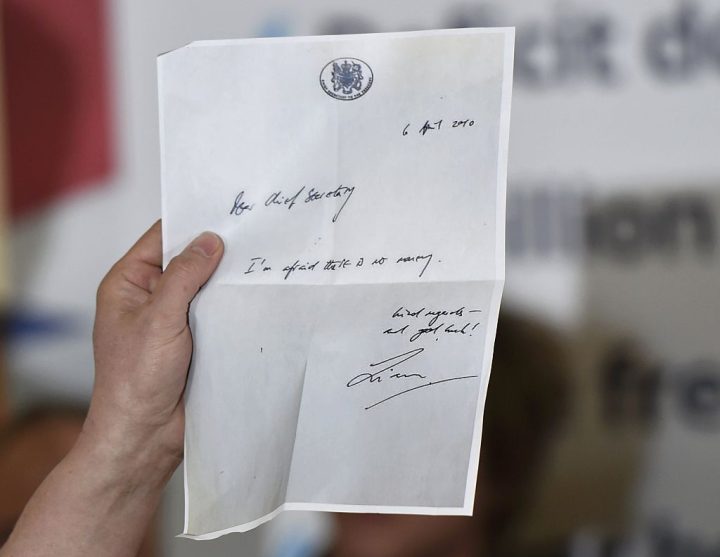

It’s back! The scrap of paper left in 2010 by Labour’s outgoing chief secretary to the Treasury Liam Byrne for his successor, that half-jokily, semi-sympathetically stated ‘I’m afraid there is no money’ is once more in the news.

When the recipient of the note, Liberal Democrat David Laws, made its contents public it was widely taken to confirm the incoming coalition government’s claim that Labour had irresponsibly left the country’s finances in a mess. It was concrete, and apparently irrefutable, evidence of the need for the swingeing austerity later imposed by Chancellor George Osborne. The note also helped Osborne deflect responsibility for austerity onto Labour.

Like King Arthur’s mythical sword Excalibur, it has remained ever ready to be deployed to eviscerate the Labour enemy

It worked. By the time of the 2015 election more voters blamed the opposition for spending cuts than the government itself. Just in case they needed reminding, during that campaign prime minister David Cameron flourished a copy of Byrne’s note at meetings to dramatize his claim that Labour could not be trusted to manage the economy. It was a view with which many Britons agreed, and, on that basis, they returned a majority Conservative government for the first time since 1992.

Since then, however, thanks to Brexit, Covid, the confusions of the Johnson years and the chaos of the Truss weeks, Conservatives stopped referring to Byrne’s note. Like King Arthur’s mythical sword Excalibur, however, it has remained ever ready to be deployed as a magical weapon to, once again, eviscerate the Labour enemy.

Greg Hands is principally responsible for its reappearance. Since becoming Conservative chair in February he has sometimes daily, occasionally hourly, tweeted references to Byrne’s note, meaning it has now likely been seen by millions. Taking her cue from Hands, earlier this week Thérèse Coffey told the Commons the supposed over-spending of the last Labour government was more responsible for the sewage now polluting Britain’s rivers and coasts than anything that happened since 2010. Similarly, Suella Braverman told Good Morning Britain viewers reductions in police numbers over the last decade were the fault of Labour, not Conservative, ministers.

All governing parties seeking re-election – especially those whose record in power is not much to write home about – want to alarm voters about their opponents. Some of these scare tactics have been more legitimate and successful than others. In 1950, Clement Attlee’s Labour warned Winston Churchill would return the country to the mass unemployment of the 1930s and put pictures of Jarrow marchers on posters to make the point. When seeking re-election in 1959, Conservatives mined memories of Labour post-war austerity, contrasting it to the world of plenty then enjoyed by many by pleading: ‘Don’t let Labour ruin it’.

Perhaps the most successful example of this tactic came during the 1980s and 1990s when Conservative campaigns repeatedly disinterred pictures of rubbish piling up on the streets during the 1978/9 winter of discontent. This is what would happen, they said, if voters were daft enough to vote Labour.

By 1997, however, even that warning from history had worn thin. This was partly thanks to Tony Blair’s assertion that Labour was no longer that kind of party, but it was mostly because Black Wednesday had damaged perceptions of the Conservatives’ own competence. Once in office and seeking re-election in 2001, Labour then returned the favour by warning that voting Conservative would mean the ‘return of boom and bust’.

Will the redeployment of Byrne’s note work its magic yet again? Facing brutal and consistent Labour attacks on the manifold failures of thirteen years of Conservative rule, with inflation riding high, strikes aplenty and public services in crisis, you might wonder. Surely, in light of this daily misery voters will be inclined to forget any distant and frankly distorted memories they might have of Labour failure?

Even Blue Wall voters now give Labour the edge over the Conservatives in terms of who they consider best to manage the economy. But don’t ever underestimate the power of the material, the tangible in politics, a world where words and statistics can mean anything and nothing.

Polling suggests Byrne’s scrap of paper still has the ability to make many reflect on Labour’s economic record. Excalibur might be rusty, but it still has a sharp edge to its blade. So don’t be surprised if at a Prime Minister’s Questions closer to the next election Rishi Sunak waves Byrne’s note in Keir Starmer’s face to Tory MPs’ cheers.

Comments