‘Cela me revolte,’ wrote Queen Victoria in her diary in 1894 when her adored granddaughter Alexandra of Hesse announced her engagement to the Tsarevich Nicholas, ‘to feel that she has been taken possession of and carried away by those Russians.’

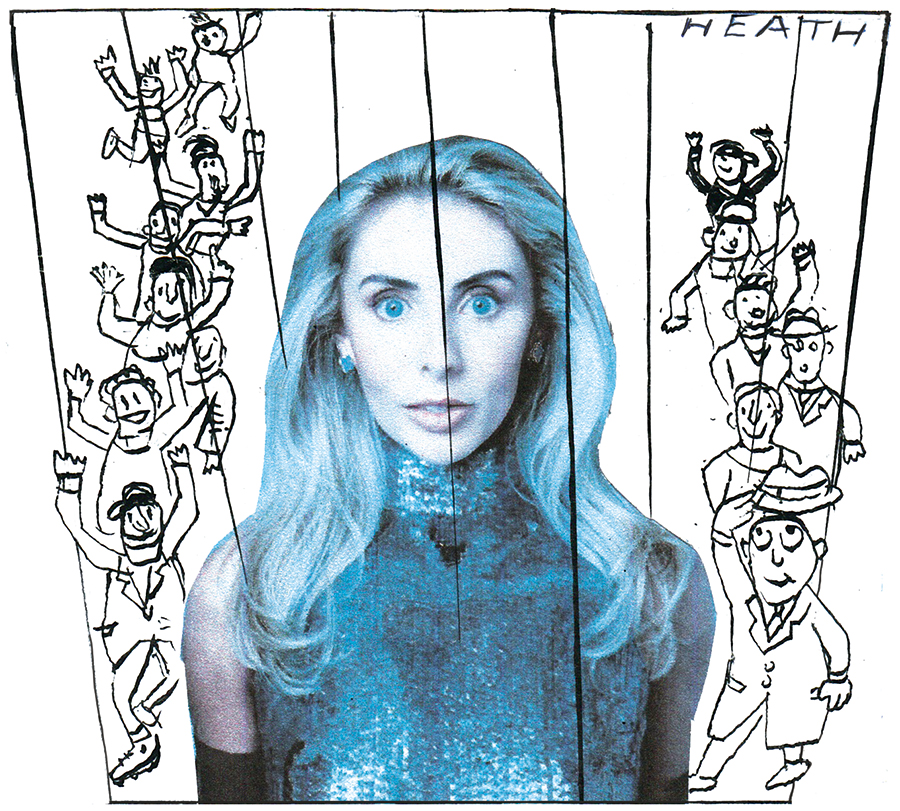

The sisters all look alike in the photos: uncomfortable dress, priceless jewellery, grimace, hair in bun

The queen was proprietorial about the four surviving daughters of her late daughter Alice, who had died of diphtheria, aged 35, when little Alix was only six. To lose one of those granddaughters to the Russians had been bad enough. Alix’s elder sister, the headstrong Elizabeth, known as Ella, had refused Victoria’s suggestion that she marry the eligible Fritz von Baden and had insisted on the corset-wearing, Dante-reading Russian Grand Duke Serge instead. And now Alix, also going against her grandmother’s advice, had accepted the proposal of the future Tsar – for which Ella was partly to blame. She’d enticed her younger sister to Russia, wanting to have her living near her.

In hindsight, we know Queen Victoria was right to be deeply worried. Both Alix and Ella would die appalling deaths at the hands of revolutionaries. Alix, her husband and their five children were shot in 1917 in a murder orgy that lasted for 20 minutes; and the following year, Ella (who was by then a widow and a nun) was thrown down a mineshaft into which grenades were then lobbed.

Frances Welch has a gift for bringing royal figures (who all look rather alike in the photos – uncomfortable dress, priceless jewellery, grimace, hair in bun) to life, making us care about them and showing us how their stories interweave. For anyone who seeks Queen Mary’s famed encyclopaedic knowledge of ‘How They [European royal family members] Were Related’ in the early 20th century, this is both a deeply affecting story of four sisters and an informative bit of history.

Victoria, the eldest of the four girls, married Grand Duke Louis, also of Hesse, who (though born in Germany) was a member of the Royal Navy until forced to resign when the first world war broke out. She would become the mother of Louis Mountbatten, and (through her daughter Alice) the grandmother of Prince Philip. After a wedding day marred by a lobster-induced stomach upset and a sprained ankle from running over a coal scuttle, she went on to have a happy marriage – although she and her husband would be stripped of their German-sounding titles. Victoria would die in 1950, aged 87, as the dowager Marchioness of Milford Haven.

Described by Chips Channon as ‘garrulous to the point of madness’, she was in fact the sensible sister and the best at keeping in touch with the others. When her daughter Alice became a religious obsessive in the mid-1930s and had to be ‘involuntarily committed’ to an asylum in Switzerland, Victoria was the one who bought Philip’s school uniform, and was the only family member to visit him at Gordonstoun.

Irène, the plain third sister, married Prince Henry, the Kaiser’s brother (Queen Victoria’s grandson and Irène’s first cousin), and they lived at the centre of the Prussian court. One of their sons, Heinrich, would die, aged four, of haemophilia after a fall. Prince Henry, who was in the imperial German navy, blithely asserted that ‘the King of England will never go to war’ – a prediction he came to rue. Irène would soon find herself in political conflict with all of her three sisters.

Ella was the one I most cared about in this extraordinary tangle of royal siblings, all of whom were assaulted at various moments by sudden tragedies. (For example, Victoria’s pregnant grandchild Cecile, along with her husband and their two small sons, would die in a plane crash in 1937.) The childless Ella was widowed when Grand Duke Serge was killed by a terrorist bomb in 1905 within the walls of the Kremlin. She visited her husband’s assassin in prison and became increasingly spiritual, rising at 1 a.m. for Orthodox matins. She also founded a religious community and hospital in Moscow, the Martha and Mary Convent, which tended to wounded soldiers. The nuns’ grey habits with long veils were designed by the Parisian couturier Mme Paquin.

Both Ella and Alix were detested by swathes of the Russian populace for being of German birth, and Ella was suspected of hiding Germans in her convent. Alix was also disliked for being haughty and in thrall to the creepy holy man Rasputin. Ella begged Alix to send Rasputin to Siberia, but she refused, causing a rift between them.

The accounts of these sisters’ deaths are extremely harrowing. Alix’s final diary entry – ‘Played bezique with Nicholas. 10.30 to bed. 15 degrees’ – shows that she was in denial about what awaited her and her children. A part of her still believed what she’d written to the worried Queen Victoria in the late 1890s: ‘You are mistaken, my dear grand-mama. Here we do not need to earn the love of the people. The Russian people revere their tsars as divine beings.’

Next time I go to evensong at Westminster Abbey I’ll look again at the sculptures of 20th-century martyrs on the West Door. The good, kind nun Ella is among them, alongside other heroes such as Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Martin Luther King.

Comments