China’s naked weaponisation of rare earths brings to mind Mao Zedong’s ‘four pests’ campaign, the old tyrant’s fanatical effort to exterminate all flies, mosquitoes, rats and sparrows, which turned into a spectacular piece of self-harm.

Sparrows were always an odd choice of enemy, but Mao and his communist advisers reckoned each one ate four pounds of grain a year and a million dead sparrows would free up food for 60,000 people. The campaign, launched in 1958, saw the extermination of a billion sparrows, driving them to the brink of extinction. But the sparrows also ate insects, notably locusts, whose population exploded, and the ravenous locusts wreaked far more damage to crops than the sparrows ever did, hastening China’s descent into the deadliest famine in human history.

It’s hard not to conclude that western democracies sleepwalked into this crisis

Nobody is expecting a repeat of that tragedy. But the rare earth controls threatened by Beijing, which could cripple advanced western economies, could and should backfire if they finally open western eyes to the need to urgently address dangerous dependencies on China.

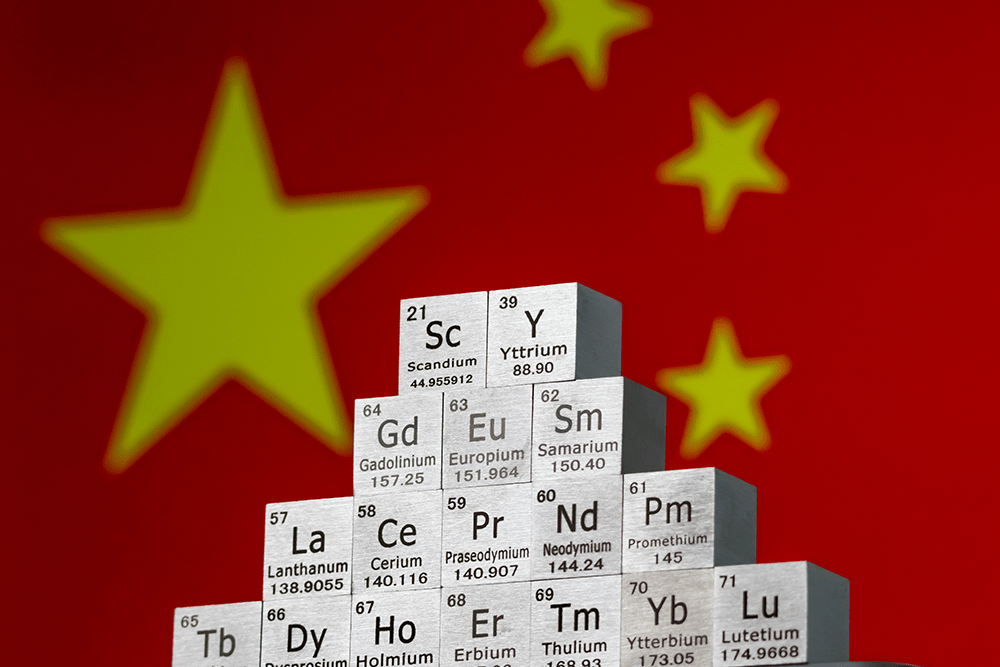

Rare earths are a group of 17 elements, until recently little known beyond the chemistry lab, but vital to hi-tech industries ranging from fighter jets, submarines and satellites to mobile phones, electric vehicles, wind turbines and batteries. China controls 61 per cent of the world’s mining and 92 per cent of refining, according to the International Energy Agency.

In an interview last weekend with CBS News’s 60 Minutes, Donald Trump said of the rare earth threat: ‘That’s gone. Completely gone.’ He explained that his moves to impose an additional 100 per cent tariff forced Xi Jinping to back down. In fact, his summit with Xi in South Korea produced a truce at best, and the rare earth controls are merely on hold. It’s a shaky agreement. Later in his interview, Trump claimed he had secured a window to build US (and global) resilience: ‘This was really a threat against the world. So the whole world has come together, I think, at our behest. And rare earths, within two years, rare earths will really cease to be a problem.’

