The latest headmaster of Eton has been recruited from a major private equity firm to help drive the brand’s growth in China. The consortium of hedge funds that own Winchester has been involved in a bitter takeover battle with Rugby, centred mainly on the redevelopment value of its playing fields. Westminster has been acquired by Meta, the owner of Facebook and WhatsApp, to develop campuses in the Metaverse, Netflix has acquired Marlborough to use as a set for romcoms, while Elon Musk has taken control of Ampleforth, sacked most of the teachers and rebranded it as ‘W’ for reasons that no one can quite fathom.

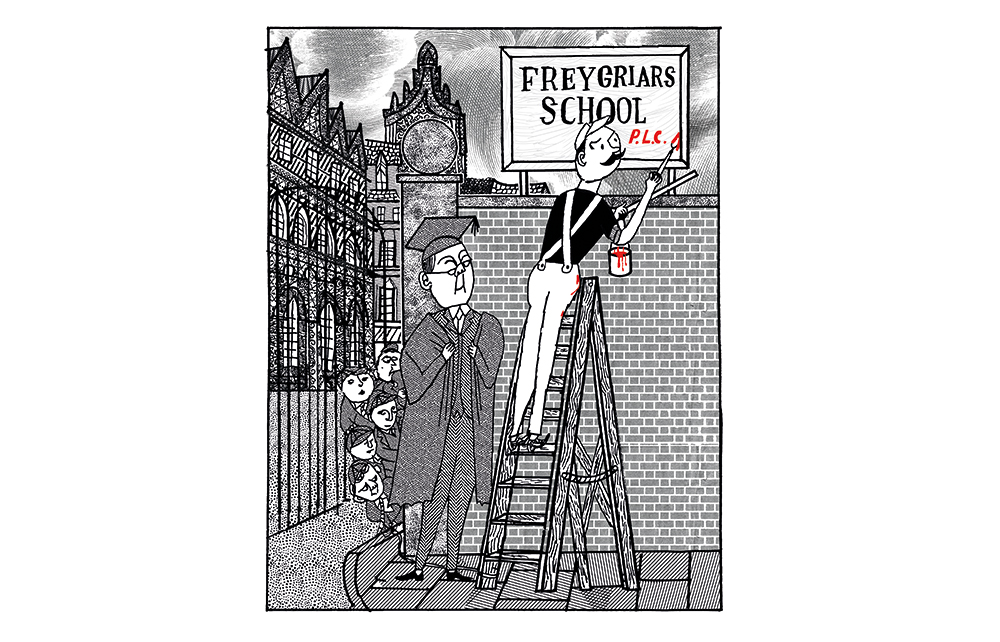

Forcing schools to turn themselves into private companies will change the way they operate

This all may sound fanciful, but fast forward to 2027 or 2028, and that could well be a selection of headlines plucked from the business pages. The serious point, however, is this. Once the Labour party removes the charitable status of private schools, as seems inevitable, the whole sector will change dramatically and start operating far more like a normal industry. That may be better in some ways, and worse in others, but it will make all private schools very different from the institutions we are familiar with today.

Labour is committed to abolishing the charitable status of private schools and imposing VAT at 20 per cent on the fees they charge. Of course, it has promised that reform before and – much like abolishing the House of Lords – somehow never got around to it. Yet this time it looks more serious. The pledge has featured far more prominently in Labour’s campaigns than it ever has in the past, and the money it would raise has been spent several times over by most of the shadow cabinet. (The estimated £1.6 billion it would rake in would be enough to save the NHS, rescue the welfare system and launch a green industrial strategy, with some change left over for foreign aid as well.) On top of that, Sir Keir Starmer’s government, if it is formed next year, will be so thin on radical policies that it may have to do something to placate its left, and an attack on private schools will be one of the easiest ways of doing that. If the party gets elected, it will almost certainly happen.

Many parents may simply decide that any hike in a private school’s current fees – which can be £40,000 or more each year – is unaffordable and turn to the state system instead. How many will do this we don’t yet know. However, an analysis by the Institute for Fiscal Studies has pointed out that the demand for private schooling has remained very steady at around 6 to 7 per cent of the market, despite a 22 per cent real-terms increase in fees since 2010 and 55 per cent since 2003. That suggests parents will pay up almost whatever is charged. It estimates that VAT on fees, and charging business rates for premises, would bring in around £1.6 billion annually, offset by an extra £100 million to £300 million of spending on state education for the 3 to 7 per cent of students it thinks will drop out of the private sector. We will find out if it happens. And yet one point is surely clear, even if little appreciated so far. By forcing schools to turn themselves from charitable foundations into private companies, it will change the way they think, operate and act. They will become businesses. We will have a private education industry.

