Next time there’s a pandemic, the advice of Dr Jenny Harries will be crucial. She runs the UK Health Security Agency, set up during Covid to replace the much-maligned Public Health England. In her interview with the Telegraph there seemed to be a penny-dropping moment where she suggested that Britain may be more like Sweden next time:

What we saw with Omicron and later waves of the pandemic, and even now, is that people are good at watching the data and they will take action themselves. You can see it in footfall going down. People actually start to manage their own socialisation, and the [viral] waves flatten off and come down.

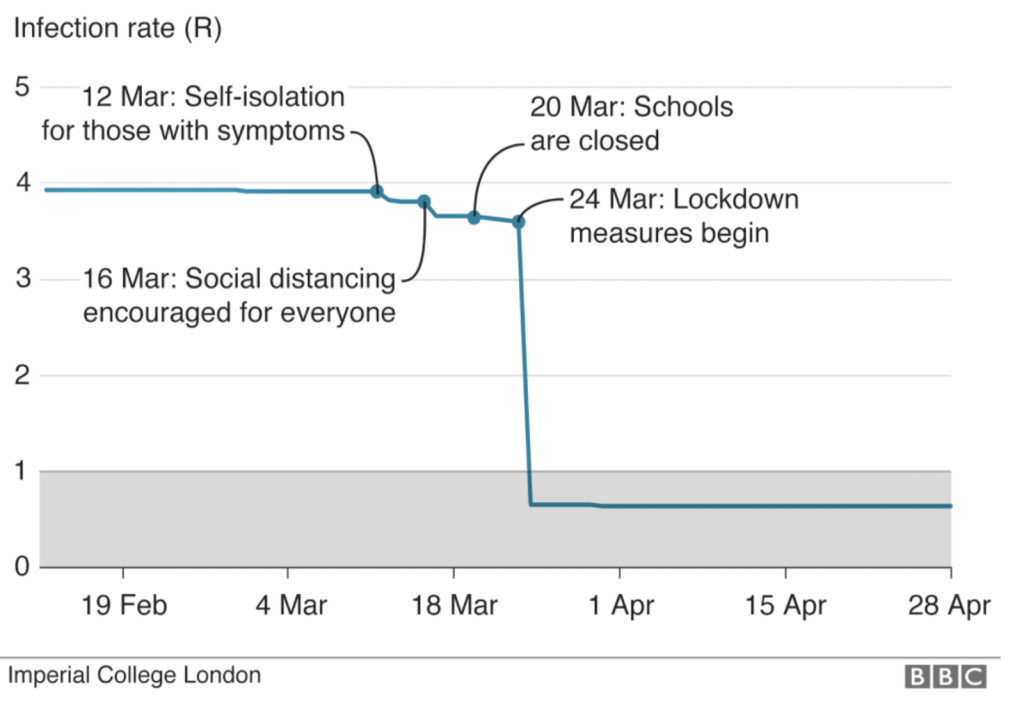

She missed a crucial point here: it wasn’t just after Omicron. Brits locked themselves down from the offset, in wave one, long before lockdown was needlessly imposed – a common-sense solution. And something that the modellers failed to take into account. This crucial, demonstrable fact disproves lockdown theory, hastily assembled by Professor Neil Ferguson and exported – to disastrous effect – worldwide. The work of Ferguson’s group at Imperial took as its assumption the idea that the virus will spread at a constant exponential rate (or R-number) because there would be no serious behavioural response. His other assumption: that such a response can only be achieved by police orders and state mandates. The non-pharmaceutical interventions, or NPIs.

This was lockdown theory, one of the most consequential ideas every to come from an academic.

a) No serious organic behavioural response from the population. So the R-number (rate of exponential viral growth) stays constant.

b) This r-number can be nudged down by government steps (mandated self-isolation, school closures) but this makes only a small difference. It doesn’t stop the exponential growth

c) Lockdown is the magic bullet. As soon as it is imposed, the R-number collapses overnight to below one so the virus is forced into retreat. This is the cliff-edge theory: lockdown will see Covid infection numbers fall off a cliff.

This lockdown theory, so often presented as fact, was neatly expressed in a graph, below:-

Imperial drew similar graphs for countries world over and calculated how many dead there would be if countries didn’t lock down. Figures of 85,000 for wave one were produced for Sweden which never locked down and ended up with just under 25,000 deaths over two years of Covid. Rather than ask why it got Sweden wrong – and what the implications were for the rest of its analysis – Imperial denied ever coming up with the 85,000 figure. It even had The Times print the following correction.

“We have been asked to make clear that Imperial College made no prediction for Sweden and the figure was a projection by Swedish scientists referencing Imperial’s modelling for other countries.“

This matters because it shows how Imperial itself was the business of trail-covering and false denial, rather than asking why its original calculation had been so wrong and what lessons could be learned by Prof Ferguson and whoever peer-reviewed his work.

So: why was Ferguson so wrong about Sweden? Why did the graphs spat out by Sage – which almost had us locked down a third time – end up being such nonsense? Because they didn’t factor in the behavioural response: that, in a high-information democracy, people would keep track of the news and take their own evasive action. Prof. Graham Medley, chair of Sage modellers, later admitted :-

“Rather than try to second-guess what people are going to do, we tend to presume that people will carry on doing what they are going to do. And decision makers will have to include that uncertainty.”

Come again? Where did they admit that? ‘Decision makers’ were never told that Sage models were based on the obviously-screamingly-wrong assumption that “people will carry on doing what they are doing”. This assumption was so wrong as to render the Sage charts obvious nonsense. No one was told this assumption at the time, raising obvious transparency and ethical issues about the use of models in public policy.

It has been argued that the obedient and sensible Swedes did so, but Brits are more unruly. This can easily be disproved by mobile phone data, via Google Mobility data, which gives unprecedented detail on who went where. It shows the UK behavioural response was actually sharper than Sweden’s before the first lockdown.

In fact, academic studies drawing on actual (rather than Imperial’s imagined) figures suggest Covid had actually been forced into reverse before the first lockdown was imposed.

All this really is quite important and Dr Harries cannot in all good faith suggest that the British only started responding quickly after Omicron. It’s possible – even likely – that her colleagues were not tracking Google mobility data during the first wave and simply not know how quickly Brits had locked down. But the data is now there for all to see.

This should be the single most important fact in any pandemic response. We now know, from observed data, that people lock themselves down and can do so in such numbers as to force a virus into reverse. But Dr Harries is a serious woman: why would she speak of an organic behavioural response after Omicron and not before other waves? Perhaps because doing so would admit that the Sage graphs that kept Britain locked down for so much of 2021 were based on a false premise. The minister responsible for the UKHSA is Neil O’Brien, who devoted much of his time to hounding academics and others who questioned lockdown theory.

Perhaps Dr Harries waiting for the inquiry to point this out. If so, this delay is actively dangerous: a new pathogen could emerge any moment and now is the time to be asking questions. We are living in the quiet between the viral storms, and need to use this period well. Speaking honestly about what happened in March 2020 is vital: there really is no time to lose.

Comments