Let’s talk about Tucker. The Beeb’s mockumentary The Thick of It has been hailed as a brilliantly incisive glimpse into the corridors of power, and its diabolical protagonist, the scheming spin-merchant Malcolm Tucker, is regarded as a hilarious portrait of a modern political propagandist. That’s one view, anyway. Maybe I’ve got a blind spot. Maybe my sense of humour’s gone missing. Maybe I romanticise the ideals of public service because my mum and dad worked in Whitehall, but I’ve never understood the praise heaped on this cruel and distorted fantasy.

It’s possible to overlook the relentless swearing, the vapid characterisation and the ever-predictable storylines. It’s even possible, although it’s much harder, to ignore the scriptwriters’ self-imposed ‘squashed testicle’ quota, which stipulates that a new variety of scrotal mutilation must be mentioned every two minutes. But what’s impossible to accept is that Malcolm Tucker could work as a ministerial adviser. An obsessive violent thug like him would be unemployable by a firm of bailiffs, never mind by the government. And the show’s authors don’t seem able to explain — although I’ve never watched long enough to check so I may be wrong — why Tucker’s sadistic criminality isn’t exposed by an undercover hack with a hidden camera.

The show’s esteemed predecessor, Yes, Minister, was not entirely without flaws but they were easier to forgive. Often wordy, occasionally too static, at times stuffy and a little smitten with itself, the show had one absolute virtue. It was authentic. Ministers and their advisers do not charge about like hobbits on crack shouting naughty swear-words. They relax in elegant surroundings sipping malt whisky and striving discreetly to advance their personal interests while pretending to act for the common good. That’s how it works.

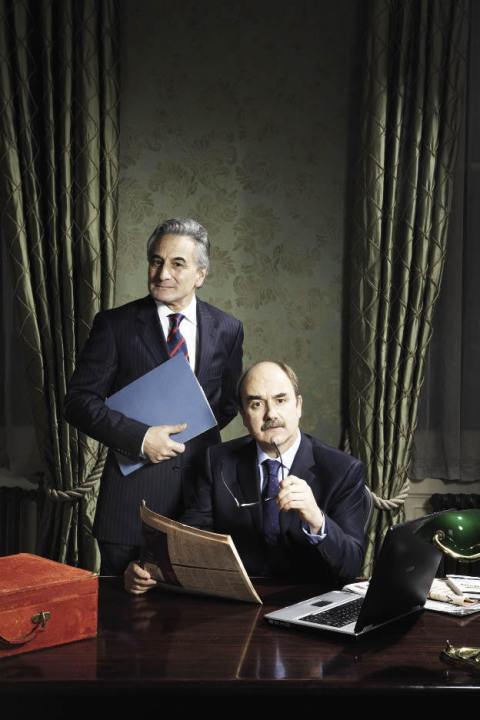

The authors of Yes, Minister have written a completely new play, which imagines how the coalition might look after several years of wear and tear in government. The setting is Chequers where the Prime Minister is desperate to rescue his premiership by signing a treaty with an oil-rich Asian dictatorship. The snag is that the Asian foreign minister demands the services of a call-girl in return for signing the agreement. No tart, no treaty.

Luckily, one of the Chequers staff, and his attractive young daughter, are working in Britain illegally and when the PM discovers their refugee status he comes up with a solution. Pimp the daughter, fast-track her visa and secure the gratitude of the priapic Asian. The writers deserve full credit for selecting this faintly seamy storyline. It removes the characters from the clubbable milieu of Westminster and forces them to tackle the issues of the globalised world.

The show is thoroughly in tune with the times. The Prime Minister employs a special adviser whose brief is to neutralise and outwit the Civil Service. (She’s called Claire, she wears a trousersuit and she doesn’t scream insults at everyone.) Sir Humphrey has succumbed to a very modern temptation and is suspected of using his position to speculate in the currency markets.

Henry Goodman brings out all his character’s wily and self-satisfied vanity and David Haig gives a hugely energetic account of a prime minister at the end of his rope. No one does frenetic befuddlement like Haig. Tim Wallers, in a cameo, gives the best parody of Paxman you’ll ever see. The jokes surge forth on ever-trundling wheels of mirth and suddenly they come skidding to a halt in Act Two when the dialogue turns to climate change. The cult of global warming is treated to a detailed and scathing analysis. Presumably, this joke-free interlude earns its place because it represents the authors’ conservative views. What a turn-up! Right-wing satirists in the theatre are as rare as good-looking delegates at the TUC conference.

Richard Bean’s new play The Big Fellah is set in New York and follows a group of IRA sympathisers during the Troubles. Bean’s speciality is social comment delivered with bundles of levity, and terrorism suits his talents rather poorly. He’s certainly done his research. The characters are a gruesome squad of psychos, sentimentalists, grudge-mongers and grievance-freaks. Life in the IRA is fraught with danger — primarily from one’s own side. In a makeshift army of criminals, the command structure is constantly changing and the duties of counter-espionage and military policing are performed not just by the same units but also by the same individuals. One soldier can accuse another of treachery and have him shot within an hour.

Bean faithfully traces the story through three decades of conflict right up to the moment when the planes fly into the Twin Towers and America’s romance with terrorism expires. So does the drama. Not a rewarding conclusion. Let’s hope Bean isn’t planning to swap the job of entertainer for the role of distinguished playwright. What a demotion that would be.

Comments