A more appropriate subtitle to this homage to the queen bees of the interwar years might have been ‘How to Suck Up in Society’, for the servility of these six stately galleons simply beggars belief. Each was a mistress of her art, but the oiliest of the lot has to be Mrs Ronnie Greville, the illegitimate spawn of a Scottish distiller who was described by Harold Nicolson as ‘a great fat slug filled with venom’. By offering to bequeath her house, Polesdon Lacey, to the stammering Prince Albert, Mrs Greville kept the monarchy buzzing around her hive for years to come.

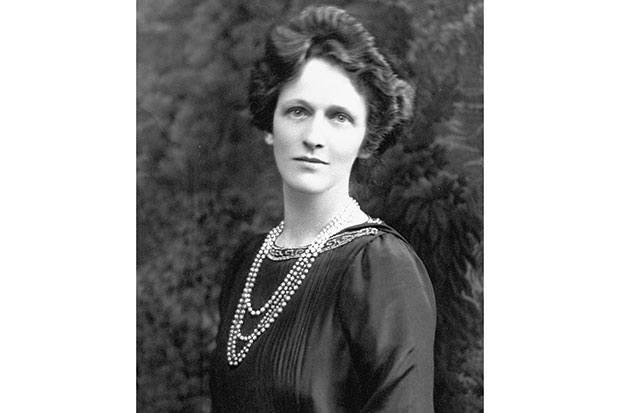

Queen Bees is a sticky blend of anecdote and social history, in which Sian Evans makes exaggerated claims for the historical significance of her salonnières. These, apart from Mrs Greville, comprise Nancy Astor, first woman MP and mistress of Cliveden; Emerald (née Maud) Cunard, champion of the conductor Thomas Beecham and intimate of Wallis Simpson; Lady Edith Londonderry, grandmother of Annabel Goldsmith; Sybil Colefax, interior decorator; and Laura Mae Corrigan, ‘humble’ Cleveland waitress turned wife of a steel millionaire.

Ambitious, competitive and snobbish to the bone marrow, each woman, says Evans, exercised a ‘profound effect on British history’ and helped bring about ‘social revolution’, be it through her response to the abdication crisis (‘How could he do this to me?’ wailed Emerald when Edward VIII blew her chances of becoming lady in waiting) or to the Munich agreement (Mrs Greville, Lady Londonderry and Emerald Cunard were enthusiasts for Hitler, and Nancy Astor — ‘the Member for Berlin’ — was pro-appeasement).

Evidently more concerned with self-advancement than social change, the rivalries between the hostesses were a source of constant amusement. Mrs Greville claimed that she was ‘never hungry enough’ to dine with crude Mrs Corrigan; Mrs Colefax and Mrs Corrigan competed over access to Mrs Simpson, while Lady Astor blamed Lady Cunard for encouraging the pro-Nazi leanings of Edward and Wallis.

It’s hard to share Evans’s fondness for her subjects, who seem less ‘brilliant and extraordinary’ than silly and entitled. Today, Evans suggests, they would have been high-ranking executives, which is possibly true. Or they might have been bored wives with rich husbands. Only Nancy Astor and Sibyl Colefax channelled their considerable energies into work; the others, apart from some character-building years between 1939 and 1945, when they pawned jewels and organised committees, spent their time composing guest-lists with poetic concentration, honing away until the line-endings were perfect.

Together they covered the market: while the Cunard coterie was peopled by musicians and dancers, Sybil Colefax procured the literary lions of the day (her Chelsea home was dubbed the Lions’ Corner House), Nancy Astor entertained the politicians and Mrs Greville had foreign ambassadors believe that the will of the nation resided in herself alone, while Laura Corrigan, who liked to stand on her head (an act commemorated in Noël Coward’s song ‘I Went to a Marvellous Party’), preferred the company of Bright Young People to dull old buffers.

The prize for the most socially desperate goes to Sybil Colefax, who was satirised by Mary Borden, in a story called ‘To Meet Jesus Christ’, as a hostess who invites her guests to mingle with the Messiah. The butt of everyone’s jokes, Sybil responded enthusiastically to an invitation to ‘meet the P of W’, who turned out to be the Provost of Worcester College. Not all the anecdotes recounted in these pages have maintained a similar freshness. Duff Cooper’s shocked account of calling at Cavendish Square to find Nancy Cunard, Emerald’s daughter, ‘suffering from a colossal hangover and still in her nightgown’, has lost its punch.

Rather than dividing the book into individual chapters devoted to the life and times of each hostess, Evans deals with them as a group in chapters which begin with the Edwardian summer, the Great War, the Roaring Twenties and end with the Thirties — Auden’s ‘low, dishonest decade’ — the second world war and austerity. Her purpose is to place the age of the chatelaine in its shifting historical context, but the effect is confusing, queen bees being hard to distinguish in a swarm.

In an act of surprising open-handedness, Mrs Greville eventually donated Polesdon Lacey to the National Trust rather than the royal family, but it is Emerald Cunard who claims the last word, by providing us with quite the best last word. Lying semi-conscious on her death bed, she muttered something that sounded at first like ‘pain’, but turned out to be ‘champagne’.

Comments