The beginning of the end for Theresa May was when she tried to see if she could pass her Brexit deal with Labour votes. So Boris Johnson will have shifted uncomfortably in his seat on Tuesday night when it became clear that the House of Commons had approved his tier system only because the opposition had abstained. If they had opposed the measure then it would have failed, such was the size of the Conservative revolt — 53 Tories voted against it, the biggest rebellion of his premiership by far.

The worry for the Prime Minister is that this is not the last time he will need to rely on Keir Starmer’s passivity to get his regulations through. The next time parliament votes on these restrictions at the end of January, it is almost certain that, once again, many Tories will refuse to back the measures if they continue to be so strict or to treat counties as a single unit. West Kent MPs are furious that the whole county — the sixth most populous in England — is in Tier 3 because of high infection rates in the Medway towns, despite very low infection rates in their own constituencies. The problem for the government is that if the tier system were operated on a sub-county level this would not only make the rules more confusing but would also risk the accusation that the government was indulging in political favouritism by freeing leafy places from restrictions and keeping urban areas locked up.

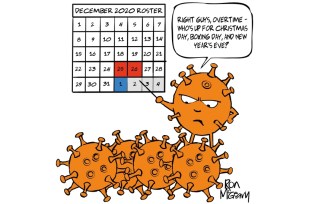

The government has to hope that the tiers vote at the end of January is the last one. By March, the vaccine rollout should have allowed a significant easing of restrictions, with a return to ‘normal’ by April. Johnson’s worry is that the Tory rebellions against his Covid measures keep getting bigger. The original coronavirus act back in March passed without a vote. In September, seven Tories voted against the renewal of those emergency powers; 42 opposed the 10 p.m. curfew in October; and 53 were against the tier system this week.

The consolation for Johnson is that there is now an end in sight to these restrictions. The positive vaccine news of recent weeks — 800,000 doses of the Pfizer vaccine will arrive in the UK in the coming days — means that in the spring he should have a chance to repair relations with his MPs without Covid getting in the way.

But it is a sign of how committed Tory rebels now are to their opposition to the tiers system that the vaccine news has made little difference to their approach. Some ministers hoped that the sense of an end to this era of restrictions would make Tory MPs more patient. There is little sign of that. In part this is because there have been too many promises of an end. It won’t be until the vaccination programme actually starts, which should be as early as next week, that the Tory rebels will begin to consider whether this crisis might really be drawing to a close.

A year into this parliament, the mood is what you would expect during the midterm doldrums

Some Tories think that the vaccine news should change the way the government handles the remaining months of the pandemic. I understand that some departments, including the Cabinet Office, suggested that those university students doing non-laboratory-based courses should study from home in the Easter term. The idea is to avoid a repeat of the spike in infections that was seen when students headed to university in September. The thinking was that, unlike in the autumn, the government can now be confident that these students should be able to have a normal university experience in their summer term, so asking them to study from home for Easter was reasonable. Gavin Williamson, the education secretary, argued against this shift, pointing to the Prime Minister’s desire to prioritise maintaining education during the Covid crisis. But the danger is that the expected post-Christmas increase in infections — over the festive period three households will be able to meet up indoors, a considerable loosening of the current rules — could combine with a spike as students head back to their universities.

So the question is: how lasting is the damage that has been done to Johnson’s relationship with his own MPs? Certainly few would have thought a year ago, when Johnson won his 80-seat majority, that there would be rebellions of this size. We are only a year into this parliament but the mood is what you would expect during the midterm doldrums.

If the Oxford vaccine — of which the UK has sufficient doses on order to vaccinate the whole adult population — is approved by the regulator and the rollout goes smoothly, this could allay the frustration. Indeed, if the final stretch of this crisis is navigated well, it could show the government’s whole effort in handling the virus in a better light and help it to salvage some of its reputation for competence.

Johnson’s relationship with Tory MPs has always been more transactional than ideological. They picked him as leader because they thought, rightly, that he could win an election. There are no philosophical Johnsonians, however. Yet if the PM can rally the Tory coalition next year and the economy rebounds more strongly than expected, the discontent of the last few months will be behind him — though the challenge of dealing with the damage that the virus has done to the public finances and society will not be. But if the rollout of the vaccine is bumpy and tight restrictions have to be maintained for longer than expected, then that discontent will only grow and become more dangerous.

A pandemic was always going to be a nightmare for any Tory prime minister. The public health restrictions, the state delving into the minutiae of family and economic life was always going to be difficult for Conservatives to support. It goes against almost every Tory instinct for the state to dictate whether grandparents can meet their grandchildren, and even to ban church services from taking places.

Once the pandemic is over, Johnson can be confident that he won’t have to deal with another public health emergency like it while he remains in office. But his attempt to repair relations with his party will depend on how quickly he can rally them to him. Prime ministers can’t make a habit of relying on the opposition’s action, or inaction, to get their business through.

spectator.co.uk/shots - Hear daily political analysis from James Forsyth, Katy Balls, Fraser Nelson and more.

Comments