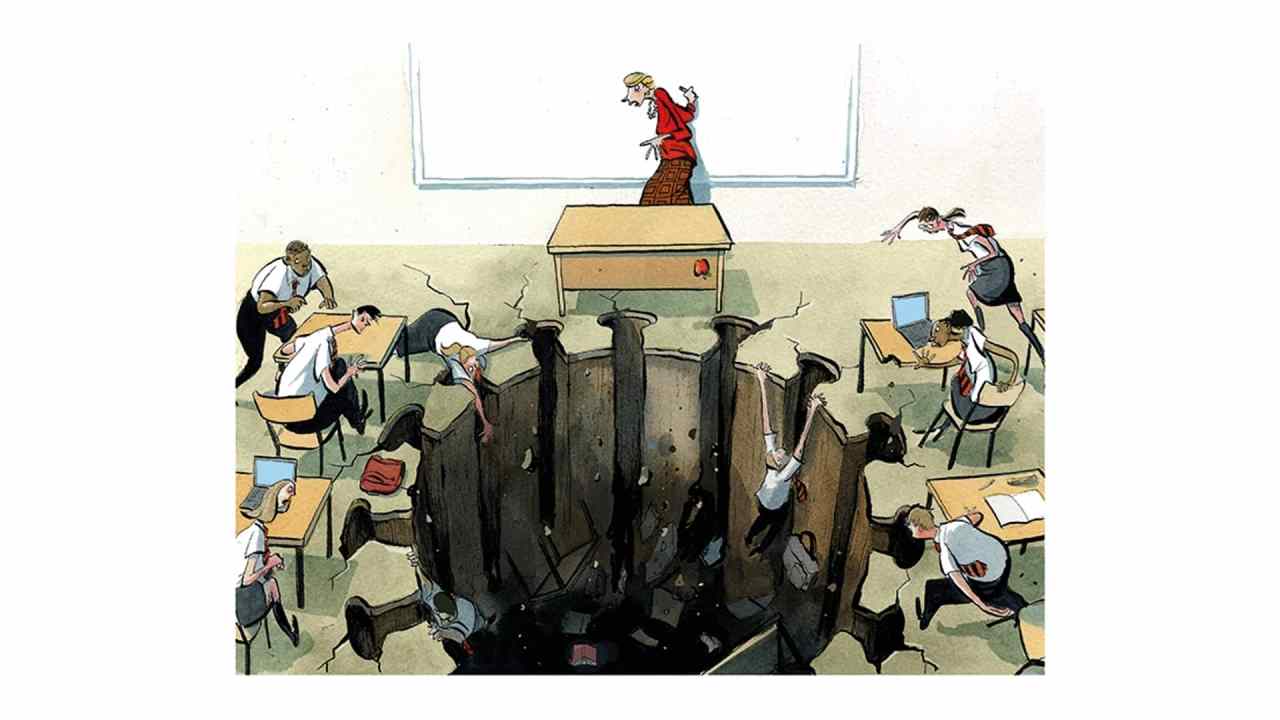

Helping children catch up on the best part of a year out of the classroom is one of the biggest tasks facing the government. On Wednesday, Gavin Williamson announced an extra £400 million in funding which schools can use to run summer programmes and other catch-up projects. That’s on top of £300 million allocated last month and £1 billion announced last year.

Ministers hope that their Recovery Premium will help schools support particularly disadvantaged pupils, who have fallen further behind than their peers as a result of having to do remote learning for so long. But they are also under pressure to show that they are thinking about the long-term, as even the best summer schools will not repair the damage to learning, confidence and other skills caused by the pandemic. At Prime Minister’s Questions, Boris Johnson had a rather bad-tempered exchange with Wes Streeting about this. The Prime Minister told the Labour MP that he was ‘wrong’ about the amount of funding being allocated, but added:

Yes, we will have to do more, because this is the biggest challenge our country faces. We will get it done. We are able to do it because we have been running a strong economy. We had the resources to do it because we had not followed the bankrupt politics of the honorable gentleman and the Labour party.

What could Johnson mean when he says ‘we have to do more’? His own MPs are hoping that he has in mind something along the lines of the ten year plan that was agreed for the NHS. The Prime Minister has made noises to that effect, acknowledging that there needs to be a long-term plan. As part of Wednesday’s announcement, the Education Secretary said that ‘longer-term support over the length of this parliament will be vital to ensure children make up for lost learning’, and said the government’s education recovery commissioner, Sir Kevan Collins, would be working on this over the coming months.

For it to succeed, the recovery plan will need to ensure it does not overlook those children on the very edge of the educational system who were already being excluded and suspended before the pandemic and who have had a year of barely any engagement with teaching at all. These children are regularly forgotten in Westminster discussions about education policy but will need a herculean effort to give them a chance of improving.

That is just one aspect of the challenge facing ministers. Another is that politics moves on remarkably quickly from problems which seem enormous. It will be very easy for Williamson — or his successor in any reshuffle — to lose focus once Britain starts emerging from the pandemic. Whoever is leading the Department for Education needs all the political capital they can muster in order to force the Treasury to keep spending the sums needed on this project for many years to come.

Comments