We’ve just celebrated the birth of a refugee who went on to radicalise a group of fishermen and transform the worldview of millions of people. You might not feel comfortable with this depiction of Jesus Christ but it does illustrate the challenges and limitations of language and labelling when dealing with contemporary violent extremism.

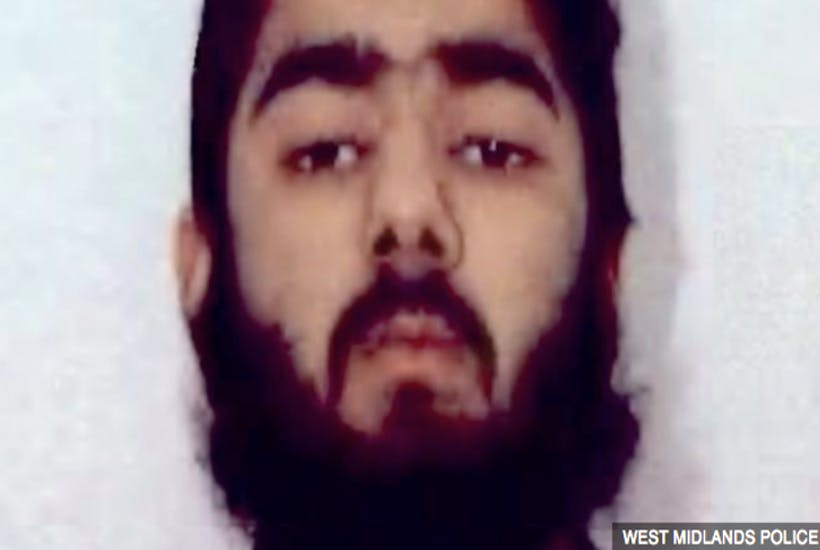

I was on the Today programme on Radio 4 this morning to speak about Healthy Identity Intervention (HII) – a psychosocial approach to changing the mindset of terrorists which was used in prison to treat Usman Khan prior to his murderous rampage on London Bridge. I was asked to comment after the HII programme’s main architect, the forensic Psychologist Christopher Dean, emphasised the limitations of the approach on changing a determined terrorist psyche.

I’ve great respect for the brave men and women who work on the front line of HM Prison and Probation Service delivering these interventions, without much in the way of training and a moral universe away from those they are trying to fix. That said, I raised specific concerns about the effectiveness of HII back in 2016 when I led an independent Government review into the threat posed by Islamist extremists in prison and probation.

Healthy Identity Intervention is a generic approach which is unlikely to cut much ice with offenders who think they have divine permission to annihilate themselves and other citizens. Moreover, the notion that a terrorist offender serving a lengthy sentence in our badly stretched and disordered prison system can maintain a ‘healthy’ mindset while in custody, is asking an awful lot from a handful of one-to-one counselling sessions.

From practical experience, interventions that seek to address the offender as an individual with his own unique set of pathologies that drove him into violent extremism are more likely to reduce their dangerousness in custody and upon release. Terrorist offenders do not emerge out of thin air, but they are also frustratingly difficult to categorise in terms of common denominators. In this country we have been menaced by petty thugs, engineers and medical doctors. Each has descended into extremism in different ways at different speeds, often helped or hindered by diverse factors associated with their background and early life. Understanding what role those ‘precursors’ played provides clues as to whether an offender needs a theological or psychological, clinical or social intervention, and in what combination. That process takes a long time and is likely to be most effective where trust has been established. It goes without saying it will also be very expensive.

Individualised treatment plans would be more effective if a single specialised team followed the extremist from their first night in custody to their last night on licence in the community – a process that is still hopelessly fractured and dependent on clunky inter-agency protocols. I suggested this approach in 2016, arguing that the police, prison and security services should assertively manage every aspect of a terrorist’s journey through the criminal justice system as equal partners. The offender’s progression through the prison system and into the community would be based on their positive engagement and authentic change.

The numbers of high-risk terrorists in prison are a small subset of an already small number of extremist offenders. Officials ought to know everything there is to know about them. Clearly in the case of Usman Khan, they did not. But for greater certainty, there is a price to be paid – and we must be very clear eyed about it and straight with the public.

We may need the indefinite detention of serious terrorist offenders beyond the end of their sentence, when we cannot demonstrate that their risk to the public has reduced to an acceptable level. While we notionally have this facility through the parole board, I don’t think it has the necessary expertise or institutional philosophy to deal with the unique threats posed by ideologically inspired offenders.

We must be able to reassure the public that in these cases the rights of citizens to be protected from terrorism takes absolute precedence over the rights of those trying to hurt us. In doing so, we then have to acknowledge an awkward truth – that in order to combat a lethal threat we have to, temporarily at least, suspend some of the liberties and protections that separate us from our foes. Additionally, prisoners without hope are extremely difficult and often dangerous to manage. We must not forget that British citizens – easy targets for alienated and ruthless terrorists – work in uniform in close proximity to these offenders every day.

So why not play safe and assume that all terrorists are irredeemable? Why not apply the US standard and entomb those whose hate western liberal democracy in the mountains in Colorado? There are good moral and practical reasons to hold out for the possibility of redemption and change, even with people who have inflicted the most grievous harm on us.

We can’t speak to dead terrorists. But those alive and in custody are a potential mine of information on how to stop future extremists being created and future plots being hatched. A recanting terrorist is worth a thousand police officers in this struggle. We must not underestimate the potency of a former terrorist ‘rock star’ who can connect with an upcoming generation of young jihadists or far-right extremists and trash the brand. You only have to look at the hysterical hatred IS has of the reformed to know how inimical they are to the terrorist propaganda machine.

The new Government needs to decide if its approach to managing the risks posed by violent extremists remains in the reclamation/rehabilitation camp that the Prison and Probation Service has created and presides over, or whether we need a much more sceptical, risk-led national security response. After Usman Khan’s terrible work and in the absence of clear evidence that the former approach is adequate, for the moment at least, we need less trust and much more verification.

Comments