It is hardly surprising that the new parliamentary complaints system has had what might politely be termed teething problems when it comes to helping staffers and others who turned to it. This week the Times reports that complainants had been given incorrect advice, had not received the mental health support they needed, and were even discouraged from pursuing some complaints.

Ever since MPs started discussing the need for this independent complaints and grievance scheme, there has been serious confusion about its remit, including over whether it can deal with older complaints and who is able to complain. Even those closely involved in setting up the new system seemed confused about what it would be doing: MPs who discussed it with Andrea Leadsom and parliamentary authorities would regularly leave with conflicting impressions of how it was going to work. The service has said it is running an 18-month review of how it has worked so far and has encouraged those who have turned to it to offer their feedback.

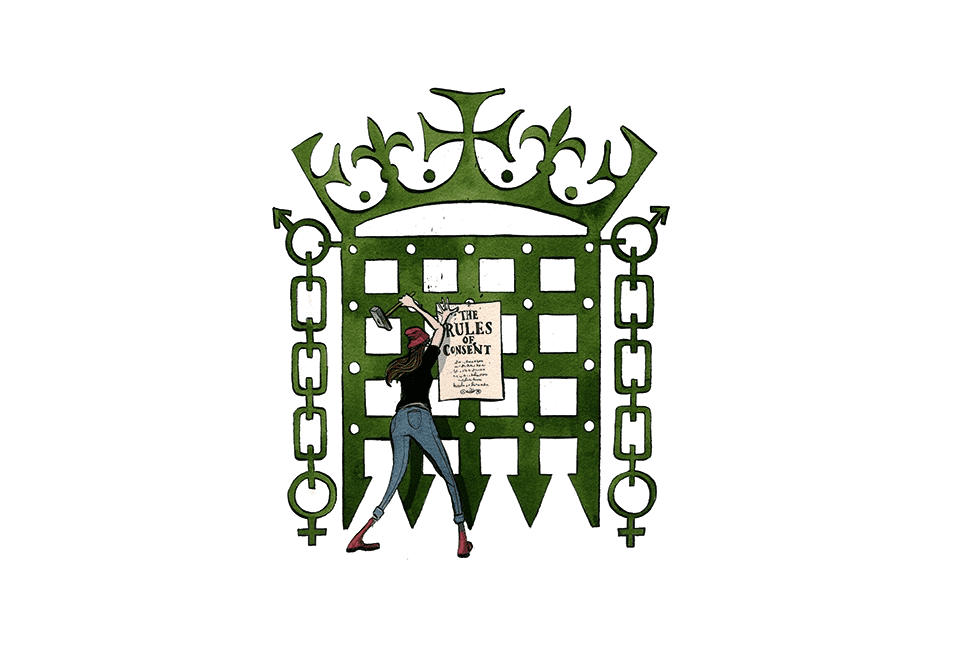

MPs are given a poor blueprint for how to treat people when they themselves are standing for parliament

Perhaps this review will solve the teething problems. But equally unsurprising — and even more dispiriting — is that the need for staffers to complain doesn’t seem to be going away. About one in seven of the staff hired by the 2019 intake of MPs have already left. In some cases, this will be because these new recruits turned out not to be suitable, but in others it will be because of an oppressive workplace culture. It is all very well setting up a system by which someone who has been treated appallingly can complain. But it is better to prevent these situations arising in the first place.

As I explored in my book, Why We Get The Wrong Politicians, there is currently little to no training or HR support for MPs. They learn how to do their jobs and manage teams of staff in two different parts of the country as they go along. For many, this is the first time they’ve ever managed a team. Others come from toxic working environments, including within government itself. All are given a very poor blueprint for how to treat people when they themselves are standing for parliament: candidates are expected to spend years working for free, making extraordinary sacrifices in their personal lives and surrendering all their free time. They are often belittled by those in charge of candidates in their central parties, particularly as election time approaches. It is therefore no wonder that a significant minority of MPs end up being extremely poor managers.

To compound this, they tend to employ young, eager but inexperienced people as researchers. These employees don’t always have the confidence to tell their boss that they don’t want to do something. They don’t always know what is and what isn’t normal in a working environment. They do not receive appraisals with anyone outside the MP’s own team and therefore have little opportunity to ask such questions or raise concerns until a situation has escalated.

MPs have now been offered training on how they should be treating their staff and one another. But it remains voluntary and take-up is poor. Often the people who assume they do not need such training are those who could benefit the most from it. It would be far better were it compulsory for any MP using a staffing budget from IPSA (which funds all MPs’ operations) to take the training.

Many MPs also baulk, rightly or wrongly, at ‘unconscious bias’ training. But few would have such a reaction were they offered courses in ‘leadership’ which covered the same ground as anti-harassment and anti-bias training. If parliament is serious about cleaning up its act, it cannot just wait for people to complain. It needs to do more to stop the situations that lead to complaints in the first place.

Comments