A big problem with the coming European Union referendum is that voters won’t know what voting ‘leave’ means. If we do decide to quit, it will be a leap in the dark that could cause huge damage to the country. There is, therefore, a strong democratic case for spelling out the terms of our departure before it becomes final.

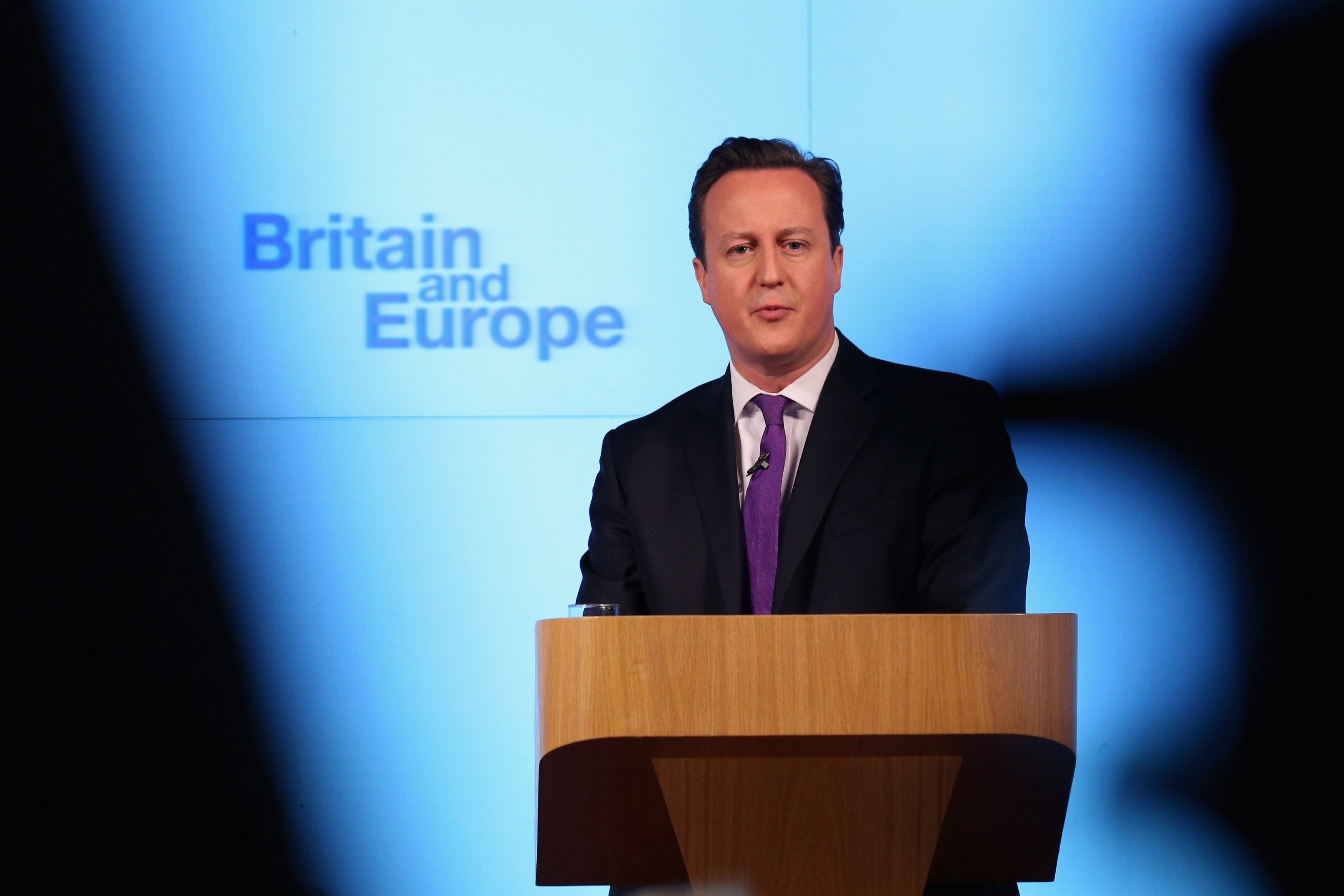

The best way of achieving this would be for David Cameron to launch a double negotiation. As well as trying to improve the terms of our membership – the focus of his current talks with the EU – he would clarify our potential divorce deal. The voters would then get to compare two clear options and choose the one they prefer. If something like this had been done with Scotland, we wouldn’t still be wrangling over the Scottish issue.

Such a twin-track negotiation would be an alternative to the ‘double referendum’ that some Eurosceptics have been pushing but which Cameron has now scotched. Under their scheme, the first plebiscite would take place after the Prime Minister finishes his negotiation on the terms for staying in. This would determine whether we want to leave ‘in principle’. If we said we did, there would then be a discussion of our exit terms. After this, there would be another referendum to decide whether we really want to quit.

Although this convoluted idea has been justified by Eurosceptics partly on the grounds that it would be democratic, the real purpose has been to de-risk the ‘leave’ option. It was floated in June by Dominic Cummings, now a leading light in Vote Leave, one of the groups campaigning for us to quit the EU. He figured that more people might be tempted to vote ‘leave’ if they knew that they’d get a chance to review the divorce settlement before it became final.

Although Downing Street has rightly squashed this idea, it would still be good to give people a clear idea what they are voting about. This is where the twin-track negotiation would help. Not that it would appeal to Eurosceptics – as it would force them to confront what sort of ‘out’ arrangement they prefer. They want to avoid having this argument in public, as they think it would sow confusion among voters before the referendum. But it would be more honest to thrash it out so the electorate knows what it is letting itself in for.

One option would be to stay in the EU’s single market, on the grounds that it accounts for nearly half our trade. If so, the nearest model would be Norway, which has full access to the EU market without being in the club. The snag is that Oslo has to contribute to the EU budget and to follow all the single market regulations without getting a vote on them. That hardly seems an advance for British sovereignty. We currently sit at the top table with the third largest number of the votes after Germany and France. Norway also has to allow free movement of people, which wouldn’t appeal to those who want to quit the EU in order to stop Romanians and Poles coming to Britain.

Not surprisingly, Vote Leave doesn’t like this idea and says it would, instead, negotiate an ad hoc trade deal with our former partners. The snag is that, if it really insists on no free movement of people and no budget contributions, we won’t get much access to the EU market. In particular, we won’t get full access for financial services, which would be a blow to our biggest industry. We might well also face tariffs on exports of goods such as cars. And, insofar as we still sold goods into the EU, we would have to follow its product regulations without a vote on what those were. After all, we’d be negotiating with a bloc six times our size.

The ‘leave’ campaign, of course, will disagree with this prognosis. That’s another reason why a twin-track negotiation would be a good idea. It would provide a way of testing the Eurosceptics’ optimism. Let them set the red lines for their divorce deal and then Cameron can go into bat on that basis and secure the best deal he can.

Even if one was persuaded of the merits of a twin-track negotiation, one might think the whole idea is far-fetched. But it is not as pie in the sky as the double referendum idea. For the idea to fly, Cameron merely needs to decide it is in his interest.

One reason he might find this appealing is that it could increase his leverage to secure a better deal to stay in the EU, as it would focus the minds of the other countries, which are keen for us to stay a member. A twin-track negotiation would also increase the chances of people voting to stay in – as, once the British people saw the new membership terms side-by-side with what would probably be an unattractive divorce deal, they would choose the former. Cameron should like that. After all, if he advocates staying in the EU and the people vote to leave, he will have to resign and may go down in history as one of Britain’s worst prime ministers.

Hugo Dixon is the author of The In/Out Question: Why Britain should stay in the EU and fight to make it better

Comments