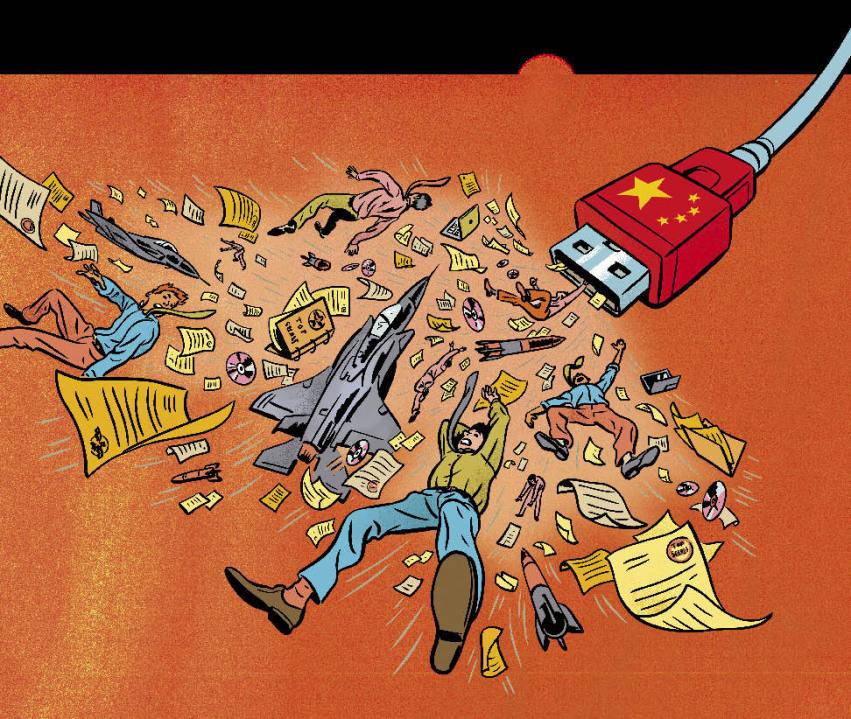

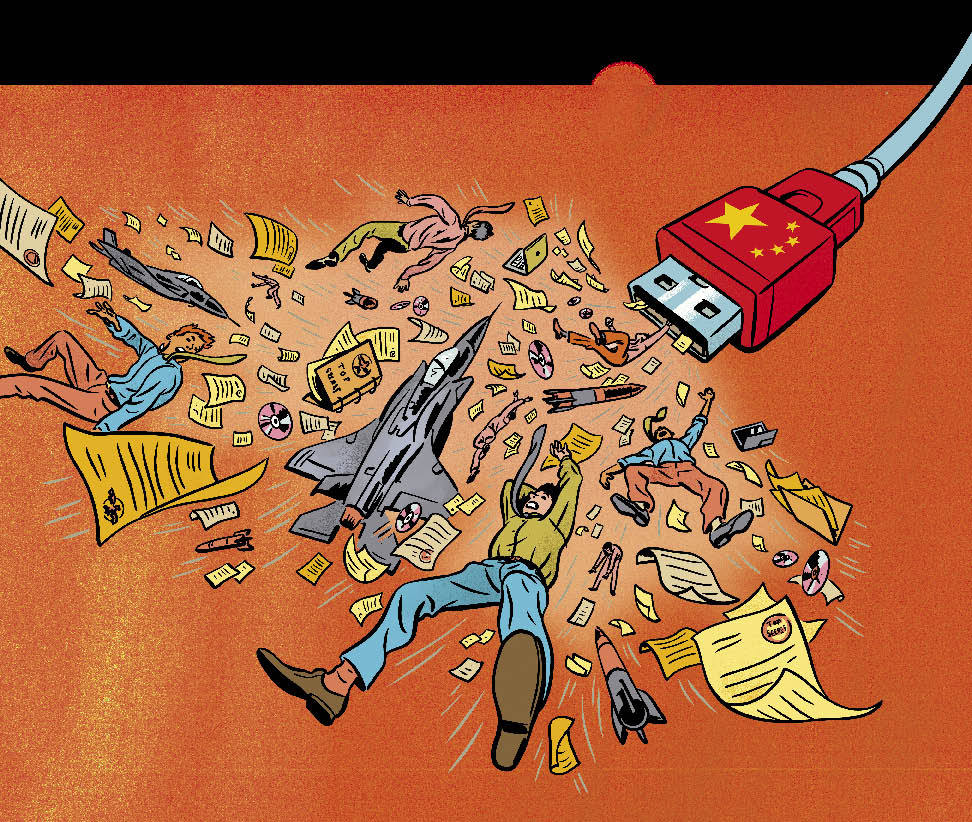

We are at war online – and we are losing

Almost exactly two years ago, an American army officer found a memory stick in a car park in the Middle East and, out of curiosity, inserted it into his military laptop. It seemed to be empty, but there are a million ways of disguising a Trojan computer virus. Instantly, a malicious software code uploaded onto the US Central Command military computer network and embedded itself in the system. And there it lay undetected for weeks, able to send back all manner of classified information. In the words of the deputy US defence secretary, William J. Lynn III, it was ‘poised to deliver operational plans into the hands of an unknown adversary’. That unknown adversary was almost certainly China.

Until recently both Britain and America flattered themselves to think that their digital secrets were safe behind fearsome layers of protection. The WikiLeaks fiasco has shown this to be laughably untrue. Just a few years ago, the act of stealing 251,000 secret documents from the Americans was beyond the imagination of fiction writers, let alone the capabilities of spies. But as technology developed, so has the potential for disaster. It seems that a 22-year-old army private in Baghdad with an appetite for mischief, together with a publicity-hungry Australian with a website, have sent the American government and defence establishment reeling.

Suddenly, the western internet ‘firewalls’ are looking like a digital Maginot Line, so vulnerable that amateur hackers can steal hundreds of thousands of secrets for fun. So what might a cyber-army be able to achieve? One answer came last year, when a Chinese software trap was found on the American National Grid, with the aim of shutting down the system entirely. Another came in April, when China hijacked 15 per cent of the world’s internet traffic — emails and data were routed through Chinese servers, where they could be copied or tampered with, and then sent on their way. There is no suggestion that China seeks to shut down the West, simply that it is testing its capabilities. And as we are finding out, all too late, they are awesome.

Cyber-warfare may sound fantastical to western ears, but is being taken deadly seriously in the East, and is seen as a domain where they have the edge. ‘What strikes me about it is the sheer blatancy of the Chinese,’ a senior defence figure tells me. ‘They know we know they’re doing it — and they don’t care.’ So far almost all the Chinese hacking appears to have been directed at British companies, especially high-end engineering ones which may have intellectual property that is useful to their Chinese rivals. But as the hackers’ skills develop, so does their ambition. The scope of the digital menace might include the ability to disable banks, turn nations’ lights off and disorientate their militaries.

