Your enemy’s enemy is not necessarily your friend. That is something forgotten too easily. Nevertheless, though he may not be your friend he may, for a time at least, be your ally.

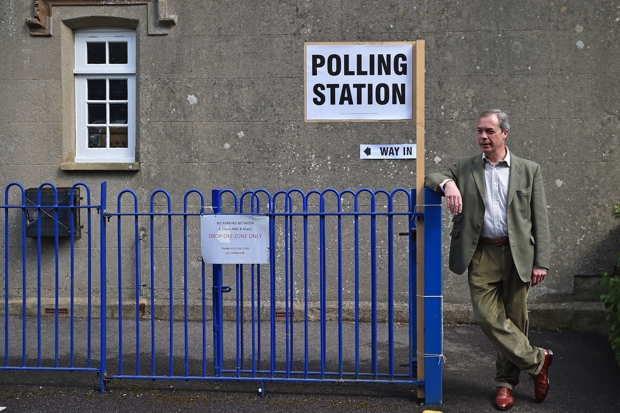

And so it came to pass that Nigel Farage is, for the time being, Labour’s new best chum. In Scotland, that is. The Tories are quite pleased with him too and, if anyone could find them, perhaps the Liberal Democrats would be too.

Of course, officially, there is much tut-tutting and hand-wringing over Ukip’s success in Scotland. We’re all supposed to be simply appalled that these fruitcakes have won a seat in the European parliament. Terrible stuff.

Come off it. These are the lamentations of a crocodile. Secretly – and sometimes not so secretly – Unionists are delighted by Farage’s success in Scotland. He was supposed to be Alex Salmond’s useful nutter; instead he has become the Union’s secret weapon.

It is hard to see how the euro results could have gone better for the Unionist parties. (Unless, granted, you’re a Liberal Democrat.) The Tory share of the vote held up (17 per cent is these days a decent result), Labour’s share increased by five points and the SNP was contained, held below 30 per cent of the vote. If this election was supposed to put a spring in nationalist steps it failed to do so. Yes, the Nats topped the poll (as everyone expected they would) but they had high hopes of a third seat and those hopes were dashed. Only narrowly, it is true, but dashed all the same.

A third SNP seat would have put a very different spin on everything. The Nats would have ‘momentum’ on their side and destiny would be calling them to rally again in September. Scotland would be on the march, you see.

Instead, however, the SNP was checked. It won but it did not win decisively. Most importantly, as Adam Tomkins correctly observes, Ukip’s success demolished a central part of the nationalist narrative justifying independence.

That story runs that Scotland is a couthy social democratic country but England is a vicious place populated by heartless neoliberals and it is crazy to think that places with such different — and diverging! — political cultures could ever be part of the same country.

Ukip were supposed to prove that. They were supposed to do very well in England but very badly in Scotland. That success south of the border would then be used – leveraged, if you like – by Salmond to substantiate his claim that Scotland and England should no longer share a country.

Well, Ukip did well enough in England. But they did just a little bit too well in Scotland. True, their level of Scottish support lags some way behind their support in England but you can no longer say their Caledonian support is entirely negligible or credibly maintain there’s no place for UKIP in Scotland.

(There are many reasons why Ukip’s support in Scotland lags behind their support elsewhere but one – among several – is that in Scotland there’s already a nationalist party for people who think the Tories and Labour are just the same).

According to Salmond, however, it is all the fault of the beastly media. If the press hadn’t paid so much attention to Ukip none of this would have happened. Blaming the press, of course, is a sure sign a politician has nothing sensible to say.

But, hey, perhaps this is why the SNP’s campaign was in large part obsessed with Ukip. ‘Vote SNP to keep Scotland Ukip-free’ was pretty much all one heard from the nationalists in the campaign’s latter days. So perhaps Mr Salmond should be blamed for Ukip’s success too.

I don’t suppose the glee with which Unionists have greeted Ukip’s Scottish success is terribly edifying. But it is understandable. Unionists have been on the defensive for many months now and needed to catch a break. Nigel Farage has given them just that.

And, of course, in some respects Ukip’s success should not be terribly surprising. A third of Scots say they wish to leave the European Union (though it is a less salient issue in Scotland than elsewhere) and two thirds favour restricting immigration much more sharply than is presently the case. In terms of policy preferences (as opposed to political identification) Scotland is not so very different to England.

This is inconvenient for the nationalists but there you have it. Improbable as it may seem, this has been the Union’s best few days in a long, long time.

Ukip are awful but, gosh, they can be rather useful too. Salmond’s outrage – bluster, if you like – tells you that. The SNP won the election but in a larger sense they lost it too. Such is the fine line between success and failure.

Comments