Arabella Byrne has narrated this article for you to listen to.

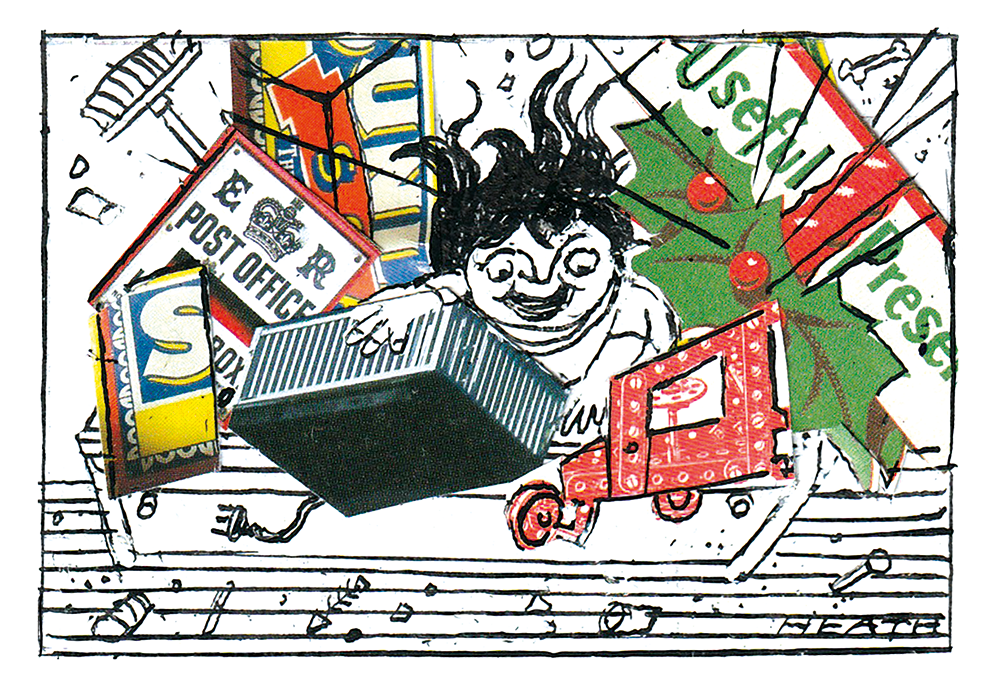

Call me disgusting, but I like rubbish, and I like it best from a skip. I am also in good company. In his 1967 poem, ‘The Bin Men Go on Strike’, Raymond Queneau riffs on the fantasy of bins stuffed with works of art, the ‘Mona Lisa’ lying askew by the spent toothpaste tube, or a Géricault smeared with pigeon shit, jettisoned by an ignorant philistine.

This is an elaborate joke, bien sûr, designed to make us reconsider aesthetics in general, but its point holds: can we conjure art from the soiled and fragmented? Can we overturn economic values – and even meaning – as the ragpickers or, as Baudelaire had it, the chiffoniers of our time?

I like to think so. Skip-diving, or the practice of helping oneself to objects from a skip, is on the rise. According to SkipHire UK, Brits are increasingly prone to diving into these treasure troves, placed on common or private land across province and city.

Notionally, skip-diving is understood as environmental altruism dictated by economic imperatives or, as TikTok star DumpsterDiver says, ‘free shit’. The website Junk Bunk interprets modern skip-diving as driven by the cost-of-living crisis and the increasing commitment to dealing with waste in a sustainable manner. Thankfully, though, I also read that it is ‘not necessarily ideological’. Unlike its twin movement ‘freeganism’, whereby scavengers fish discarded food out of bins, driven by anti-capitalist instincts, skip-diving is pure pragmatism.

This makes sense. Why allow a working Smeg toaster you can’t afford go to landfill when you could take it home with you? Simply put your dark glasses on, look both ways and then shove it quietly into your bag. I say quietly because skip-diving, while not illegal, is not exactly legal either. So much the better, for the thrill-seeking divers among us.

The 1968 Theft Act in England and Wales and the common-law Theft Act in Scotland state that items may be taken if the owner considers them to be abandoned, although you could be done for trespassing if the skip is, as is often the case, in someone’s drive.

To avoid prosecution, or unpleasant pavement arguments with strangers, skip-dive in London. Loiter around Belgravia or South Kensington long enough and you will find an Oka lampshade or, as I did, a Victorian cachepot in a skip off the Brompton Road.

Call it zeitgeisty if you like, but I come from a long line of skip-divers. My mother talks proudly of the Regency wall brackets she found in a skip in Chelsea. My godfather, walking past a skip in Hammersmith in 1989, found an unframed George Morland print which he rescued before it started to rain. Another friend describes walking past a skip in Kensington only to see a canvas sawn in two and signed by Augustus John. Here was art, left in the rudest possible sense and without its conventional framing. Truly, an ode to carelessness.

Not for the cautious middle classes who surely see this as a deeply vulgar pastime, skip-diving is an example of the conjoining of snob and mob. Show me a skip and I will wager that both builder and baronet have stuck their hands in to unearth anything from a Victorian fireplace to a Freeview TV.

Join Spectator writers on Thursday 30 October for drinks to celebrate the publication of Best of Notes on.... To book tickets, go to club.spectator.co.uk/events

Comments