Universities are facing their biggest crisis in modern history, yet most are in denial and living in la-la land. Warning bells have been ringing for some years, but the descent has been precipitous. Just 25 years ago, Tony Blair unveiled the ‘knowledge-based economy’ to be powered by universities. They stood tall, untouchable, almost universally admired. As late as 2020, despite Britain having less than 1 per cent of the world’s population and 3 per cent of global GDP, it had 11 of the world’s top universities, including more in the top 50 than the whole EU combined. London alone boasted four of the top 100, the capital outperforming some entire G20 nations, including South Korea and Japan. It was a golden age.

But now? Over half are at risk of deficit, and a worrying number teeter on with less than 30 days liquidity. It’s not just those in left-behind areas feeling the heat but well-established institutions too. Government ain’t going to be the answer. In November, Bridget Phillipson, the Secretary of State for Education, wrote to vice chancellors telling them that, in return for increasing the maximum cap for tuition fees and maintenance loans for students in line with inflation, the government had five priorities which she ‘expected’ universities to achieve in support of the Prime Minister’s missions.

‘Madness. We can’t do this. We have neither the money nor the capacity to fulfil what government expects of us. It is flogging a dead cart horse’, one weary vice chancellor told me. ‘We are being asked to do more with less’, said another. One can see their point. The financial uplift Phillipson granted them was wiped clean away by the Chancellor’s increase in national insurance contributions. The Treasury, long sceptical of university spending, has grown even more hostile. After years of almost zero economic growth, the government is broke and has more urgent priorities frankly than universities. ‘The outlook is bleak’, admits Andy Westwood, advisor on higher education to the Blair and Brown governments. A crunch point is fast approaching. Universities are critical to the government’s industrial strategy and inclusion strategies. But it cannot afford to bail out those that fail.

Universities used to be the darlings of the left and also, let’s remember, the right. ‘They’re hopeless’, one Labour insider told me before the general election. In the eyes of many on the left, they lost the plot on excessive vice chancellor pay and perks, student experience and teaching quality. For the right, universities’ failure to stand up for free speech and against anti-Semitism, their tolerance of woke and hostility to Brexit ranked high among the complaints.

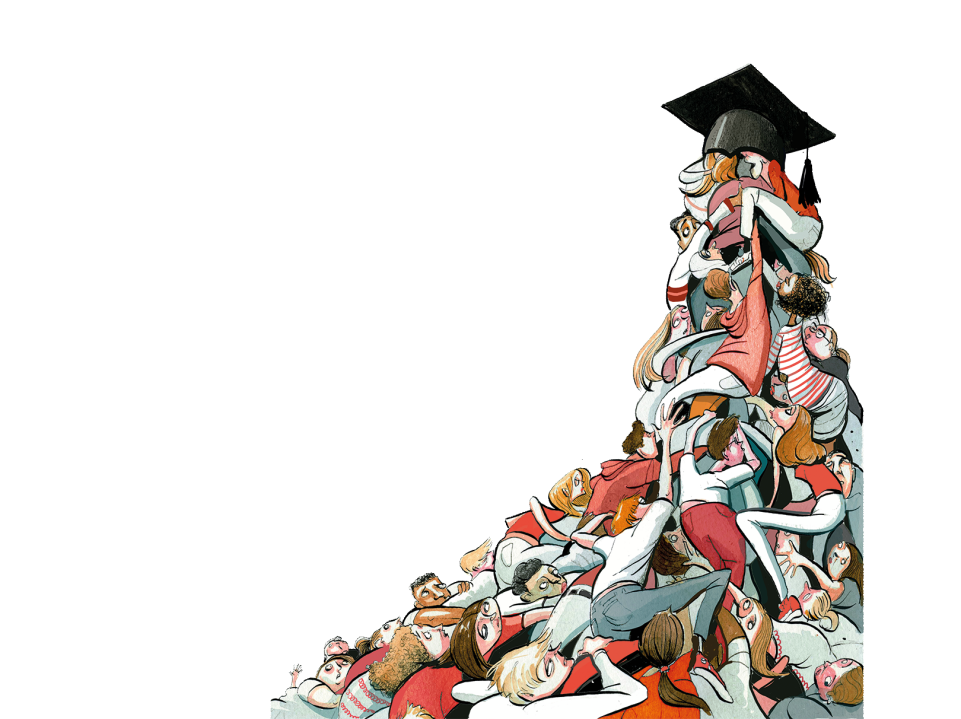

Who cared? During the bonanza years, universities borrowed big to accommodate the extra students. Now empty student blocks and lecture halls risk becoming commonplace. Although the numbers of 18-year olds will continue to rise until 2030, the proportion wanting to attend university, for multiple reasons including cost, is starting to reduce. The market is fracturing. More students want to live at home, opt for apprenticeships, or to give universities a miss altogether because of the cost and worry that the market for graduate jobs is drying up. Undergraduate numbers on some estimates will drop 20 per cent by 2040. The worry is the fall might be much steeper still for conventional three year residential places.

