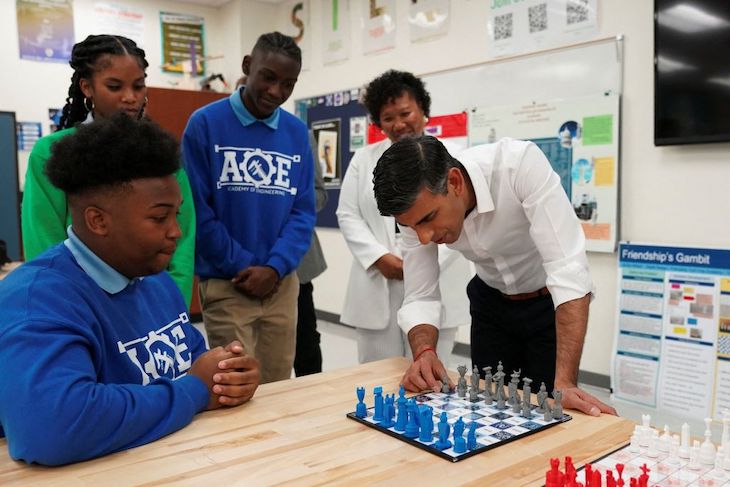

There’s something embarrassing about Rishi Sunak’s plan to revive chess in Britain. The PM is set to announce half-a-million pounds funding for the English Chess Federation. The money could be used to send teams to international tournaments, install chess tables in parks and teach the game to school kids. But Rishi’s cheesy cheerleading for government-sponsored chess is reminding me a lot of a parent buying condoms for their teenager: there’s no better way to take the sexiness out of sex.

Perhaps the PM is trying to take inspiration from eastern Europe. Last October, I went to Budapest to interview the world’s best-ever female chess player, Judit Polgar, and also attended the chess festival she hosts at the Hungarian National Museum in Budapest. There, I met the then-Georgian minister for education, Mikheil Chkhenkeli, who was proud about having just introduced mandatory chess playing for six-year-olds in school, joining only Armenia in making the game compulsory for school children.

Rishi sounds like he is trying to keep up. But Armenia and Georgia are poor countries, formerly in the Soviet Union, and there’s nothing stopping them, at least culturally, from state interference in anything they fancy.

For Rishi, however, it’s an embarrassing bit of fiddling. A game like chess, with boards that cost next to nothing or literally nothing for the majority of players who are on chess.com, or who drop in to one of Britain’s thousands of regional chess clubs, there is absolutely no need for government assistance. It’s just a dirt-cheap way for Rishi to appear to be thinking ‘creatively’ about education. But it really is none of his business who plays chess and when, or where. There’s also no better way to put people off one of the most cerebral, beautiful and accessible games there is than to get Whitehall involved.

It’s an embarrassing bit of fiddling

Chess is already an incredibly democratic game. At the Greater London Chess Club, which meets in St George’s on Little Russell Street in Bloomsbury on Tuesdays during the season – a locale in which I passed many a rainy winter’s night this year – the crowd includes the homeless; hoodie-wearing teenagers, and sundry working class chess-heads of all skin colours. This year’s reigning club champion – my mentor – is a security guard who used to be in the army. Yes, there’s also a fair batch of European software programmers and British geneticists.

The government is looking to take credit for something that is already happening. The interest in chess among young people, from children to the dreaded Gen-Z, is already high and growing. Since January 2020, more than 102 million users have signed up to chess.com; a 238 per cent increase. In schools, teachers have been flummoxed by mass distraction in classrooms as pupils pore over their chess apps, inspired by the rise of chess influencers like Anna Cramling and Anish Giri.

The only real problem is that it’s still mostly boys and men who dominate chess, though that is changing; Netflix’s The Queen’s Gambit nudged up female sign-ups to chess.com by 15 per cent and countries like India are producing many fantastic girl masters, like Shaarvanica (the Madonna of seven-year old chess champs). In Britain, female participation is still woeful: I was the only woman at the club most of the time, even though it was a perfectly welcoming environment. We need more girls in chess fast if we are to stem that tiresome rhetoric about how our brains are just less rigged for logic. I didn’t see anything in Rishi’s trumpet-fanfare about girls, though.

To be sure, any society in which everyone played chess would be at an advantage. Chess is an astonishingly insightful game. If you can get good at it, you are essentially cultivating a ruthless set of logic skills. Even if you stay terrible at it, like I have, there is much to learn: the extent of one’s cognitive biases, how difficult it is to engage with reality (chess is nothing if not nakedly, relentlessly true), how little one sees of any given situation at any one time. It’s social in a wonderful way: I have found much joy in the open and friendly games, tutelage and encouragement from the most unlikely of people: mostly chess-geek men at the club ranging from 16 to 60. Online, it’s reconnected me with long-lost friends, male and female, in a forum that isn’t all about banal bantz (which tends to fade, in comparison to the addiction of chess). And it is a proper distraction, unlike just scrolling endlessly through Instagram.

Chess for all, yes. Chess for all sponsored by the British government? That would be a blunder.

Comments