One advantage to being born in the 1970s was the sheer abundance of good kids’ TV on offer. This was the golden age between clunky black and white offerings like Muffin the Mule, and the creeping vapidity of later shows like Teletubbies or The Care Bears. It gave us Camberwick Green, The Magic Roundabout, Captain Pugwash, Mister Benn (and the Mister Men), The Clangers, Playaway, Hector’s House, Fingerbobs, Tiswas, The Muppet Show, Ivor the Engine, and Basil Brush – not forgetting the holy trinity of Mary, Mungo and Midge.

Did we hit the jackpot, or what? As my daughter, aged 11, prepares to leave her own childhood, I’ve been rewatching a few of them. The first is Pipkins – the pre-lunch show by ATV that ran from 1973 to 1981 and gave us the antics of a hare, a pig, a monkey and a tortoise (not forgetting Octavia the Ostrich), all sharing an urban house together. In 15 minutes or so, the show gave you plenty: jokes, a song, a poem, a playlet, and lots of horseplay between the characters. But best of all, you got Hartley Hare. Hartley, with his posh, prissy delivery and frequent asides to camera, was gossipy, witty, grandiose, self-pitying, egocentric, flirtatious, backstabbing and utterly beguiling. Voiced by Nigel Plaskitt, he was probably the juiciest personality on children’s TV (with only Basil Brush for competition) and a preparation for characters later on, when you were older, like Richard E. Grant’s Withnail or Rik in The Young Ones – both of whom Hartley more than a little resembled.

