When the photographer Ida Kar (1908–74) was given an exhibition of more than 100 of her works at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1960, history was made.

When the photographer Ida Kar (1908–74) was given an exhibition of more than 100 of her works at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1960, history was made. She was the first photographer to be given such an honour — a substantial solo show in a public gallery — and the presentation of her photographs was carefully considered. This set a precedent for subsequent photography exhibitions and brought the question of whether photography is art firmly to the forefront of debate.

The person responsible for all this was the dynamic and innovative director of the Whitechapel, Bryan Robertson. Which makes it all the more bizarre that there is no photograph of Robertson in the current celebration of Ida Kar’s magnificent photos at the National Portrait Gallery. She certainly took his portrait, but it is not included here — along with several other significant omissions: the brilliant shot of Craigie Aitchison, for starters, and good photos of Gillian Ayres, Victor Pasmore, William Scott and Roger Hilton, among others.

However questionable the selection, the exhibition does give something of the distinctive flavour of Kar’s vision. An Armenian, she was born in Russia, moved to Egypt in 1921, studied in Paris in the late 1920s, and set up her first photographic studio in Cairo in the late 1930s. In 1944 she met the charismatic Victor Musgrave and came to London, where he started an avant-garde art gallery. Her cosmopolitan background undoubtedly made her responsive to artists from Soho to St Ives, and she developed an ability to capture them in revealing pose or context. (The telling informality of her work would seem to have been an inspiration to Snowdon.)

The critic and curator Jasia Reichardt recorded Kar’s technique: ‘She talks rapidly while looking around, then starts shooting a single roll of film of 12 shots only, from which the best are selected for printing. The job takes half an hour so that no one has time to get bored. She relies mostly on available natural light and likes strong contrasts. The results: simple, powerful, unaffected, but often dramatic formal revelations of character.’

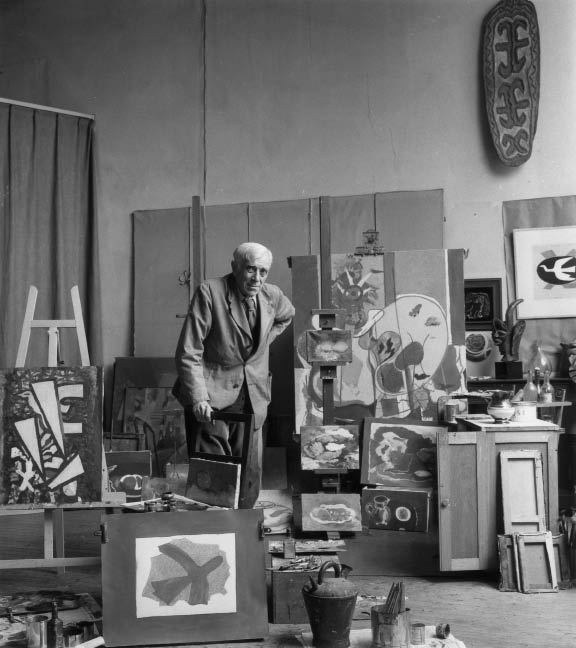

Kar was particularly good on the cultural world. She pictured actress Sylvia Sims in 1953 looking almost as innocent as she did in Ice Cold in Alex five years later. Henry Moore is dramatically lit at the end of his sculpture store with a couple of casts of ‘Family Group’ (1949). Chagall looks wonderfully knowing; Foujita — rather like Stanley Spencer — is set disquietingly against a backdrop of dolls; Spencer himself is placed under an umbrella looking quizzical in old clothes. (Didn’t he know it was bad luck to open one indoors? He was dead in five years.) There’s a nice grouping of younger painters: Piper, Hitchens and Sutherland. Hitchens is seen with a wall of figure drawings of archers and musicians, Sutherland looks faintly menacing and his wife bored, while Piper is baleful. (I prefer the shot of him sitting atop a ladder in his studio.)

