The great Pixar animated film ‘Monsters, Inc.’ tells the story of Sulley, a fluffy-haired, broad-shouldered and rather cuddly monster who creates energy by scaring children in their beds but then discovers that vastly more energy can be generated by making them laugh instead.

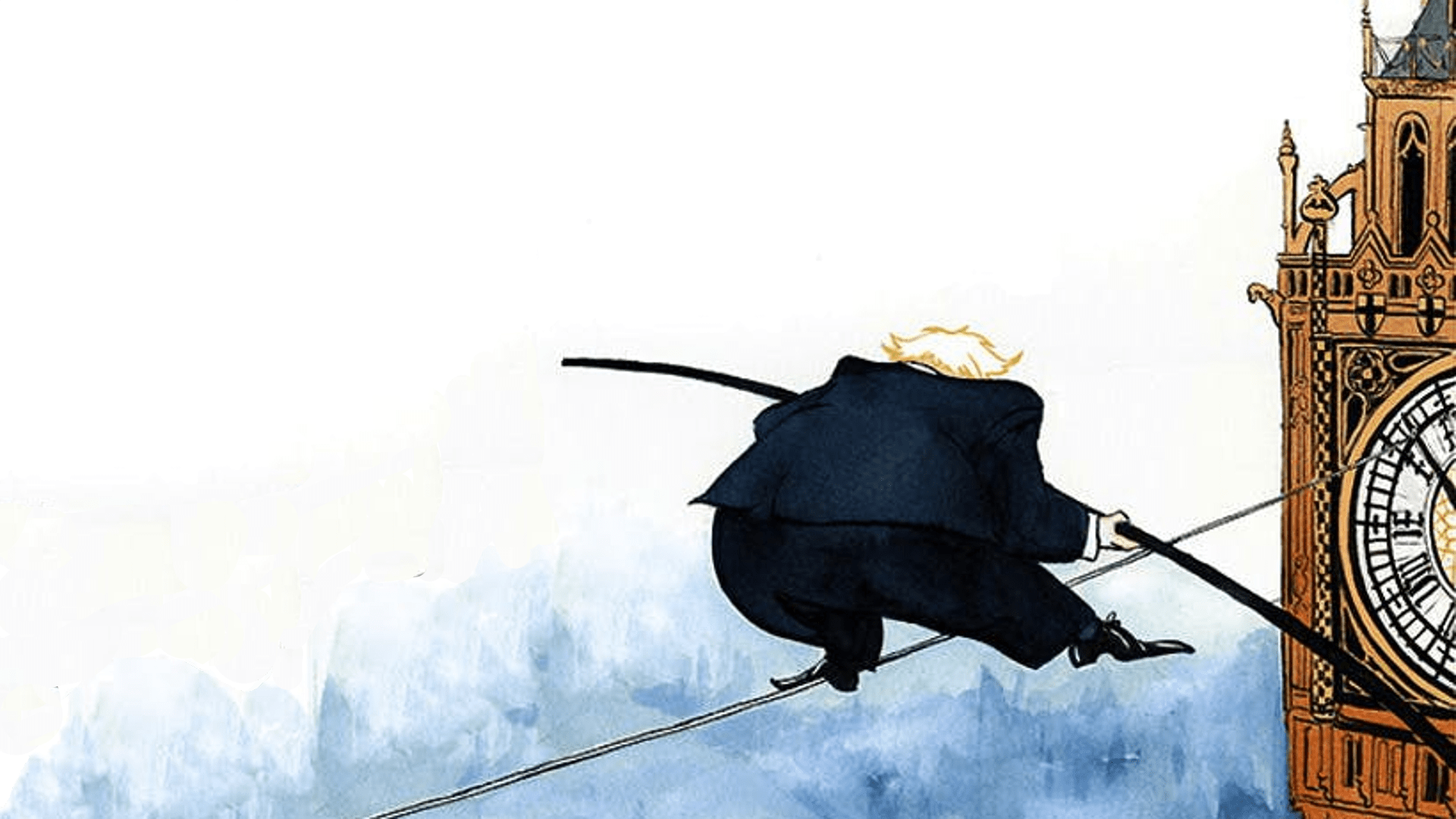

I offer this not as a rival to Boris Johnson’s new plan to make wind energy power the whole of Britain by ‘harvesting the gusts’, but because it has lately seemed to many observers that the Prime Minister has been on a reverse journey to that undertaken by Sulley.

