When the contestants were lining up for last night’s sensational 5,000 metre race, both of the American contestants waited until the cameras were on them, then crossed themselves and held their hands in prayer. It’s quite some sight to secular Brits, where religious language (even ‘God bless’) and mannerisms have dropped out of our national life and vocabulary. But to quite a few of the Olympians, their faith is of crucial importance, which we have seen this year through their Twitter feeds.

Mo Farah, a Muslim, prayed on the track after winning both of his Golds. After Usain Bolt broke the Olympic record for the 100 metres, he did likewise. ‘I want to thank GOD for everything he has done for me cause without him none of this wouldn’t be possible,’ he tweeted. ‘A lot a thanks goes out to the greatest coach ever. Glen Mills. Really blessed the day the heavenly Father brought you in my life.’ When the American hurdler Lolo Jones arrived London, for another attempt at the Gold, she tweeted: ‘Thank you Lord for another chance and for holding me as I waited’. On receiving this year’s Eric Liddell award British Olympic rower, Debbie Flood, declared: ‘God has given me the gifts and abilities that I have and I have tried to use them to the best of my ability.’ Muslim Olympians have been observing Ramadan and praying together. And when the Egyptian Alaaeldin Abouelkassem won a fencing silver, he knelt and prayed.

I haven’t watched all of the BBC’s Olympic coverage, but I suspect that they have not devoted much time, if any, to examining the role of religion as a motivating factor for our sportsmen. And, to be fair to them, there’s hardly a huge mass demand in a Britain, which is now, by some measures, the least religious country in Europe. The best-ever film about religion and athletics, Chariots of Fire, was British. ‘God made me for me reason, but He also made me fast,’ Eric Liddell says in the film. ‘And when I run, I can feel His pleasure.’ Even in 1984 it sounded a little anachronistic, as if athletes don’t really see the world in this way anymore.

It certainly is not a point that will be made much by commentators. But the tweets and public displays of thanksgiving, most spectacularly Mo Farah’s, show how keen many Olympians are to make this point themselves.

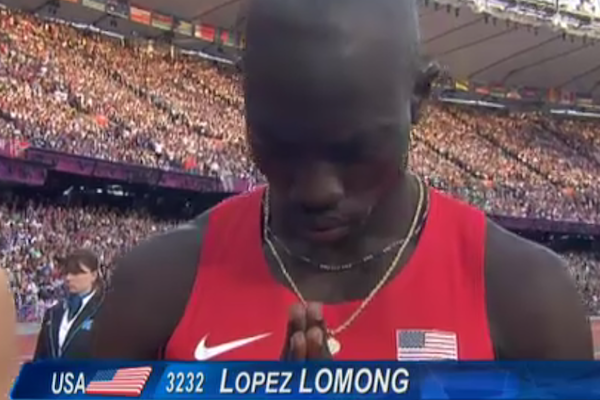

PS: The athlete pictured above, Lopez Lomong, is a Sudanese born Catholic. He was abducted at the age of six by government-backed militia while attending Mass in his home village of Kimotong. He was imprisoned with 100 other boys, many of whom perished in a war that was to kill two million. But one night he escaped, aided by older teenagers, and found his way to a Kenyan refugee camp where he grew up. He watched Michael Johnson run in the 2000 Olympics on a black & white TV and decided he wanted to run. There were not many training facilities at the refugee camp (nicknamed Lomong, after which he named himself), but a Catholic charity moved him to America when he turned 16. Last night, he stood in front of the world’s cameras in the final of the 5,000 metres. If he looked like he was giving thanks, that’s probably why.

Comments