Among other memorable images are a tough one of Léger, like a builder or plumber, Man Ray in a tartan waistcoat, Severini deadpan in a forage cap of newspaper and John Bratby ticking off his infant son. André Breton and T.S. Eliot are differently revealing, and there are lovely character-filled studies of Arp and Braque in old age. For contrast, a girlish Sandra Blow and the scrumptious Maggie Smith. There’s an unexpected eroticism to a couple of the photos: Bridget Riley in slacks tightly laced over her buttocks (not in the exhibition), and the writer and actress Hanja Kochansky, reclining on a chaise-longue, nude, pregnant, with an older child. But on the whole it is for insight into character and period that we go to Ida Kar’s work. In 1999, the NPG purchased her surviving archive of 10,000 negatives, so we shall doubtless see more of it in due course.

A group of seven previously unseen photographs by Kar of the Indian artist F.N. Souza (1924–2002) will be on show briefly at the Grosvenor Gallery (21 Ryder Street, SW1, 31 May to 4 June) before being exhibited in India (New Delhi, Bombay and Goa) in October. Souza’s spiky expressionism is now much sought after, a far cry from the late-1950s when his work could be purchased for a few pounds. Meanwhile, a fascinating exhibition at the Grosvenor of the contemporary Indian sculptor Dhruva Mistry (born 1957) has been extended to 1 June. Mistry is well known in England, arriving to study in 1981 and making his home here until he returned to India in 1997. Apart from regular appearances in the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition he has rather disappeared from sight in recent years, and this show marks a very welcome return to prominence. Mistry is a sculptor of true inventiveness and original vision and deserves wider appreciation.

At Marlborough Fine Art (6 Albemarle Street, W1, until 4 June) is an intriguing exhibition of oils and watercolours by John Hubbard (born 1931). The American-born artist has been resident here for the last half-century and although he has enjoyed a long career of painting abstracted landscapes in oils, the medium turned on him seven years ago and started to give him asthma. Forced to stop he worked instead in watercolour and charcoal.

This exhibition marks his return to oil in a dozen ‘Nocturnes’, shown with some of the watercolours which led up to them. Entering the Marlborough is like venturing into an enchanted cavern, sea-wracked or deeply forested, the mood mysterious and veiled. Slim vertical shapes dance and writhe like limbs or trees, intertwining, knotting, seeking release. Hubbard’s beginnings in Abstract Expressionism may be discerned here, but also his love for the curtains of dense vegetation to be found in the world’s great parks and gardens. Endless forked branches seem to suggest the circuitous nature of existence, and a pattern of interconnectedness that many will find uplifting.

Robert Dukes (born 1965) presents his third solo show at Browse & Darby (19 Cork Street, W1, until 3 June) with a strong selection of the still-life paintings for which he has become known. Among the best things here are a group of four paintings of liquorice allsorts and a wall of heads inspired by Old and Modern masters. (Particularly effective are the studies after Balthus.) Further down the road is a group show entitled The Geometry of Painting at Medici Gallery (5 Cork Street, W1, until 7 June), which explores similar territory to Dukes’s heightened realism. Of the artists showing here, the most original seems to be Charlie Millar (born 1965), whose passionate still-lifes explore pattern and fragments in fruitful symbiosis.

Very last chance to see Anthony Eyton’s Spitalfields paintings at Eleven Spitalfields (11 Princelet Street, E1, until 28 May but continuing on request). Eyton set up studio in nearby Hanbury Street in 1968 and continued to paint the East End (with or without figures) until 1984, returning this year to draw it again. His paintings and pastels are a vibrant celebration of a very particular area. And at Agnew’s (35 Albemarle Street, W1, until 27 May, but work available on request) is the sculptor Tim Pomeroy (born 1957), exploring the intersection between the organic and the machine-made in sensuous stone carvings of great subtlety. Whether he carves a roll of string from Carrara marble, an axehead from Cumbrian slate or a starfruit from Portland stone, his sculptures hover beguilingly between pure form and representation. Inspired.

Comments