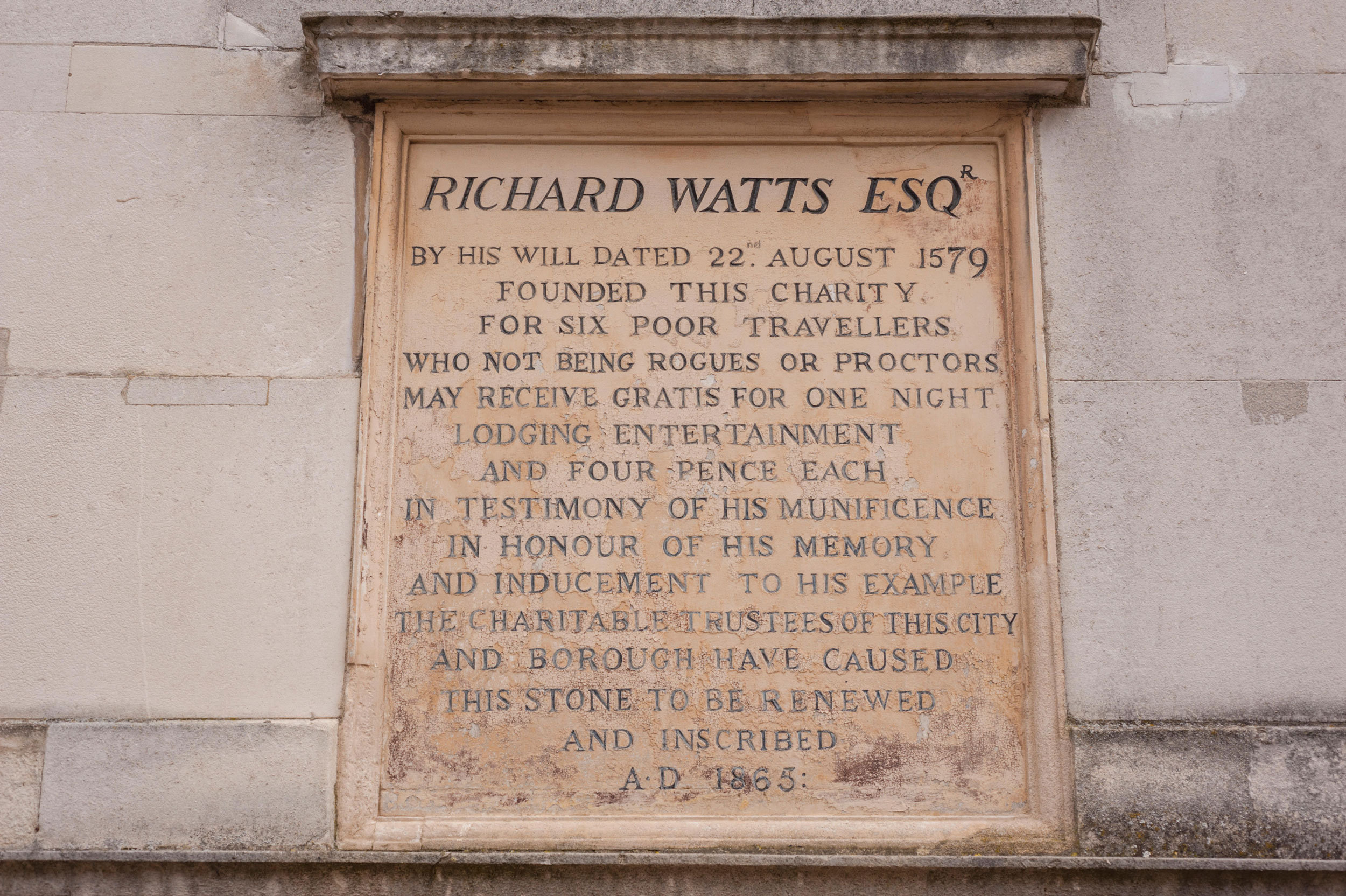

In the vestry of the church where my father was priest, there was a large wall-mounted plaque commemorating some long-dead worthy of the eighteenth century. I cannot recall his name, but he left a large bequest to the parish for the support of ‘poor persons known to be of good character.’ There are similar inscriptions marking similar bequests in churches up and down the country – though perhaps fewer of them now, in these days of fervent ideological scrutiny of such memorials.

