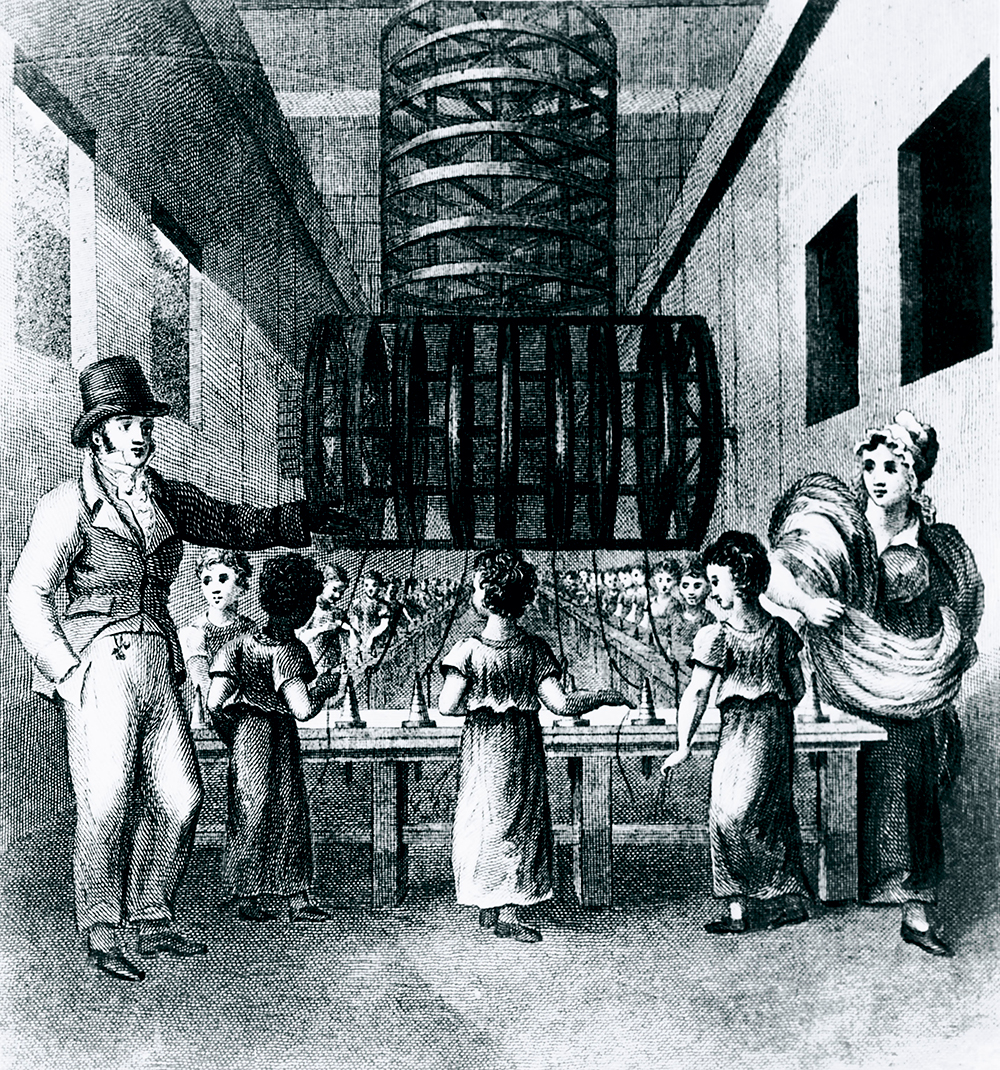

On a damp Derbyshire day in 1771, Richard Arkwright watched the world’s first water-powered mill begin to turn, setting in motion a force that would remake the world. The tailor’s son from Preston had become one of Britain’s first industrialists, his spinning frames driven by water and his workers by hunger. Within those mill walls, as Edmond Smith argues in Ruthless, the modern economy took its first breath.

Yet the real invention was not mechanical but social. Arkwright had helped pioneer the system that would propel Britain into the lead in the first Industrial Revolution – web of investors, miners, shippers and merchants, bound by credit, trust and the push for profit. In Smith’s phrase, it was ‘networked capital’, the invisible machine behind the visible one.

Smith’s case is that Britain’s industrial miracle owed less to lone genius than to the architecture of finance and connection. The historian G.M. Trevelyan once quipped that England escaped the revolutionary fate of France because its aristocrats were too busy playing cricket with their peasants. Yet the British nobility were doing more than playing games: they were growing rich by joining forces with inventors and investors, exploiting the raw materials beneath their land.

Across 18th- and 19th-century Britain, such partnerships crossed class lines to build joint stock companies and credit networks that linked foundries, smelters and shipping firms in a self-reinforcing circuit of industrial growth. Britain’s advantage lay not in steam or coal alone but in collaboration at scale – a fusion of investment, expertise and enterprise.

