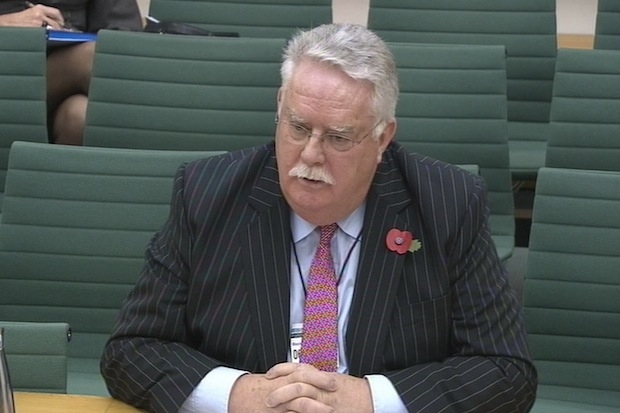

There has naturally been plenty of unfavourable comment on how the Revd Paul Flowers, the ‘crystal Methodist’, was allowed by the Financial Services Authority to become chairman of the Co-op Bank. But the story does not reflect very well on the media either. If you look at Robert Peston’s BBC blog on the subject, for instance, there is a lot of ‘I am told’ and ‘according to the Manchester Evening News’. Is there no one in the BBC’s enormous staff who could have done a bit of work years ago on the Revd Mr Flowers? Isn’t it even more extraordinary that the media did not pick up Mr Flowers’s ignorant testimony earlier this month to the Treasury select committee until it was drawn to their attention on Sunday after he was exposed by the Mail on Sunday for buying illegal drugs? It seems truer than ever that the only way to ensure no one notices you is to say something publicly within the Palace of Westminster. Like Falkirk and Grangemouth (see last week’s Notes), this is a story about the inner workings of the Labour movement. It is grimy in its details. It may even require leaving London and going somewhere in the north to discover the facts. I suppose that is too much to ask. But if it had been a story about Tory corruption of a bank, I feel Mr Peston and co would have been in more of a hurry to find out about it.

As the Warsaw Climate Change Conference meets, it is becoming apparent that bolder, freer countries are undermining the principles which green visionaries wish to inflict upon the world. Japan is allowing itself more carbon emissions, pleading the effects of Fukushima. Canada and the new government in Australia are ceasing to make more than perfunctory obeisance to the god of global warming. This leaves countries like Britain terribly exposed. David Cameron can see that his endorsement early in his leadership of ever-higher energy bills is an election-losing mechanism brilliantly targeted at poorer voters, but he feels he cannot say so. His fixed-term parliament act means that he must spend the next 18 months watching competitiveness leave our shores, heading both east and west.

Lady Antonia Fraser tells me that she gave my biography of Margaret Thatcher as a birthday present to her son Damian. She posted it to him in Mexico, where he lives. For a very long time, however, it did not arrive. It turned out that the book’s considerable weight had attracted the attention of the Mexican customs officials, who suspected it of containing drugs, and submitted it to intimate body searches. I feel bucked by the idea that anyone could have thought my book might have a street value of $1 million.

The relationship between the Queen and Mrs Thatcher is one of inexhaustible public interest. I am constantly being asked about it. It is wrongly and unconvincingly presented in a scene in the immensely popular The Audience. Last week, I went to see Handbagged, an entire play devoted to the subject, at the Tricycle Theatre in Kilburn. It is boring, inaccurate and self-righteous, and has an irritating device by which both the Queen and Mrs Thatcher have alter egos, so characters call Q, T, Liz and Mags mill about confusingly on stage. The play is remarkable, however, for the fact Fenella Woolgar, who acts Mags, gives the first really convincing stage representation of Mrs T. She captures her unusual way of speaking in which words were generally pronounced with great clarity but occasionally swallowed in the desire to increase their productivity. She also conveys the genuine femininity, which others, preoccupied by conveying harshness, neglect. As Meryl Streep has also shown, some actresses are well capable of interesting themselves in the reality of Margaret Thatcher rather than the cardboard cutout on which to hang dreary political points. Oh for more dramatists of whom one could say the same.

The whole fascination of the Queen as a dramatic subject depends on the fact that she does not directly speak her mind. As soon as dramatists forget this, and put into her mouth what they would like her thoughts to be, all humour, tension and believability perish as though they had never been.

This column recently complained (19 October) that the government’s pretence of taking press regulation out of politics by using the device of Royal Charter has the unintended effect of dragging the monarchy into politics. This week, the Press Complaints Commission found against the Guardian (a fact I could not find recorded in the print version the following day). The paper had claimed that the Queen’s private secretary, Sir Christopher Geidt, was unsuitable to be ‘one of the final arbiters of press regulation’ since he had tried to suppress John Pilger when he alleged that Geidt had assisted the murderous Khmer Rouge in Cambodia in the late 1980s. There were two flaws to this story. The first is that, as even the famously truth-challenged Pilger had to acknowledge in open court in 1991, Geidt had nothing whatever to do with helping the Khmer Rouge. The second was that, in his present job, he has nothing whatever to do with press regulation.

The Netherlands, which I recently visited, is perhaps the only country whose monarchy is as popular as ours. What the Dutch monarch can do politically is even more curtailed than our own, which may explain why the new King, Willem-Alexander, is still an airline pilot. His Majesty puts in the hours required to maintain his licence by flying KLM Cityhopper’s Fokker 70s. For this purpose, he works under one of his least known titles, ‘W.A. van Buren’. It shows how calm and sensible the Dutch are that this can happen. Imagine if the Duke of Cambridge took his turn in the BA cockpit, disguised as William Carrickfergus. How the twerpy snappers, the stag-party drunks, the Tweeters and Facebookers, the Islamist terrorists, and the representatives of my own dear trade would start creating in-flight turbulence.

Comments