It was the chronicle of a death foretold. Last year Keir Starmer’s chief of staff, Morgan McSweeney, drafted a memo for his boss spelling out in the starkest terms How Labour Could Fail. This week, instead of celebrating the first anniversary of Labour’s landslide election victory, the two men revisited that analysis and reflected on its prescience. McSweeney may be in the firing line of Labour backbenchers angry at Downing Street’s mishandling of welfare reform, but he was eerily accurate in predicting the problems that this administration would face.

‘The only task Labour finds harder than taking power from the Conservatives is keeping it,’ McSweeney warned. ‘Few Labour prime ministers have ever secured two full successive terms… Today, swing voters are more volatile, less attached to any party and more willing to rapidly switch allegiance than ever before… A big majority is no guarantee of victory at the subsequent election.’

McSweeney’s view was (and remains) that this is as much a commentary on Labour as it is on Britain. ‘When the Tories win power they always do so with the aim of retaining it,’ the memo goes on. ‘The decisions they take are always oriented towards winning the next election. When Labour wins, we seek to change the world.’

Labour’s task, outlined in the document, was to ‘define the mandate’ Starmer was about to win, which meant ‘sorting out the NHS’, ‘stopping the boats’ and ‘improving living standards’. It meant showing voters that Starmer had ‘changed the party so he could change the country’ and being able to ‘define a villain’. McSweeney wrote: ‘We must approach every action in government with clarity about who is the villain: who is responsible for getting us into this situation? And how are we taking them on to turn things around?’ It meant convincing people that ‘Keir is making Britain “respected abroad” again.’

McSweeney predicted what might derail this mission: ‘On our own side, there will be pressure to adopt causes that are popular with our own supporters and to lose focus on the electorate. There will be hundreds of MPs with rather a lot of time on their hands who may start to behave like super activists or campaigners, rather than parliamentarians.’ In a week when the PM capitulated in the face of backbench fury over welfare reform, it is little wonder that he and his close aides revisited the memo to try to plot a way to get back on track.

Any audit of Labour’s first year must note that the NHS is only slowly getting sorted, that the boats have increased in number and that living standards remain depressed. Starmer’s inability to change his party’s habit of self-indulgence is one of the biggest obstacles to him changing the country. By failing to tell the public clearly what he is about, Starmer has too often allowed Labour to be defined as the villains.

‘Chapter one is Sue. Chapter two is Morgan takes over. Chapter three is things fall apart’

His first mistake was to appoint Sue Gray as his chief of staff. ‘Chapter one is Sue,’ says a senior Labour figure close to Downing Street. ‘Chapter two is Morgan takes over. Chapter three is things fall apart.’

Hired to prepare for government, Gray appointed her own allies and marginalised experienced political aides. Huge red files of information on the problems each department would face and how they might deal with them were ignored. When Starmer entered government, ministers realised with horror that there was no plan for the crucial first 100 days.

Starmer, who was director of public prosecutions during the London riots of 2011, reacted confidently to violence on the streets over the summer, but any political credit for that was swept away by stories about the freebies he took as leader of the opposition, including expensive spectacles, tickets for a box at Arsenal, and £5,000 of clothes for his wife Victoria. At his very first cabinet meeting, the Saturday after polling day, Starmer invited Laurie Magnus, the head of ethics, to address ministers. He looked like a hypocrite. The cabinet minister said: ‘Sue should carry the can for the clothes. She didn’t see it as a problem beforehand and she imagined it would all blow over.’ It didn’t. By October, Gray was gone and McSweeney was chief of staff.

The government’s next misstep was Rachel Reeves’s announcement that the winter fuel allowance would be cut for all but the poorest pensioners, a decision attributed to her being spooked by the state of the public finances. ‘The inheritance was significantly worse than we were told,’ a Treasury official said. ‘It’s pretty scary when the debt management office says things might fall over.’

The universal winter fuel allowance was something the Treasury had been trying to abolish for years, but every chancellor since Gordon Brown had rejected that on political grounds. When James Forsyth, who left The Spectator to work for Rishi Sunak, bumped into an ally of McSweeney in St James’s Park, he said: ‘All the time I was in No. 10, the Treasury tried to get winter fuel through, and every time I said no.’

‘Rachel is a study in Shakespearean tragedy,’ a cabinet colleague of hers remarks. ‘She played a big part in getting our economic credibility back. But in opposition she essentially said no to things, and the problem is that the first thing she said yes to in government was the winter fuel cut.’ Starmer and Reeves both began with a miserablist message that ‘things will get worse before they get better’. This resulted from a major misunderstanding. ‘We tried to do what Cameron and Osborne did in 2010 and blame the last government,’ the cabinet minister says. ‘And while things were significantly worse than we expected, that didn’t resonate with the public.’ A Labour strategist adds: ‘We assumed it was 2010 because the public finances were a mess, but the public appetite was for 1997. They wanted the hopey-changey thing. We told them how it would get worse. We still haven’t really explained how it will get better. It’s almost like what we liked about George Osborne’s “pain for a purpose” was the pain part.’

