Scottish multi-millionaire Sir Tom Hunter is frustrated. Speaking to the BBC’s Today programme to promote a new report commissioned by his foundation on Scotland’s economy, he said: ‘The general consensus in business up here is that the current government don’t really listen to business. They make policy in isolation, which makes bad policy, and that’s not good enough for Scotland in my opinion.’

Sir Tom, who famously started out selling trainers from the back of a van before going on to make hundreds of millions in retail, wants to see Scotland’s private sector given the tools and assistance it needs to turbo-charge the economy. His paper, produced by consultants Oxford Economics and entitled Raising Scotland’s Economic Growth Rate, aims to stimulate the debate needed to make that happen.

The paper addresses low productivity, poor business birth rate and a lack of success in businesses scaling up, pointing out, for instance, that Scotland’s business birth rate came ninth out of 12 UK nations and regions in 2019. It considers policies under three headings:

- Increases in government borrowing and/or cuts in interest rates to stimulate stronger growth in demand and hence output

- Significant tax cuts and deregulation to improve competition and incentives in the economy

- Large increases in government support for businesses, either directly or through increased spending on infrastructure, education and skills, innovation, or the green economy.

Scotland’s politics, rather than the structure of the economy, is the major block to change.

The paper is useful in some areas, not so useful in others, and avoids one very big elephant in the room.

It starts by providing an up-to-date, in-depth state-of-the-nation summary of Scotland’s economy. This is useful for highlighting strengths, weaknesses, and in setting the scene for policy discussions. Less useful is the lengthy high-level outline of macroeconomic challenges that could apply to any state, and which seems incongruous in a paper aimed at legislators in a sub-national parliament. The paper also fails to adequately consider the tensions or trade-offs involved in policy objectives: more borrowing but also lower tax; less regulation but also a ramping up of government intervention.

In amongst the policy discussion are some useful nuggets. As others have highlighted, Scotland’s economic policy landscape is a mishmash of agencies, strategic boards, action plans for this and conventions for that. Scotland needs fewer policy objectives, argues the paper.

At present, the Scottish government has a list of six priority sectors: food and drink (including agriculture and fisheries), creative industries (including digital), sustainable tourism, energy (including renewables), financial and business services, and life sciences.

The paper argues that, particularly with the COP26 climate change conference coming to Glasgow this year, there is a case for making addressing climate change, including the promotion of renewable energy, the ‘single heart’ of a Scottish industrial policy, ‘supported by measures that encourage a more competitive economy, and the expansion of demand to ensure that the resultant economic growth is not choked off’.

The paper suggests the new Scottish National Investment Bank (SNIB) should have its remit altered to focus on renewable energy, aiming to make it the core of a new green venture capital community in Scotland, with universities and the financial sector all wired into this linchpin growth sector. A real Silicon Glen for the 21st century.

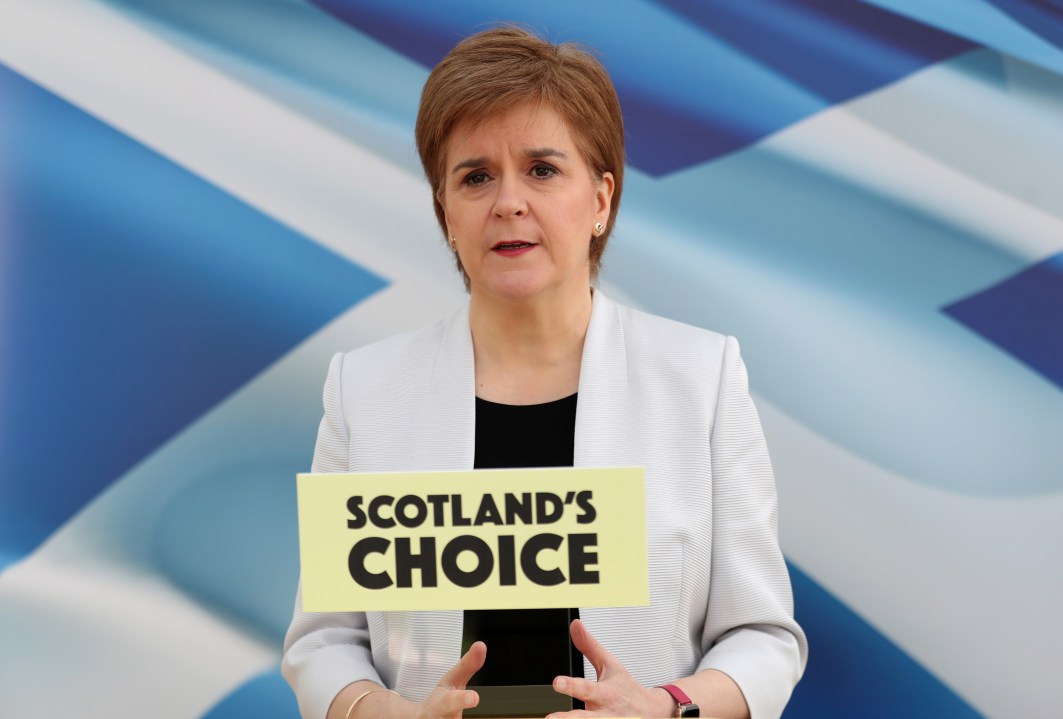

It is an interesting idea, and potentially an achievable one. There are, however, two big obstacles to progress. First is the SNP government’s lamentable record in industrial policy, particularly when it comes to renewables. Polling suggests the Nationalists will form the next Scottish government after May’s Holyrood elections.

The other obstacle is the elephant in the room: independence. The paper states up front that it is neutral on this issue. But the separation of Scotland from the UK is the Scottish government’s primary aim, and the implications of that policy are so profound that they cannot be set aside when discussing the country’s economic development potential.

Sir Tom might want to see Scotland achieve emerging market levels of economic growth, but the SNP threatens to engineer the structural risks of an emerging market into Scotland without the growth upside. Cutting Scotland off from its current treasury and central bank support and creating trade friction with its biggest trading partner are hardly conducive to stimulating growth. And even if leaving the UK never happens, the Scottish government’s policy agenda will continue to be skewed and driven by the constitutional issue.

Sir Tom’s efforts to stimulate debate and change should be applauded. But he looks set to continue to be frustrated. Scotland’s politics, rather than the structure of the economy, is the major block to change, and those politics are stuck in a rut.

Singapore on the Clyde is still a long way off.

Comments