Sweeping new export controls would have required any company that wants to supply rare earths produced in China or which are processed with Chinese technologies – even outside China – to obtain a licence from the Chinese government, giving the Chinese Communist party a veto over who uses them and how they are used.

The dirty little secret about rare earths is that they are not so rare; they are found throughout the world, including in the US, Brazil, Australia, Vietnam, India, Greenland and Canada. Even Britain has small deposits. It is in refining – a filthy business – where China has the greatest edge, and where it tolerates high levels of environmental degradation. Washington is now scouring the globe for alternative supplies, signing deals with Japan and Australia among others.

The European Union has vowed to break dependencies on Beijing. The European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has warned of a ‘clear acceleration and escalation in the way interdependencies are leveraged and weaponised’. Canada has announced a flurry of investments and partnerships, and Turkey has touted the discovery of potentially vast reserves.

In his 60 Minutes interview, Trump appeared to take credit for much of this, boasting of the partnerships he was establishing ‘with Japan, with Australia, with UK, with just about everybody, frankly’. Yet his wider tariff policy is also alienating key allies. Beijing has been keen to exploit that by presenting itself as a champion of free trade, though that claim, always implausible, is being undermined globally by its aggressive exploitation of its rare earths monopoly.

It’s hard not to conclude that western democracies sleepwalked into the rare earth crisis. The CCP has long been a master of ‘war by other means’, using trade, investment and market access as means of coercion, and Beijing has made no secret of its willingness to weaponise its near monopoly.

As long ago as 2010, it slashed exports to Japan after a territorial dispute, and experts have long warned about the potential dangers. In December 2023, a scathing report from the House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee warned: ‘Successive governments have failed to recognise the importance of critical minerals to the UK economy and failed to respond adequately to the aggressive capture of large parts of the market over the last three decades by China.’

Witnesses complained their warnings were not heeded. Jeff Townsend, director of the UK Critical Minerals Association, told the committee he began raising the issue with the government in 2012 and said he had ‘been banging my head against a brick wall ever since’.

Britain, warned by China of ‘consequences’ if its proposed new mega-embassy in east London is not approved, appears to be particularly vulnerable. Rare earths are critical to the technologies of the so-called ‘green transition’. Attempts to gain a foothold in the rare earths industry – a key platform of the government’s much hyped ‘critical minerals strategy’ – collapsed last month after Pensana, a mining company, scrapped plans for a refinery near Hull. The facility was to have processed minerals from Angola, but it is instead to be built in the US, which offered more support.

China’s rare earth controls go far further than any coercive measures it has taken before. Unlike the often petulant boycotts and bans that characterised past Chinese efforts at punishing countries or companies deemed to have caused offence, China has put in place a systematic licensing system that can be calibrated and targeted at will. It framed its rare earth controls as a matter of ‘national security’, a response to US restrictions on the sale of powerful chips used for artificial intelligence, but its sweeping nature and potential to bring western hi-tech industries to a standstill go far beyond anything imposed by America.

They were also well prepared; over recent months the authorities gathered detailed information about how rare earths are used in western supply chains and restrictions have reportedly been imposed on the ability of factories in the industry to shift equipment out of the country and on the international travel of their executives.

The system may become a model for other areas where the West is dangerously dependent, from critical minerals such as lithium and cobalt, so essential to ‘green’ technology, to the tiny cellular modules that are the ‘gateway’ component for all connected devices, where China is intent on gaining a monopoly – and even pharmaceuticals, where antibiotics and other vital drugs rely on Chinese supply chains.

Beijing’s economic policy under Xi is explicitly built around the twin goals of self-reliance in technology and building dependencies on China. As Xi himself told a meeting of the Central Financial and Economic Affairs Commission in 2020: ‘We must tighten international production chains’ dependence on China, forming powerful countermeasures and deterrent capabilities based on artificially cutting off supply to foreigners.’

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the initial disruption to energy supplies is a stark lesson in the dangers of overdependence on a hostile state. The controls on rare earths, in effect holding western economies to ransom, should be a defining moment – if, that is, the right conclusions are drawn about foolhardy dependencies on China.

Comments