Reeves began by saying growth was her top priority, but to balance the books she imposed a huge tax rise on business, which had the opposite effect. Then, when gilt markets panicked in January and Donald Trump’s tariffs made matters worse in February, the long-planned reform of welfare was diverted into a simple money-saving exercise.

The recent humiliation on welfare led to a circular firing squad, where the centre has briefed against the veteran chief whip Alan Campbell. ‘Alan warned them nine months ago that they might lose the bill,’ a friend of Campbell says, ‘and they threatened to sack him a week ago.’

McSweeney can’t have been that surprised by the rebellion, since his 2024 memo warned: ‘We need to make sure that we deliver on the causes that are most precious to our members and supporters… The three issues that are most salient for our base are child poverty, climate breakdown, and services and benefits for society’s most vulnerable. We should make sure that vulnerable groups are systematically examined in the audits of public services.’

The Chancellor is understandably bruised, and she was tearful at PMQs when Starmer refused to confirm she would keep her job. In private, ministers say she seems ‘exasperated’ and ‘completely worn out’, challenging her cabinet critics to say what they would do differently. ‘She’s lost confidence,’ another minister says. ‘She makes her argument in a very defensive way: “What’s the alternative?”’

Amid the chaos, two other political crises seem to have been averted. The re-engagement with the EU has not led to the major public row McSweeney and Starmer expected; and, on tariffs, the strategy of fighting battles with Trump in private rather than parading disapproval in public has paid off. ‘Both were areas which were well prepared in opposition,’ a minister notes.

‘We assumed it was 2010 because the public finances were a mess, but the public appetite was for 1997’

It is hard to overstate what strange bedfellows Starmer and Trump are. Anthony Scaramucci, Trump’s former director of communications, told the Chalke Valley history festival last Thursday that Trump complained to him that he could not access porn on White House computers; Starmer, meanwhile, connects with the thrice-married President ‘by talking about their families’, an aide explains. Even this can be a minefield. Halfway through their White House lunch, a few weeks after the Prime Minister’s brother had died of cancer, Trump turned to him and probed: ‘Your brother, Keir… He died… Was it a good death?’ Starmer kept his sangfroid in the face of the sheer weirdness of the conversation and steered it back to lowering tariffs for Jaguar Land Rover.

Trump, Starmer’s team concluded, is genuinely ‘obsessed with death’ – his own and other people’s. But if Trump believes God spared him from assassination to make America great again, Starmer’s irreducible core seems to be that he was put on earth to deliver modest changes to Britain’s economy and society, downplaying the degree to which Britain is in crisis. ‘He’s Rishi Sunak without the billionaire wife,’ notes one minister.

Starmer and McSweeney both know that unless they can make a material difference to people’s lives, the next election is Nigel Farage’s to lose. It is also the case that without a clearer narrative about the government’s core beliefs, path and destination, the PM will not buy the time to make improvements before voters jump ship.

Tony Blair won a landslide re-election in 2001 with the slogan ‘A lot done, a lot more to do’, but McSweeney doesn’t think that will wash in 2029. He has told colleagues that the cost-of-living crisis people described in 2022 is over but that it has revealed a far deeper ‘prolonged crushing of living standards’. His insight is that ‘the most economically insecure people in this country are people who work in their mid- to late forties’. These are not people who are necessarily poor,

but in families with caring responsibilities for children and elderly relatives, whose mortgages have got relatively more expensive, who have had to reduce the number or quality of holidays they enjoy and have downgraded their BMWs for Hondas. McSweeney’s joke is: ‘I’ve always driven a Honda, so I can never feel loss of status.’

He has also concluded that the machinery of government cannot deliver for these voters. After his first week in the job, McSweeney was telling colleagues that he was shocked at how few civil servants were prepared to take decisions. It was a sign of his poor judgment and caution that, against the advice of the expert panel, the PM appointed as cabinet secretary Sir Chris Wormald, the most plodding time-server of the four mandarins on the shortlist. ‘It was an eccentric appointment,’ a cabinet minister says. ‘If you want to do drastic reform of the state, you don’t appoint someone whose grandfather and father were both civil servants.’