Two months ago the head of MI6, Sir John Sawers, took the extraordinary step of spelling it out. ‘Attacks on government information and commercial secrets of our companies are happening all the time,’ he said. ‘Electricity grids, our banking system, anything controlled by computers could possibly be vulnerable. For some, cyber is becoming an instrument of policy as much as diplomacy or military force.’ He stopped short of naming any guilty party, but this is the devil of cyber-warfare. There is never a proper trail, never any conclusive evidence. All of the circumstantial evidence may point to China, but we just can’t prove it.

British businesses, however, can point to a pattern. ‘As soon as you strike a deal with China, your computer systems come under attack,’ says one chief executive. ‘The Australians will tell you the same thing. The Chinese try to insert Trojans in your computer systems, to send information back to Beijing.’ The aim might be to find out how much a British buyer is willing to pay, or simply if the designs for a product can be downloaded rather than bought.

Five years ago, British intelligence assessments regarded Chinese information gathering as a headache. ‘The Chinese were hoovering up everything, useful or not,’ says one senior civil servant. This was resented mainly because it diverted resources from MI5, which was then on a hunt for domestic terrorist cells. But the frequency and sophistication of the threat has increased significantly as rogue states have joined in. Three years ago Jonathan Evans, the head of MI5, wrote to the heads of 300 British companies warning that ‘Chinese state actors’ were trying to steal their intellectual property. Rolls-Royce and Shell are understood to be two early victims.

When Gordon Brown visited China two years ago, one of his advisers was approached by a local girl in a Shanghai disco and he took her back to his hotel room. When he woke up, the bird had flown — and had taken his BlackBerry with her, with all its various contact information. He was told that he’d succumbed to a classic Chinese honeytrap — the type with which businessmen are now familiar. ‘We daren’t even take our laptops into China,’ says one director of a FTSE100 bank. ‘They will swipe all the information from it at the airport.’

