

Jenkin’s letter has annoyed the Cameroons. They are infuriated by his success in drumming up signatures for it, and his cleverness in minimising the differences between his position and the Prime Minister’s. One minister close to Cameron complains, patronisingly, that ‘the problem with Bernard is that he is a quarter plausible’.

Cameron may well be irritated, but he’s also trapped. Having declared last January that he wants to renegotiate Britain’s membership of the European Union, he has to define what he means — and decide how much detail to include in the Tory manifesto for the European elections. There was meant to be a meeting to discuss the manifesto last week, but it was postponed and has yet to take place. (That’s not incompetence, sources inside Conservative Campaign Headquarters insist; it’s just that the party’s Australian campaign manager, Lynton Crosby, is still away.)

One consolation for Cameron is that the lifting of the transition controls on immigration from new EU members Romania and Bulgaria has not led to any great surge in arrivals. If it had, it would have tied Europe and immigration even more closely together in the public’s mind. As of now, the Romanian ambassador is saying that only 24 of his countrymen have taken advantage of their enhanced opportunity to move to Britain.

This absence of a flood of Romanians and Bulgarians is a blow to Ukip. Farage himself has always been clear, as he told The Spectator last year, that ‘a lot of Ukip’s success will depend on this issue’. If Romanian and Bulgarian immigration doesn’t live up to the hype, it’ll blunt one of his party’s most potent campaigning tools.

But Farage is a skilful politician and he’ll find other issues to tap into. Indeed, the rapid rise of Patrick O’Flynn, a Daily Express journalist, in the Ukip hierarchy suggests that the party grasps the need to focus on the frustrations of middle-income voters and their anger with the political class. O’Flynn, who will soon become the party’s director of communications, promises to professionalise the Ukip operation. He could be as important to Ukip’s political development as Peter Mandelson was to the Labour modernisation project.

But the biggest challenge for Ukip is to maintain the momentum that the European elections are likely to impart. Ukip attracted 16.5 per cent of the vote in the last European elections. By the general election in 2010, it had fallen back to 3 per cent. If Farage can avoid another general election squeeze on that scale, it’ll become very difficult for the Tories to win. Labour election planners now expect Ukip to poll 8 per cent or more in 2015, which would make it pretty much impossible for Cameron to assemble a majority.

On the economic front, however, there is good news for the Tories. The fall in inflation to 2 per cent should both ease the squeeze on living standards and reduce pressure for an interest rate rise. There are also signs that voters will soon begin to feel better off. After tax, median earnings are now rising faster than prices. If this trend continues, then Miliband’s big argument — that there need to be structural changes to the economy to deal with the ‘cost of living crisis’ — will lose much of its appeal.

At this stage in a parliament, Westminster would normally be obsessing about when the Prime Minister might go to the country. The Fixed-Term Parliaments Act puts a stop to all that, at the price of making the election campaign season even more protracted than usual. Cameron knows his rivals will be in full campaign mode soon, if they aren’t already. So it’s all the more important for him that the Tories don’t spend the next 12 months rowing about Europe. If they do, he won’t have much time left to make his case to the country.

Comments