As the UK – and indeed the world – faces the prospect of an economic downturn this year, what exactly can the government do about it? This remains an ongoing debate within the Tory party, as Rishi Sunak continues to emphasise the importance of stability, while Liz Truss’s most loyal supporters keep pressuring the government to revive her focus on economic growth.

This morning a trio of cabinet members showed up in the City to suggest that it doesn’t have to be one or the other. Culture Secretary Michelle Donelan, Business Secretary Grant Shapps and the main act, Chancellor Jeremy Hunt, opened this morning’s conference at Bloomberg by insisting the UK has all the resources it needs to see its digital and tech sectors thrive. They want to boost economic growth and, crucially, not spend lots of taxpayer money.

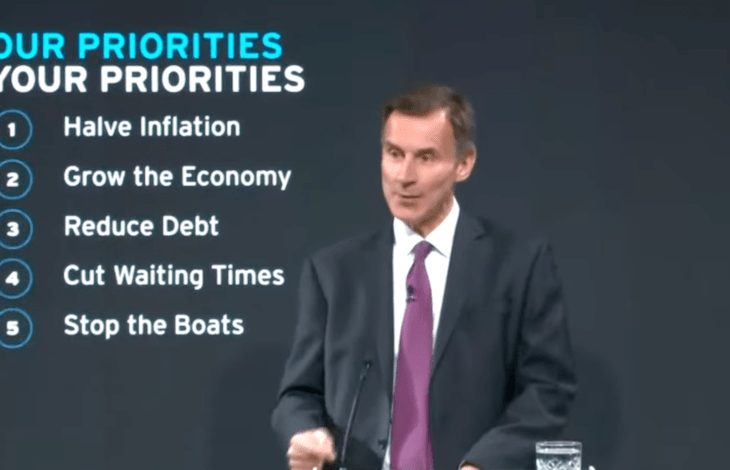

Just as we got the Prime Minister’s five pledges at the start of the year, today we heard the Chancellor’s four pillars: Enterprise, education, employment and everywhere. In his keynote speech, Hunt explained what he’s calling the ‘“four Es” of economic growth’, which include removing barriers to innovation, up-skilling the workforce, getting the economically inactive back to into employment and making sure these things happen across the UK – not just in the richer parts of the country.

His speech was largely an ode to British business, with references to fintech start-ups, green energy development and Formula One Grand Prix manufacturing. It also served to bolster his government’s Brexit credentials: ‘Our plan for growth,’ he said, ‘is made possible by Brexit.’ But there were no new public policy announcements. Rather, Hunt served up a reminder of what’s already been pledged (the ‘Edinburgh reforms’ from last month that will start to liberalise the City post-Brexit), as well as hints of what might still be to come.

Hunt’s emphasis on employment was largely focused on the economically inactive: with 6.6 million working-age people out of work, he emphasised the importance of helping them back into the workforce. ‘The pandemic has exposed weaknesses in our model,’ he told the audience. ‘Total employment is nearly 300,000 people lower than pre-pandemic, with around one fifth of working-age adults economically inactive.’

This is the first admission we’d had from Hunt that the current welfare system needs reforming. This was an issue flagged by The Spectator last year as it discovered that more than 5 million people are receiving out-of-work benefits post-furlough, despite a near record high of 1.1 million vacancies across the labour market.

If Hunt’s ‘four Es’ sound a lot like Sunak’s Mais lecture from last February, it’s because they were inspired by it. Hunt is expanding on Sunak’s vision to create Britain’s own Silicon Valley, made possible long-term by life-long learning and a more nimble, flexible regulatory environment. It’s the legacy we know Sunak wants to craft for himself, regardless of what else happens during his tenure. Today, Hunt suggested he is not only on board, but devoting his efforts to the same policy goals.

But what about the short-term? Hunt knows that his attack on ‘declinism’ today comes at a difficult time, when his Treasury’s plan to get the public finances back in order means more tough decisions to come. Hunt described his speech today as the ‘framework against which individual policies will be assessed and taken forward’ – but we are not expecting many of those policy announcements anytime soon. Indeed, his Spring Budget is expected to be a slimmed down event: no new tax hikes, but no major tax cuts, either.

This will cast doubt for some listening to his speech today, as he insists his government’s ‘ambition should be to have nothing less than the most competitive tax regime of any major country’. Yet he and the Prime Minister have so far made a habit of raising tax again and again. They would point out that such decisions were necessary to recover from last year’s mini-Budget fiasco: within days of Sunak and Hunt arriving in Downing Street, the spike in borrowing costs was recovering. But what about the legacy of the Conservative governments that came before? After more than a decade of Tory rule, the tax burden sits at a 72-year high.

We know from Hunt’s leadership campaign last year that if he had his way, corporation tax would be closer to 15 per cent, rather than climbing to 25 per cent for the UK’s biggest business. But tax cuts are still expected to be some way off. The Chancellor emphasised in his speech that the priority remained tackling inflation, repeating Sunak’s pledge to halve it this year. It’s a promise that has always been – and remains – largely out of the government's control.

The gamble for Hunt today, then, is whether his optimism can counter not just those who are nervous about the UK’s long-term prospects, but those who are nervous about what the next few months have in store.

Comments