In a minor way, we already do. Even though there are substantial benefits to charitable status, such as significant reductions in business rates, along with an exemption from VAT on the fees they charge, there are also some disadvantages. Schools have to demonstrate that they are offering a significant public benefit, either by sharing facilities with the wider community, or offering lots of generous bursaries, and they can’t raise capital in the way that a normal company can. Estimates vary, but between 30 per cent and 50 per cent of the 2,600 private schools in the UK already have a corporate structure instead of operating as charities. There are some quite substantial chains of private schools run for profit, such as the Alpha Plus group, with a portfolio of schools that includes Wetherby, Prince William’s alma mater, or Wishford Education, which has a collection of mainly prep schools.

It remains to be seen how the transformation would happen. If a school decides to incorporate, its trustees will have to work out who gets the often valuable assets at stake. They could offer the ‘equity’ to the staff, along the John Lewis model perhaps. They could offer it to the existing parents, or perhaps to the entire alumni, in a similar way to the building societies that demutualised in the 1980s and 1990s. For a lucky few, that could mean a huge windfall (allowing many alumni to afford the increased fees for their own children, perhaps). But however it happens, it seems likely that over a few years the vast majority of schools would turn themselves into companies.

That would just be the start of the transformation. Companies driven by shareholders, and by the requirement to deliver profits and make a return on their capital, naturally start to operate in a far more commercial way than a sector dominated by charities. Think of the difference between Zara or Next and the charity shop on your local high street. They both sell stuff, but they have a completely different feel to them, and they are run in completely different ways. So how would the ‘schools industry’ start to change once it was completely incorporated? No one can say for sure. Industries evolve in lots of unexpected ways. But here are four big trends to start with.

First, management will be professionalised. No one would want to disparage the people who run schools, and the teaching is often excellent, but when an organisation is run as a charity over 100 years or more it doesn’t typically have the cutting edge that you would expect from a purely private company. Expansion plans are often shambolic. Fees are lazily put up at whatever the inflation rate happens to be, typically with a couple of points added on, instead of looking at ways to streamline operations or to deliver better value for money. New technologies are generally kept to the ‘design and tech’ department without anyone thinking about how they might be applied to the product that is being delivered. There is seldom much sign of innovation or fresh thinking. We can expect ‘schools management’ to become a mainstream profession, attracting a whole generation of new people into the sector alongside teachers. Over time, schools will be far better run than they have been in the past.

Next, the very best schools will be turned into global brands. The UK is perhaps unique in having a handful of schools with names and a history recognised around the world. At the same time, British educational standards are widely admired, and English is compulsory for anyone who wants to make a career in business, academia or the professions. We can expect that at least a number of schools, with their new owners looking at delivering returns for shareholders, will set up campuses around the world, especially in markets such as China and the Middle East (look at the way Harrods is in Beijing and Qatar as well as Knightsbridge). The best-known ‘brands’ will steadily globalise, and become less and less dependent on their domestic market.

Thirdly, some schools will undoubtedly be asset-stripped. There are many schools, and plenty of prep schools in particular, that are sitting on lots of valuable land. All those cricket pitches and netball courts might earn a lot more if they were ploughed up for houses or office developments, especially if they are in the leafy suburbs of the Home Counties where space is precious. Alternatively, many of those buildings might make attractive apartments if they were converted. Once a school has been privatised, there will be lots of space for takeovers, with the school itself closed down, and all the property redeveloped. Some of the wheeler-dealing may well get very unscrupulous. That is almost certainly not what the Labour party intends, but is surely inevitable when you turn a whole sector from charitable to a commercial endeavour.

Some schools will undoubtedly be asset-stripped. There are many sitting on lots of valuable land

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, different types of school will emerge. One of the oddest features of the British school industry is the way it has raced upmarket, with every school fitting itself out with ritzy playing fields and Olympic-sized swimming pools. It is as if there were only Jaguars and BMWs available in the car industry, and no Nissans or Fords, or only Ralph Lauren and Burberry selling clothes, with no M&S or Primark. Especially once VAT at 20 per cent is added on top of the existing fees, the real niche in the education market will be for more moderately priced schools, using technology and simpler premises to deliver higher-quality teaching at lower cost. Others will specialise in different types of education, subjects or learning methods. We will see. The significant point is that once it is run on purely commercial lines, a whole range of different ‘products’ will emerge offering slightly different experiences and price points, just as they do in every major industry. For many parents that will be a relief.

In many ways, the private school ‘industry’ will be a lot better when it operates purely commercially. Charitable status masked a lot of failures and, even more, tolerated a lot of muddled management. In time, private schools will be a lot more responsive to parents’ needs. There will be a greater range of products and price points. Good schools will take over bad ones. The very best will expand globally. But a lot of schools will also disappear, and others will be asset-stripped. A leaner, more responsive industry might emerge, but there will be a lot of painful disruption along the way.

Comments