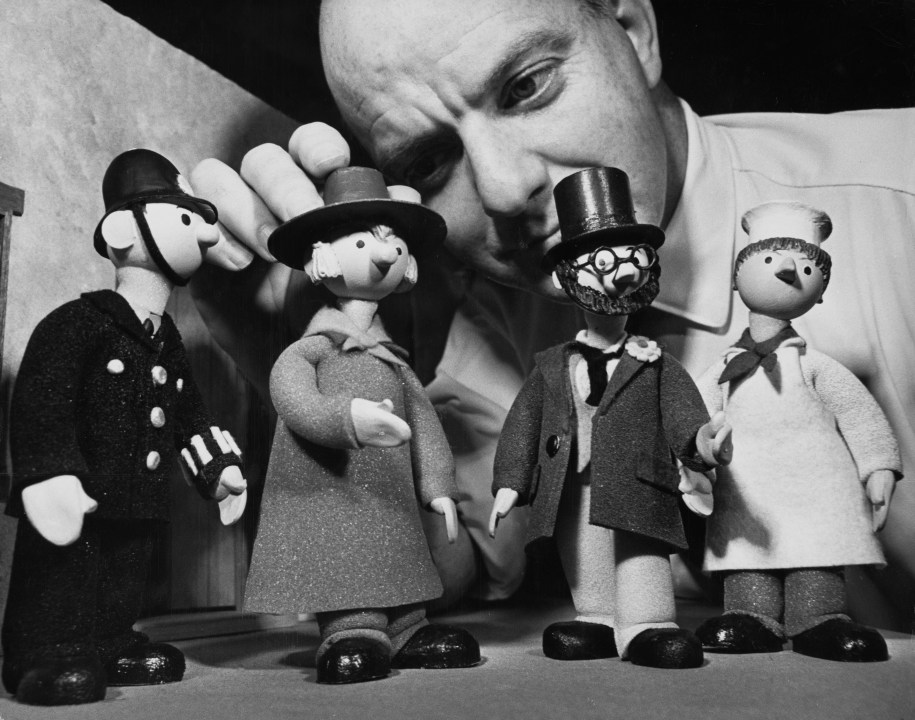

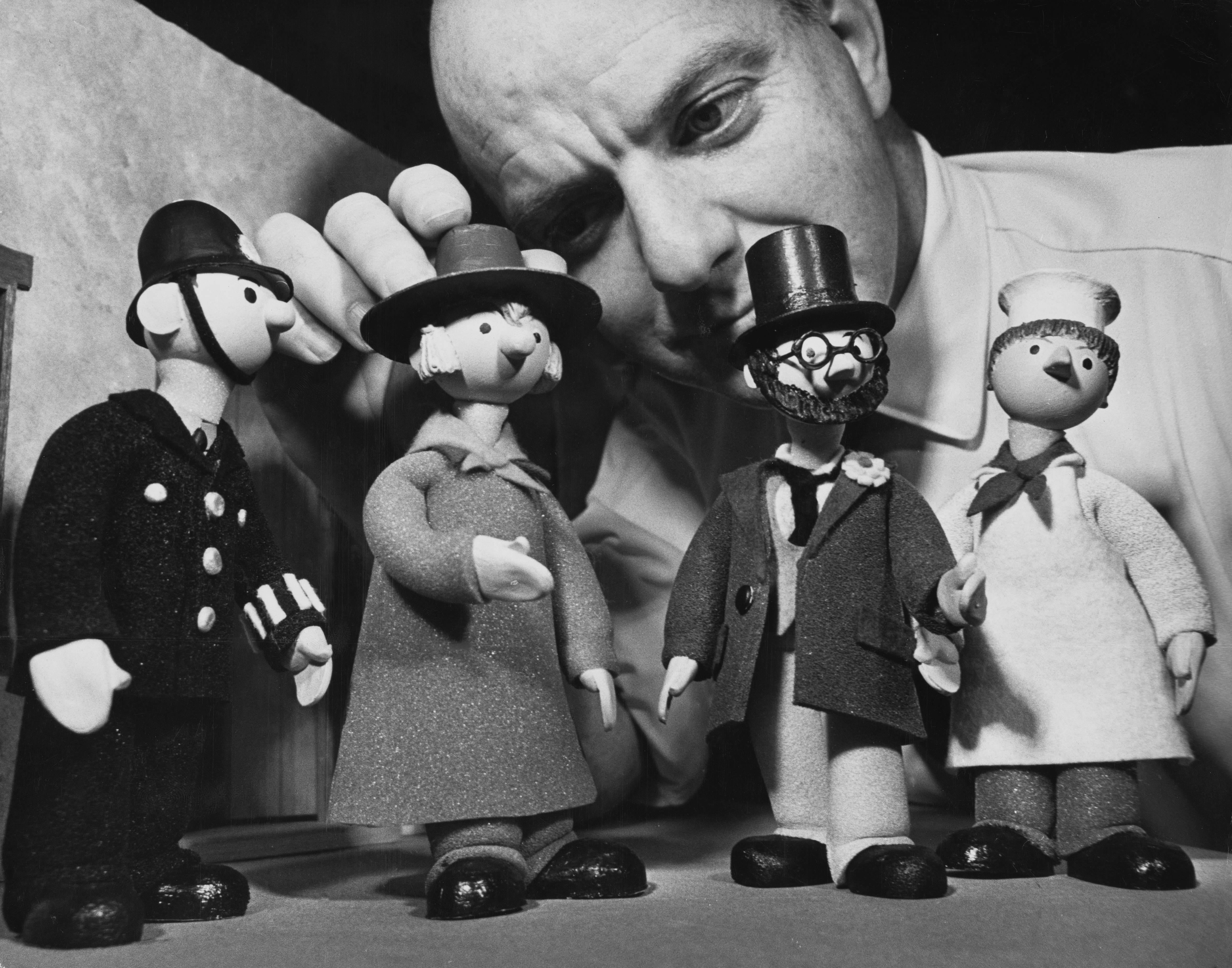

Then of course there were Gordon Murray’s Camberwick Green and Trumpton, which stay with you throughout life (though through my adult eyes the second seems more rollicking). A generation (or generations, if you count the repeats and DVDs) grew up with those strangely mouthless, stop-motion characters like Windy Miller, Doctor Mopp and Mrs Honeyman (the village gossip), and got used to places like Mr Munnings’s print shop and the military Pippin Fort. They saw a well-ordered, functioning community, with everyone snugly in their place – polite, looking out for each other, keeping a respectful distance (even if neither series could decide, to judge from the costumes and vehicles, whether it was set in the modern or Edwardian age).

No real aggro entered this world: a postman’s sack snagged on a windmill’s sail, a mayor’s hat got stuck up a tree, and it was all quite dramatic enough for a child. Along with Trumpton’s wonderfully rhythmical roll call of firemen – ‘Pugh! Pugh! Barney McGrew! Cuthbert! Dibble! Grub!’ – the two series had catchy tunes and song lyrics, usually backed by a classical guitar (an instrument having a field day in the early 1970s). All was helped along by narrator Brian Cant, chosen by Murray – writer Tim Worthington tells us in his splendid Golden Age of Children’s TV – because he sounded like a ‘storytelling young father’.

