Sixty-eight days out from the next Scottish Parliament election might seem an ill-advised time to change the leader of Scottish Labour. This morning, Glasgow MSP Anas Sarwar was unveiled as the winner of a low-key internal election, defeating Labour’s Holyrood health spokeswoman Monica Lennon by 58 per cent to 42 per cent. The leadership was spilled after the abrupt ‘resignation’ in January of left-winger Richard Leonard following three forgettable years of drift and decline. Labour last won a Westminster election in Scotland in 2010 and a Holyrood one in 2007; in the 2019 European Parliament elections, it came fifth and just 1.1 per cent away from finishing behind the Greens. The polls do not suggest much cheer is on the way on 6 May.

In the wake of Leonard’s departure, I argued that Sarwar was best placed to take the party forward. He is relatively young (37), a practised media performer, rooted in Glasgow politics, and is one of the few opposition MSPs able to make SNP ministers squirm in the Holyrood chamber. Crucially, he understands that Nicola Sturgeon’s real Achilles heel is not education — though she has a sin to answer for that — but health, since she has been responsible for Scotland’s NHS, either as health minister or first minister, for 11 of the SNP’s 14 years in power.

While he has some way to go to pose any kind of electoral threat to the Nationalists, he is the leadership contender the Scottish Tories most feared. They suspect he can recover traditional Labour voters snatched by the soon-to-depart Ruth Davidson and peel away some moderate Conservatives in the process. With Sarwar as Labour leader, Tory insiders calculate, there will no longer be just one party taking the fight to the SNP. Sarwar can also pummel away merrily at both governments, whereas Scottish Conservative leader Douglas Ross, though he has shown himself to be his own man, will always have to pick his battles.

Sarwar’s victory speech emphasised reviving his party and regaining the trust of Scottish voters, telling them ‘you haven’t had the Scottish Labour Party you deserve’. His address stressed moving on from ‘Yes or No, Leave or Remain’ and a renewed focus on health, education, jobs and social justice, and no wonder: a sizeable minority of Scottish Labour supporters have drifted over to the pro-independence column.

Sarwar’s victory suggests that, after more than a decade of irrelevance, Scottish Labour is finally interested in getting back into the politics business

Sarwar is in an invidious position in that he has to convince pro-Union voters that he isn’t soft on nationalism without pushing away those Labour and Labour-curious electors who have gone soft on it themselves. There is a danger that he repeats the mistakes of Leonard and another predecessor, Kezia Dugdale, and attempts initially to play down the independence question, gains nothing from it, then has to bang on about the Union a few years down the line to shore up his pro-Union support. Everything in the recent history of the Scottish Labour Party tells me he will fall into the same trap but he does have the skills to avoid it.

Sarwar’s election supplies an opportunity for Scottish Labour to regroup, reorganise and reintroduce social democratic priorities to Holyrood, which has been an indolent Nationalist debating society for much of the last decade. The SNP’s mishandling of the pandemic, health, education, drugs, inequality and the economy are areas ripe for a strong Labour challenge. Ideologically, Sarwar falls somewhere between the soft-left and the centrist tradition within Labour and this makes him well-placed to pursue left-of-centre values in a way that is practical and not off-putting to middle-ground voters.