The stark fact is that financial model on which universities have been operating based on rising domestic undergraduate fees and overseas students paying exorbitant fees, no longer works. Numbers from abroad have fallen sharply in the last year, which means that Russell Group universities, to compensate, have been plundering domestic students from less prestigious universities, adding to their squeeze. Money for teaching as well as research is stretched to breaking point. ‘The ranking of British universities internationally, based heavily on research, is going to decline without more funding’, says Nick Hillman, head of the prestigious Higher Education Policy Institute (HEPI). That would be explosive. No government is going to want to see the much-vaunted international rankings fall on their watch. Yet no British government is going to match the investment in universities of our competitors, notably China, nor can the universities mirror the endowments in the US.

So can anything be done? Not if the sector relies on two dogs that won’t bark. Inject more cash the unions demand. But from where? The government is not going to produce it by increasing tax, nor by raising fees substantially. So that’s a brick wall. Letting financially weak universities go under is another: it would teach the cold reality of balancing books to vice chancellors and unions. But it would bring deep economic and social pain to local communities, and howling protests from Labour MPs. Merging troubled with stronger institutions is another attractive solution in theory: but in practice, no robust university will want to pick up the financial difficulties of a struggler, and inherit a newcomer who could damage its position on the league tables.

So is there any hope of avoiding the abyss? Certainly, but it will require leadership. And there will be pain. Here’s how to do it. Liberalising visas for overseas students and staff, while politically fraught, must be implemented. So too should adopting new technology. Are they prepared massively to champion and re pivot to AI and new technologies? Not on your life: ‘most universities are like rabbits in headlights when it comes to AI, not knowing where to spend the money, nor where exactly the savings will be experienced’, says Hillman..

Learning from trailblazing universities abroad is essential. Malcolm Grant, former president of UCL points to Arizona State University which ‘combines internationally ranked research with educating a diverse range of students online across the country, a model other US universities are emulating’. The French ‘federation’ model, inaugurated by former President Nicolas Sarkozy, achieving significant economies of scale, is another to consider. At home, London Southbank university is leading the way by offering students of all ages a mix of traditional university, further education, apprenticeships and work-based learning.

If the sector does not get ahead of the curve right now, it will be forced into reacting, with years of misery, redundancies and retrenchment ahead with suboptimal outcomes. Is that what university leaders and unions want? I think not. So who should spearhead this revolution? Certainly not government, which is incapable of providing such solutions, for all the touching faith the university sector has in it. No, the only viable solution is for the sector itself to take charge of its own destiny. The body that represents vice chancellors, Universities UK, must spearhead the charge. It has been picking up the gauntlet under its dynamic head, Vivienne Stern but needs to go far beyond its current ideas: nothing less than the biggest reset in the history of universities will do.

The key is anticipating future student, job market and research needs, and devising a radical and flexible higher education formula combining physical and online education. In many cases, this will mean universities drastically slimming down and rethinking their entire structures and place in society. Selling off or repurposing student accommodation would help provide cash. New markets and cash can be found too offering more flexible courses, and connecting with the over-50s who never attended university but have money to spare: attractive modules to enrich their lives and teach them new skills could be offered. That alone would be transformative.

British universities can enjoy a golden era again if they act decisively now, achieving a new identity regionally as economic and cultural powerhouses and nationally as drivers of economic renewal. I have always loved universities, and being a vice chancellor was the high point of my career: but I want to see the sector forge ahead not recede in this new and very challenging era. The time has come for universities themselves to channel the unrivalled brainpower at their disposal to solve the problem that they in part have created – before it is too late. The clock is ticking.

Anthony Seldon is a former Vice Chancellor of the University of Buckingham. His latest book is Truss at 10. How not to be Prime Minister.

Comments