Everyone giving evidence to the Covid Inquiry has their own corner to defend. And every ex-prime minister has a part of their premiership that they spend the rest of their life talking about and trying to justify.

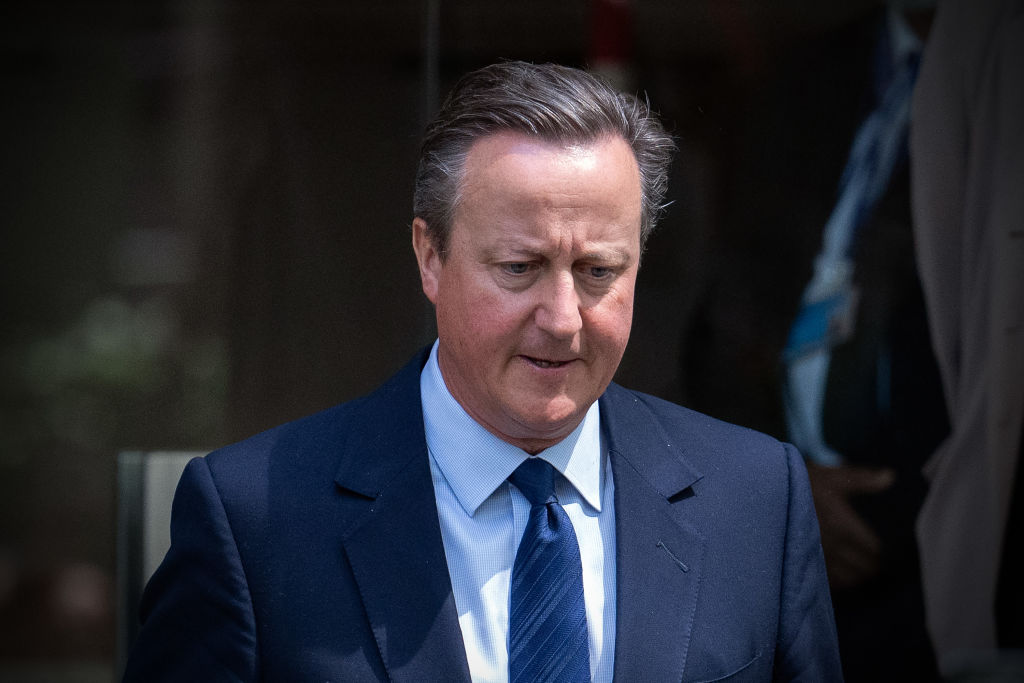

For David Cameron, it was his public spending cuts. Experts blame them for the health service being in very poor shape when the pandemic arrived. The former prime minister had his session before the inquiry this morning, and unsurprisingly he was keen to argue that these spending cuts weren’t just unavoidable, but essential to ensure the country’s economy was in a robust shape so it could afford to respond to crises including pandemics. He said:

Our whole economic strategy was about safeguarding and strengthening the economy and the nation’s finances so we could cope with whatever crisis hit us next. And I think that’s incredibly important because there’s no resilience without economic resilience, without financial resilience, without fiscal resilience.

The problem with Cameron’s argument was that while it is unarguably better for a country to have a robust economy so that it can deal with a crisis, this says nothing about where and what he cut – which did have an impact on pandemic preparedness. Public health was the preserve of local government which was subject to some of the most significant (and still easiest to conceal) cuts during the coalition government. Today Cameron argued to the inquiry that it made sense, because local government has responsibility for so many areas that directly impact health, including housing.

His central argument was that the UK prepared for the wrong kind of pandemic, focusing on a flu outbreak rather than other diseases

Even on health spending, which was relatively well protected, Cameron had to explain why his former health secretary Jeremy Hunt had said in his witness statement that he was worried about capacity and workforce in the NHS. His response was largely that Hunt was a brilliant minister who had campaigned well for more money for his policy area – you could almost hear what he wasn’t saying, which is that you’d expect that from every minister – but that decisions were taken collectively.

Beyond the money, his central argument was that the UK prepared for the wrong kind of pandemic, focusing on a flu outbreak rather than other diseases which had high asymptomatic transmissibility. He also told the inquiry he couldn’t recall being asked to approve any surge capacity for personal protective equipment (PPE), for instance, because this wasn’t something that at the time was considered necessary. This, handily, was down to ‘groupthink’ rather than a decision by one individual, which meant Cameron could talk about the structures he had put in place to deal with serious threats to the country, rather than any particular mistakes he had personally made. ‘You need to have teams going in to question these assumptions,’ he said.

The spending cuts and groupthink points have more in common than might first appear. Cameron rightly pointed out that not enough attention was paid to other diseases and that this was a mistake. What has also transpired from the pandemic is that there were some areas, like public health, that didn’t have enough attention paid to them and which were therefore easier to neglect.

Comments