As an idealistic young man, I used to find the plaque rather irritating. I thought it was archaic and unchristian, a relic of the Bad Old Days when the gentry’s arbitrary prejudices about the undeserving poor led to misery and injustice among the working class. And I was right to exercise considerable scepticism about the old system of parish relief, with all its cruelties and inconsistencies.

But there was a point that my indignant 18-year-old self missed: the plaque harked back to a model of charity and welfare that held some important lessons for our own time.

Being intensely local by design, it embodied and reinforced the social contract in a way that is hard to replicate at a large scale. It was clearly understood by all involved that this was an arrangement between members of a single community, who knew each other and who were in some sense mutually accountable. The man who took more than his share of charity, or took charity to which he was not entitled, or squandered the charity he had been given, would generally feel the consequences of that misbehaviour in pretty short order. No able-bodied man could expect to subsist indefinitely ‘on the parish’ if work was available, and new arrivals – especially large groups of new arrivals – would not be entitled to support.

The contrast with our enormous and impersonal system could hardly be more pronounced. It was reported recently that something like a million households with at least one foreign-born claimant are in receipt of benefits. Nearly half of all social housing households in London are headed by someone born overseas. There is also growing disquiet about the Motability scheme, by which the taxpayer heavily subsidises new or nearly-new cars for people in receipt of disability benefits – but not simply people with physical disabilities. For example, one survey suggested that nearly a third of those claiming disability benefit for anxiety were found eligible for Motability, and 22 per cent of those with depression. Local authorities meanwhile spend huge amounts of money on taxis to school for children with additional needs. The perverse incentives generated by such arrangements are obvious.

More than 20 years ago now, in 2004, the writer David Goodhart caused an enormous stir with a piece about the sustainability of the welfare state. Goodhart’s argument was that the huge growth in ethnic diversity in Britain during the second half of the twentieth century posed a threat to the social solidarity on which a welfare state ultimately depends. Put simply, at the level of the national community, citizens want to be satisfied that if their money is going to be taken from them by the government and given to other people, those people are like them – that they have the same kind of priorities and attachments, that they have contributed to the country and to the Treasury, and that once they are able to do so they will support themselves. This conclusion was already backed up by a great deal of sociological data in 2004, and further research has tended to confirm it. Ed West’s The Diversity Illusion updated and expanded upon the Goodhart thesis.

In demographic terms, the country has changed vastly even since Goodhart set the cat among the pigeons. Back then we were just beginning to feel the effects of the New Labour immigration policies, but the 2021 census found that one out every six British residents was born overseas (in 2001 it was 8.3 per cent, or one in twelve), and that was before most of the huge expansion of legal immigration that took place under Boris Johnson. By 2031 the figure could well be over 20 per cent, and even many of those actually born here will be the children of newcomers, meaning that we are looking at a scale of change totally unprecedented in our history. It is not hard to see how this transformation might render the welfare state in its current form highly unpopular. Parties that wish to continue large fiscal transfers to newcomers who have not contributed to the system, and who are indifferent or ill-disposed towards the host society, will simply not get much support. Our serious shortage of housing is likely to feed into such discontent, fraying the social contact yet further.

The other side of the social contract problem, separate from demographics, is the sharp rise in people being signed off work on grounds of disability. Approaching 8 per cent of the working-age population now claims disability benefits, and this figure has almost doubled in the last 20 years, with most of that increase taking place since the Covid pandemic. Many of these people have vague and over-diagnosed psychological problems like ‘anxiety’, ‘depression’ and ‘personality disorders’; others have the ill-defined ‘long Covid’. While some of the cases will clearly be genuine – clinical depression can be crippling – there is a point at which the welfare system will fall into irretrievable disrepute if significant numbers of people who are basically capable of work, but are encouraged and enabled to think of themselves as unable to do so, are seen to be enjoying a comfortable life at the taxpayer’s expense.

We cannot and should not return to the era recalled by the plaque in my father’s vestry. The reliance on patrician benevolence and the vagaries of local almsgiving had all its own limitations and horrors. But nor can we simply assume that the current system can simply tick over for ever. It was set up to serve a particular people in a particular place, with the contributory principle at its heart and, where social housing was concerned, an explicit prioritisation of those who had behaved well and paid in – although this has since been abolished in favour of a ‘non-judgmental’ needs-based assessment. It may not be infinitely adaptable to an age of enormous population churn, sharp declines in social trust, and a therapeutic culture that leads to huge over-diagnosis of mental health conditions.

Comments