But the programme that really haunts me (and probably you) is Oliver Postgate’s Bagpuss, a show as original as its creator. Postgate grew up staggeringly well connected: his father was the food critic Raymond Postgate, his grandfather Labour leader George Lansbury, his uncle the economist G.D.H. Cole – though it didn’t help him much. Initially, he seems to have been a jack-of-all-trades: aspiring inventor, toy designer, button manufacturer, failed writer, failed artist, failed actor. But it was when he wrote a children’s programme for Associated-Rediffusion (the forgotten Alexander the Mouse) and subsequently discovered stop-motion photography that his career really took off: ‘My body, which always understood much better what was going on than my head, was dancing about, sending up waves of idiotic delight and conjecture. “This way,” it shouted, “you could make whole worlds, complete places full of people, and with your love you can give them life!”’

He duly did so – creating Ivor the Engine, Noggin the Nog, The Clangers – but Bagpuss was his masterpiece. Filmed in a Kent barn, with puppets and sets designed by collaborator Peter Firmin, the series took place in an old antiques shop belonging, inexplicably, to a little girl named Emily (played in the sepia photographs at the beginning by Firmin’s youngest daughter). Apart from its pink and white title character – ‘the most important, the most beautiful, the most magical saggy old cloth cat in the whole wide world’ – it featured a chorus of chirruping, loveable mice, and a pompous old woodpecker called Professor Yaffel (based, Postgate said, on G.D.H. Cole and Bertrand Russell). Making up the cast were a rag doll called Madeleine and a banjo-playing toad, voiced by folk duo John Faulkner and Sandra Kerr.

In some part of us Windy Miller is still grinding his grain, Bagpuss stretching awake with a technicolour yawn

The episodes are beautifully written and narrated by Postgate, each revolving around an object Emily has found and which, in the process of restoration, the animals tell fantastical tales about. Though as English as the folk songs and Edward Lear-like poetry that fill the 15 minutes, Bagpuss seems, in its surreal, echoing inventiveness, to have hints of Central Europe as well (the Hungarians and Czechs – not least Jan Švankmajer – were doing wonderful things in stop motion at the time).

While Bagpuss was openly concerned with preserving old items – at a time when so many historic British buildings had just been demolished under the Wilson government – there was nothing preachy about it, no overarching will to proselytise or socially engineer. ‘The pottiness of political correctness,’ Postgate later wrote, ‘had not yet infected our thinking.’ Instead, he and Firmin asked themselves three questions: ‘Did we enjoy it? Did we think children would enjoy it? Did we think grown-ups would like it?’ As a result, Bagpuss is still triumphant, in 1999 coming first in a BBC poll to find which of their kids’ programmes the nation held most dear.

Watching these shows again, I can trace things in my adult self right back to them: a love of reclaiming discarded things (Bagpuss), a fondness for marionettes and hand-painted wooden boxes (Camberwick Green), or buildings that harbour, behind anonymous facades, vivid unexpected worlds (Mister Benn). One Spectator colleague even attributed his adult conservatism to Trumpton – it gave him, he said, a model of what a happy civic society could (and should) be.

My generation was lucky: in these series we got good teachers, and like the real kind, you never forgot them. In some part of us Windy Miller is still grinding his grain, Bagpuss stretching awake with a technicolour yawn, and Trumpton’s mayor, fully robed, is skiving off to feed the ducks in the park – even if Emily’s shop has now moved onto eBay, Mister Benn these days goes to swingers’ parties, and Munnings the printer has switched to selling vapes.

We still have the shows. In his extraordinary autobiography Seeing Things, Oliver Postgate conjured up warm moments from his own childhood, recalling the days he was ill and his parents let him rest in their luxurious double bed. There, he said, he would ‘lie in splendour… float in absolute happiness, knowing that I was in the safe centre of life.’ With their creations, the likes of Postgate, Gordon Murray and their contemporaries allowed generations of us children to feel the same way, and we owe them, as adults, an incalculable debt.

Comments