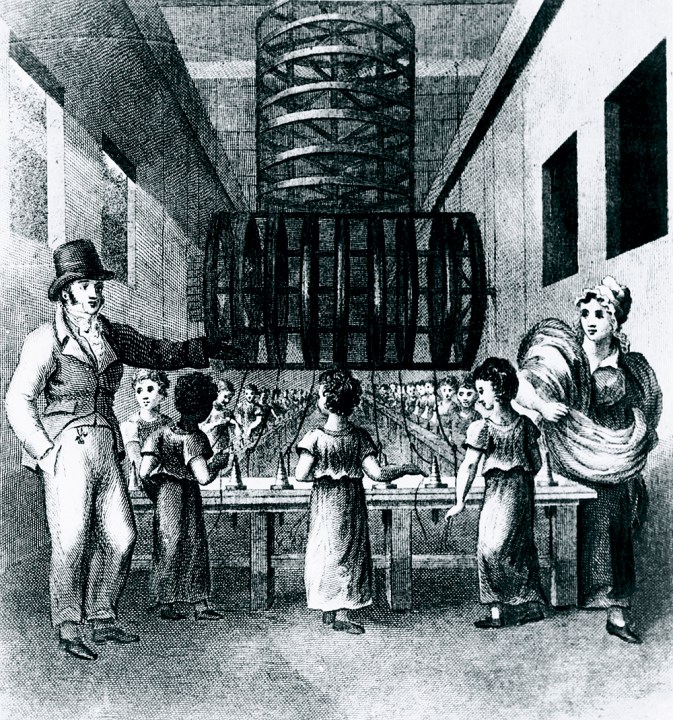

The same web that spread innovation also spread exploitation. Labour was cheap because life was cheaper still, with children working in mills, men in unregulated pits and enslaved Africans in the colonies growing the cotton that fed Manchester’s looms. The Industrial Revolution was both a collective triumph and a collective sin.

The ‘ruthless pursuit of profit’, writes Smith, powered Britain’s ascent while corroding its conscience. Progress and cruelty were spun on the same wheel. Rivers turned black, lungs grey and the nation’s self-image shone ever brighter. The Industrial Revolution ‘transformed not just the landscape but the moral and social fabric of Britain’.

That pattern – invention shadowed by exploitation – is not confined to history. The same circuitry hums beneath the factories of China today. Britain’s first Industrial Revolution and the fourth currently being led by China share the same internal logic: protectionist ambition, disciplined labour, ecological ruin and the serene belief that prosperity absolves everything.

The Industrial Revolution was both a collective triumph and a collective sin

Consider raw materials. Britain’s wealth ran on coal and iron; China’s runs on critical minerals, including rare earths, as well as coal. (Three-fifths of China’s electricity is still generated by what Britain’s industrial heartlands used to call ‘black diamonds’.) In Jiangxi and Gansu, tailings ponds and acid-leach pits testify to an appetite as voracious as anything in Georgian England. Rivers are poisoned, soils stripped and villages are emptied.

Ironically, given China’s dominance of renewable energy technology, much of this pollution is created to feed the world’s green energy transition. In the 18th century, Britain’s pollution was local and visible; China’s spreads across continents, dispersed through supply chains and buried in products stamped ‘sustainable’. In both cases, nature is the expendable partner of progress.

Labour, too, follows the old pattern. Where Arkwright’s mills exploited children and the poor, China’s factories rely on migrants and, in darker corners, on coerced workers. Reports from Xinjiang describe Uighurs, transferred to industrial plants under state supervision, stitching garments and assembling electronics for the global market. The consumer sees the product, not the process.

Even the politics rhyme. Britain’s industrialists lobbied for tariffs to shield them from imports, including iron from Russia. China’s planners do the same for technology and products, protecting domestic firms through subsidies, state investment, export controls and limits on foreign competition.

There is a lesson here for the British government, which still imagines China as a vast economic opportunity. In reality, Beijing is doing what Britain once did: building prosperity by keeping advantage inside its borders and making it difficult for outsiders to operate freely. Like Britain in the first Industrial Revolution, China seeks a lopsided relationship in which others buy its goods but share far less in its gains.

Smith’s great strength is to show that industrialisation is less a moment than a method. Instead, it is a self-replicating pattern of ingenuity and amnesia. His prose is cool, precise and quietly damning. He writes of networks, but his real subject is complicity: how societies grow rich by outsourcing their conscience. The Industrial Revolution, he implies, never ended; it simply migrated east, trading steam for silicon and Manchester soot for Shanghai smog.

By the close, it feels as though Arkwright’s waterwheel is still turning, only now it powers an entire planet. China’s rare earth refineries are its new mills, its supply chains the new empire. The old faith endures – that growth excuses its ghosts. The British Empire may have vanished, but a similar network remains, whirring beneath our comforts. It is invisible, tireless and, despite all our progress, still profoundly unclean.

Comments