China’s focus so far has been on British engineering and defence companies: after all, why buy the company when you can steal its secrets for free? This may make western governments angry, but they need Chinese money too much to impose economic sanctions. So when western leaders come to Beijing, they talk trade (and leave their BlackBerries at home). It has long been the western hope that capitalism will eventually liberalise China and Russia. But both seem depressingly capable, so far, of combining state capitalism with political repression. Cyber-warfare is just the latest tool.

Britain’s latest assessment is that Russia (which is more discreet with its own cyber-spying) shares stolen company secrets with China. The Kremlin operates hand-in-glove with the oligarchs, just as China does with its exporters, and for both, corporate interest has merged with government interest. This is what has driven the hacking. British companies hire their own counter cyber-espionage networks, but still ask for government back-up. The American response was to open a digital war HQ, Cyber Command, last month. Britain recently identified cyber-warfare as one of the top four threats facing the country.

The Kremlin has so far taken the view that the oligarchs are rich enough to finance their own dirty work, and aside from passing on secrets from the Chinese, its own hacking is focused on its military priorities. During the war two years ago in South Ossetia, Georgia found its computer systems disabled as the Russians attacked. This was what is (now) seen as a crude form of cyber-attack, the so-called Denial of Service attack aimed simply at crashing the computers of banks and government agencies by inundating them with bogus requests. Estonia suffered a similar assault in a skirmish with Russia a year earlier. Even North Korea succeeded in launching a cyber-attack against the South.

Blame is attributed, but nothing is proven. The Estonian and Georgia attacks were never properly traceable, and the Kremlin suggested the culprits might have been outraged patriotic hackers. When South Korea commissioned a Vietnamese security company to investigate its attack in summer last year, the leads went back to six computers all over the world. The order to attack was traced to a computer server in Brighton.

The Cold War was written around the doctrine of mutually assured destruction: if Russia launched a missile at America, it knew there would be a return strike. ‘But if we don’t know who has hit us, how do we retaliate?’ asks a senior British defence official. ‘We do not have an answer. This makes a mockery of our rules of engagement.’ Intriguingly, there is also a question abo ut whether Britain could retaliate: whether we could, if we wanted to, turn off the lights in Beijing or disable its military computers.

Even inside government, one hears conflicting reports. Some defence officials say with a wink that Britain is far more developed in the computer hacking stakes than it would be prudent to admit. But other reports are of us playing catch-up, struggling to identify our own vulnerabilities. The Liberal Democrats are pushing to ensure that any cyber-attack launched by Britain would comply with (currently nonexistent) international law. The most eloquent comment on the gap between what Britain can do and what it needs to do is that an extra £650 million is being spent on our cyber-defences.

After all the debates about aircraft carriers and submarine hunters, the West is facing another asymmetric war — one with implications that no one yet understands. As one British minister puts it: ‘The peace around China is kept by the American Navy. But the Pacific fleet would not be much use if it doesn’t knows where it’s going.’ When there was a power failure in an American missile system recently, questions were raised in the Ministry of Defence as to whether the Chinese had made another breakthrough. The odds are that Beijing is nowhere near able to control military systems remotely — but paranoia is rife.

Both Britain and America have defence budgets and capabilities that dwarf China’s — but cyber-wars are new. Each time a virus is intercepted, it is replaced by a more sophisticated one. China develops computers very quickly. Staggeringly it takes the Pentagon, on average, six years and ten months to take delivery of a computer system that it orders. So American defence computer systems are routinely four generations behind. Little wonder they are sitting targets for computer hackers — amateur and professional alike. Britain does not release such figures, but what we know about the rest of the Ministry of Defence’s procurement is hardly encouraging.

British officials will admit the problem in public, but not our lack of preparation. American officials are open about theirs. Lynn admits in the current edition of Foreign Affairs that the defence industry and computers usually make poor partners. ‘The iPhone was developed in 24 months,’ he moans, ‘less time than it would take the Pentagon to prepare a budget and receive Congressional approval.’ He could not be more explicit: cyber-attacks offer America’s enemies — from terrorists to aspiring superpowers — a means of overcoming their overwhelming military disadvantages. And doing so in ways that are instantaneous and hard to trace.

It might all come to naught. It is likely that even the Chinese, though dazzled by the possibilities, have no serious desire to switch off the lights in London or New York. But should such technology fall into the hands of terrorist groups, or crackpots in North Korea, then all bets are off. There are few certainties in this rapidly changing field of combat. But we know that cyberwar is real; that the West is currently losing; and that no one has the faintest idea how this battle might end.

Comments