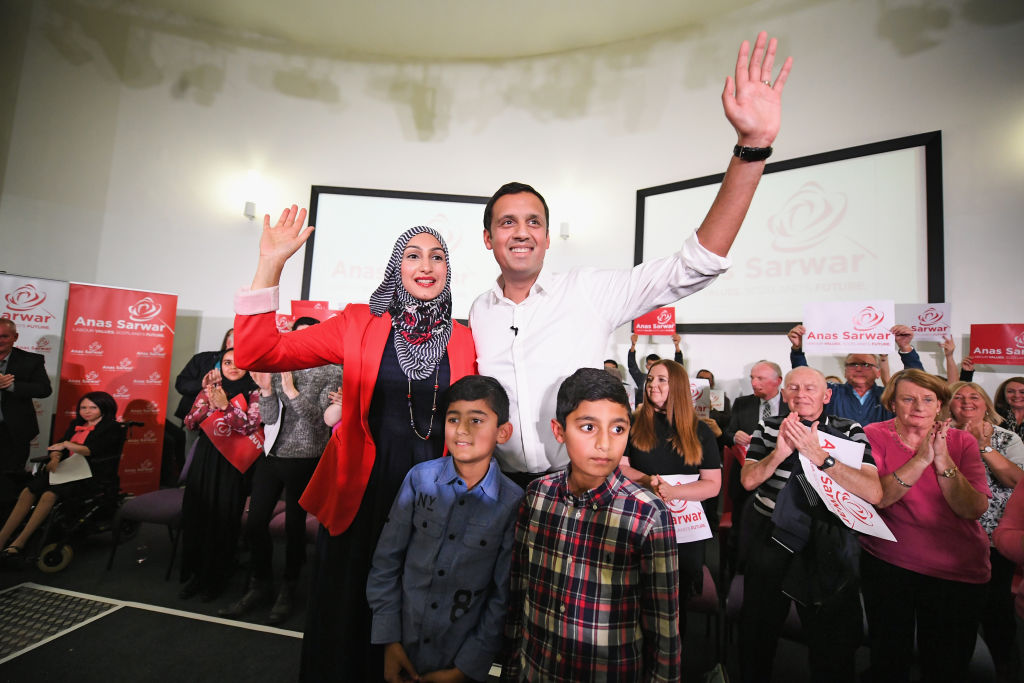

His victory also carries symbolic import. He described himself as ‘the first ever ethnic minority leader of a political party in the UK’. That is not strictly true. Benjamin Disraeli became Tory leader in 1868, Herbert Samuel took charge of the Liberals in 1931, Michael Howard was chosen as Conservative chief in 2003, and Ed Miliband was elected Labour leader in 2010. Nonetheless, Sarwar’s triumph is still a political moment for Scottish and British Muslims and Scots and Brits of Asian descent.

Sarwar belongs to a burgeoning political dynasty. His father, Pakistan-born Chaudhry Mohammad Sarwar, became the UK’s first Muslim MP in 1997 when he was elected for Glasgow Central, a constituency he represented for the next 13 years. Sarwar the elder returned to Pakistan and became first a senator for and later governor of Punjab. His son succeeded him in Glasgow Central in 2010 and the following year became deputy leader of Scottish Labour. He lost his Commons seat in the 2015 SNP landslide but won a Glasgow list seat at Holyrood in 2016.

Despite his father’s political pedigree, Sarwar has previously said: ‘I actually get my politics and values from my mother.’ Perveen used her savings to start up the family’s successful cash-and-carry business and is a political activist in her own right, taking her son to visit Gaza in the early Nineties. There exists a photograph of an 11-year-old Sarwar, kitted out in an oversized blazer and tie, next to a smiling older man in khaki fatigues and a keffiyeh. The young Sarwar looks nonplussed by the proceedings, as any schoolboy might while having his picture taken with Yasser Arafat.

The schoolboy grew up to be a passionate champion of the Palestinians and one who played a valuable, if unacknowledged role, in the Labour antisemitism scandal. While Labour antisemites and their apologists were casting themselves as mere sympathisers with the Palestinians, victims of a Zionist smear campaign, Sarwar was calling antisemitism ‘a cancer and a stain on our society’, demanding the adoption of the full IHRA definition and insisting there was ‘no contradiction between the IHRA definition and the ability to say that Benjamin Netanyahu is a odious individual who is a stain on international peace [or] saying that the actions of the Israeli government go against several UN resolutions and are inhumane, unjust and completely and utterly despicable’. He also said it was ‘not appropriate for the actions of the Israeli government to be used as a way of discriminating against the Jewish community more widely’.

At a time when much more senior Labour figures abdicated leadership, Sarwar stepped up and said that Labour’s antisemitism quagmire was about anti-Jewish bigotry, not pro-Palestinian politics — and demonstrated that there was no inconsistency between support for the Palestinians and enmity towards antisemitism.

This is worth noting because Sarwar did not speak out in a vacuum or without consequence. The Sarwar who put his head above the parapet for Jews is a man who has himself been the target of racism and death threats. During the bilious 2015 election campaign in Scotland, which came in the wake of the No side’s victory in the independence referendum, a man left a voicemail on Sarwar’s constituency office phone line telling him ‘you sell your soul for a bit of money’ and warning him: ‘I’ll come down with a f***ing bullet and put it in you’.

When he stood for the Scottish Labour leadership in 2017, he says, a Labour councillor told him Scotland wasn’t ready to vote for a ‘Paki’. In 2018, Police Scotland launched eight separate investigations into threats against Sarwar, his family and staff. One threat described how his constituency office would be burned down while he and his researchers were inside. He was eventually issued a panic button with a tracking device.

Acknowledging Sarwar as the first person of Asian heritage and the first Muslim to lead a major political party in the UK is about more than the understandable pride many in those communities will feel about his achievement. It is a recognition of what Sarwar has overcome to arrive at this day and proof of the progress that has been made.

Sarwar’s victory suggests that, after more than a decade of irrelevance, Scottish Labour is finally interested in getting back into the politics business. It’s for Sarwar to decide what to do with this mandate, but there are four key points he needs to hit. One, he should take a firm stance for the Union and against a second independence referendum in the lifetime of the next Scottish Parliament. Move hard, move fast, move on. Two, he should review Scottish Labour policy and offer Scots a pragmatic, social democratic vision of a fairer Scotland where opportunities are spread more widely. Three, he should go beyond the tired, established routes of entry into Labour politics (students, activists, trade unions, special advisers) and recruit the best and brightest from Scottish society who share Labour’s values, even and especially if they don’t realise it yet. Four, he needs to knock Labour’s strategy and communications operations into shape. The party has been outgunned by the SNP — in talent, money and imagination — for too long and Sarwar should impress upon the UK party just how starved of resources Scottish Labour is.

Scottish Labour finally has a chance again. The test for Anas Sarwar and his leadership is not what happens on 6 May but what he does with the five years that follow it.

Comments