McSweeney is exercised by the fact that the civil service has 7,000 communications officers, 4,500 of whom work for arm’s-length bodies and quangos and frequently attack what the government is trying to do. Like Dominic Cummings, he is enthused by the possibilities of technology to speed change, such as AI in the NHS or gamers being hired by the Ministry of Defence to fly drones. He is now experimenting with ‘synthetic voters’ – essentially fake focus groups of AI voters who can tell ministers more quickly and cheaply what the public thinks of policies. In the last week he has been reading The Technological Republic by Alexander Karp, co-founder of the tech firm Palantir, which argues that the West’s technical dominance over the past century has been down to collaboration between governments and tech firms.

But few ministers are radicals. In the cabinet, only Shabana Mahmood, the Justice Secretary, and Liz Kendall at Work and Pensions regularly make any argument about reducing the things that the state provides. Reeves’s recent ‘zero based review’, analysing everything government paid for, found barely any meaningful savings.

McSweeney told colleagues he was shocked at how few civil servants were prepared to take decisions

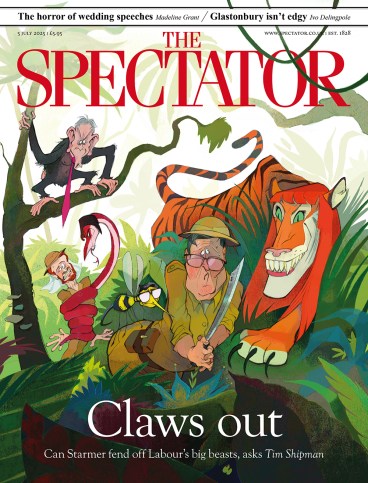

The knives are now out for McSweeney, with ministers demanding ‘regime change’. ‘He’s the best campaigner in the business,’ says one, ‘but you need to create the political project first, and then the campaign serves the project. People like leadership that makes an argument.’

There is the crunch. All governments take their priorities, impulses, strengths and weaknesses from the prime minister. If this government lacks a clear direction, that is not because it has let down Keir Starmer but because it has been created in his image. ‘We are living through an experiment in what happens when you’re in government and you haven’t got politics,’ the minister argues.

In an interview last week with his biographer Tom Baldwin (whom some on the left would like to replace McSweeney), Starmer admitted that he did not properly read his big speech on immigration, in which he warned that Britain might come to resemble ‘an island of strangers’, and neither he nor his speechwriters realised the echoes of that phrase with Enoch Powell’s ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech. He claimed that at the time he had been discombobulated by a fire-bomb attack on his home (an incident which credible figures in government have linked to the Russians, who will be delighted to know it put the PM off his game). He also admitted that he was too busy at the Nato summit to engage with the proposed welfare changes.

‘It was more like an interview a prime minister gives when they leave, not during office,’ a minister says. The more Starmer repeated that he is not interested in having an ‘-ism’ or a bold vision, the more he has seemed to be pushed around by backbenchers, many of whom are convinced they will lose their seats to Reform in 2029.

On Tuesday, Starmer circled the wagons to defend McSweeney, telling cabinet: ‘We will learn from our mistakes, but we will not turn on our staff – including our chief of staff, without whom none of us would be sitting around this cabinet table.’

While some MPs openly discuss removing Starmer, Labour historically has little taste for regicide. Of the other big beasts, Reeves is wounded and may be replaced after the autumn budget; Yvette Cooper, the Home Secretary, has failed to stop the boats; David Lammy, the Foreign Secretary, has a mixed record. Only the Deputy Prime Minister Angela Rayner has solidified her position. Colleagues say she is ‘very quiet’ in cabinet: ‘biding her time’.

The threat from Reform is certainly something else that McSweeney foresaw. The exhumed memo reads: ‘Our next fight will be with a more muscular populist right: it is more likely that the rump of the Tory party merges into Reform than vice-versa … Our job will be to paint them as a … coalition of chaos that cannot be let loose on the public again… Beware the politician with simple ideas.’

But for a battle against a leader with simple ideas, Labour seems to have deployed a leader with no ideas. When the German left did so, in the form of Olaf Scholz, it did not end well. When a Labour strategist met recently with one of Scholz’s advisers, he asked why the SPD leader lost.

The German said: ‘He did not know how to be chancellor, what he wanted to do or the story he wanted to tell. At every moment of crisis, instead of acting in accordance with the German people’s needs and wishes, Olaf Scholz either did not act or did the opposite of what they were instructing him to do.’ Five minutes into the presentation, the Labour man offered him a job.

As McSweeney explained in his memo, if Starmer doesn’t go where the voters are, the voters will go somewhere else.

What would Tim Shipman and Michael Gove say Starmer’s greatest mistake and biggest success are from his first year in office? They join the Spectator’s Edition podcast to discuss further:

Comments