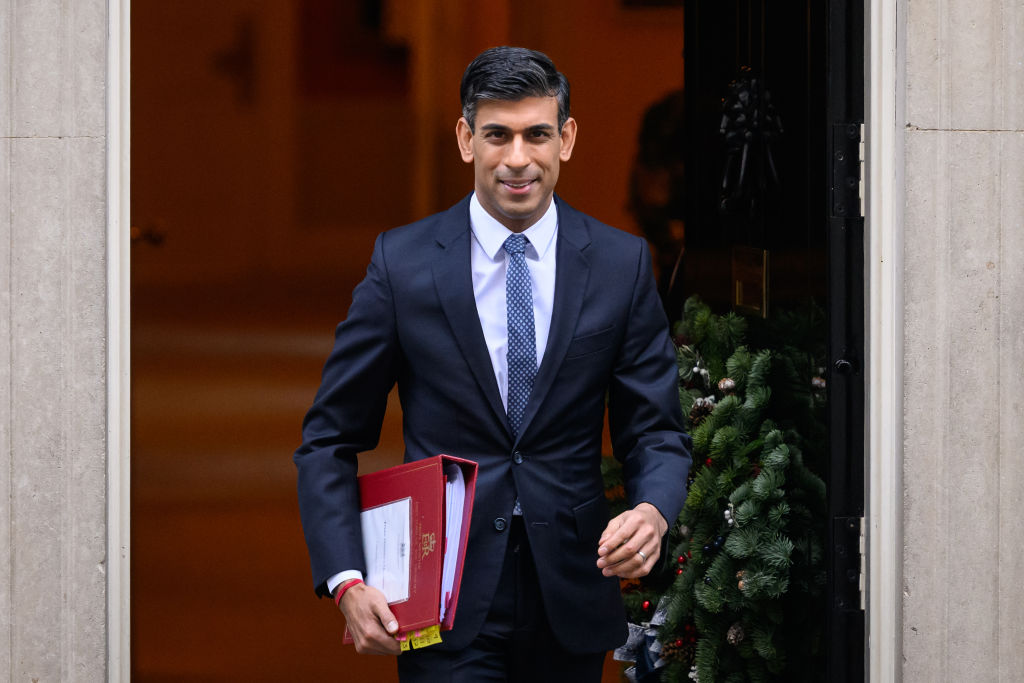

Rishi Sunak is getting tough. Goaded by Labour’s systematic painting of him as ‘weak’, the Prime Minister has threatened ‘unreasonable union leaders’ that if they do not call off their Christmas strikes, he will introduce new restrictions on their ability to take industrial action.

The desire to be ‘tough’ with trade unions is one of the few issues which unites the Tory party – apart from cutting taxes and reducing the size of the state, which Sunak feels unable to deliver at the moment. This is a Conservatism shaped by Margaret Thatcher as she destroyed the post-war consensus, one of the central features of which was the incorporation of the unions into managing the economy, something she saw as tantamount to appeasement.

Sunak is currently unwilling to concede to the unions’ demands but is unable to alleviate the impact of the strikes either

Thatcher’s ghost still stalks the corridors of Conservative Campaign Headquarters and Sunak’s mooted legislation has inevitably invited comparisons to her implacable approach to industrial relations. But, in fact, Sunak’s position more accurately evokes that of Labour Prime Minister Jim Callaghan who replaced Thatcher in May 1979.

When Thatcher took on the unions, she did so with overwhelming public backing and only fought battles she had carefully prepared for. The various Employment Acts she introduced – which made sympathy strikes illegal and reduced the scope of picketing and other limitations – were introduced in the shadow of the 1978-9 ‘winter of discontent’. This saw 12 million working days lost and came after a decade of consistent industrial unrest. The public were fed up, and in her first year as Prime Minister 72 per cent thought unions had too much power. When the miners’ leader Arthur Scargill called a national strike in 1984 Thatcher was well-prepared: she had ensured coal stocks were high so the country could survive a prolonged shutdown. Scargill’s defeat was almost inevitable.

Sunak enjoys no such advantages. Largely thanks to Thatcher the trade union movement is no longer regarded as much of a menace. When asked in 2017 only 36 per cent believed the unions were too powerful. The present strike wave comes after over 30 years of union quiescence. Even if all the threatened December strikes happen the number of days lost will still be less than 10 per cent of that which occurred during the winter of discontent. And while during the autumn there has been a slight uptick in those who believe unions play a negative role in Britain it is equalled by those who think they play a positive one. Just now the unions have more of the public on their side than against them: as YouGov has found, exactly half of Britons support paramedics and ambulance workers going on strike while 48 per cent oppose Sunak’s threatened legislation. Maybe these numbers will shift in the government’s favour when the strikes hit but the public is much more positive about the unions than it ever was during Thatcher’s early years as Prime Minister.

Even more worryingly for Sunak, there is no equivalent of accumulated coal stocks to see the country through these multifarious disputes. When members of the RMT strike, trains stop immediately; when nurses walk out, waiting lists right away get longer; and when border staff stay at home, queues at airports in an instant become intolerable. His proposed legislation can do nothing to address these disruptions: if he is lucky, it will become law by Easter 2023 – not Christmas 2022.

All of which leaves the Prime Minister looking weak. He is currently unwilling to concede to the unions’ demands but is also unable to alleviate the impact of the strikes either. Even the army seems unwilling to take the absent workers’ place.

If any comparison is apt, therefore, it is less with the all-conquering Thatcher and more like the helpless Callaghan. Wanting to keep inflation pegged, in the autumn of 1978 the Labour Prime Minister said that public sector workers should only expect a 5 per cent pay rise. The resulting strike wave ended any hopes he had of retaining power because the piling bags of rotting rubbish revealed his government’s incapacity to govern. That is the danger for Sunak: talking tough might please his backbenchers but Britons will want solutions and will turn to the party which looks best able to manage the situation – if they haven’t already.

Comments