The tousled, broad-shouldered Boris started his Tory leadership generating political energy by means of cheering us all up but then found his administration relying on tactics every bit as chilling as those used on the scare floors of Monsters Incorporated: Stay home, save lives; hands, face, space; Rule of Six; Curfews; Lockdowns; Don’t kill granny.

In his party conference speech today, Boris was at pains to tell us this is just a temporary phase and that he yearns for and will have delivered by this time next year the full return of ‘our pubs, our clubs, our football, our theatre and all the gossipy gregariousness and love of human contact that drives the creativity of our economy’. Furthermore, ‘flying in a plane will be back to normal and hairdressers will no longer look as though they are handling radioactive isotopes’.

Vintage Boris, you might think. But politics is seldom that simple. All governments are sustained by coalitions of voters whose rival interests form ingredients in a recipe that must ideally be combined in a way that produces a result appetising to all.

It is often remarked that Keir Starmer faces a desperate struggle to create an overall offer that both the urban liberal-Left and socially conservative working-class communities will buy into. But new research released by Tory pollster Lord Ashcroft this week shows that in some respects Johnson is also trying to blend chalk and cheese.

Whereas Labour voters overwhelmingly take a cautious, pro-lockdown approach to Covid, agreeing by 65 to 15 per cent that the risk of under-reacting to the disease is more of a threat than over-reacting to it, Tory voters are much more evenly split, taking that view by just 36 to 31 per cent.

And there is some evidence that the 2019 Labour-to-Tory switchers incline more to Labour’s viewpoint than longer-standing Tory supporters. Some 25 per cent of these new Tories agree that ‘the government handled things so badly that things turned out much worse than they needed to be’, compared to 19 per cent of established Tories.

Half of 2019 Tory voters believe that the Government underreacted to the pandemic in its early stages, but that proportion rises to two-thirds of those who had newly switched from Labour.

So it turns out that the new Tory voters of the Blue Wall are significantly temperamentally more risk averse than the traditional entrepreneurial and Thatcherite element of Tory support, with Ashcroft particularly highlighting the tendency for self-employed people to be more frustrated by the economic impact of ongoing restrictions.

Few administrations have invested so heavily in focus groups and private polls as this one and it would seem from the rest of his speech today that the Prime Minister is acutely aware that the values divide runs across other issues too.

While the Thatcher era saw the rise of a class of Tories who revelled in the description ‘small state, low tax’, Johnson – very much a man for having cake and eating it too – seems to have invented the category of ‘big state, low tax’ Conservative.

This involves talking up the power and responsibility of an ambitious and well-funded state to effect beneficial change – expanding NHS capacity, creating a better-funded system for social care of the elderly, more police on the streets, more one-on-one teaching in schools, more funding per pupil, higher pay for teachers and that enormously expensive green energy drive. The PM even name-checked the mission to ‘build a New Jerusalem’ that he attributed jointly to participants of the second world war coalition government, but most people naturally attach to the post-war Attlee Labour administration. This language will surely go down well in Blue Wall seats.

But he doesn’t want higher taxes to pay for all this or for the public sector even to try and do it all. On the contrary, he described Rishi Sunak’s job-saving schemes as ‘things that no Conservative chancellor would have wanted to do’ and charged the Chancellor with making the country ‘more competitive, both in tax and regulation’.

‘We must be clear that there comes a moment when the state must stand back and let the private sector get on with it,’ argued Johnson.

One could just about square this circle of a bigger-smaller state via a belief in Reaganite tax cuts that will deliver higher revenues for the public realm even as the public realm makes up a smaller proportion of a larger overall economy.

But delivering Reaganite tax cuts now, when the annual public sector deficit is north of £300bn and the national debt cresting £2 trillion, would surely be akin to shouting ‘twist’ once too often in a game of Pontoon.

Harsher judges than me will accuse the Prime Minister of being over-optimistic. I prefer to think he is seeking to apply the literary genre of magic realism to contemporary politics as a means of delivering ideological rewards for Thatcherite go-getters and steady-Eddie Blue Wall folk at the same time.

Magic Johnson is certainly a more welcome persona than Scare Floor Sulley and if he can ignite some optimistic animal spirits in the business world along the way then so much the better.

Comments