This year, the sequence of galleries has been subtly altered, and for a change we enter the fabled Summer Exhibition (sponsored by Insight Investment) through the Octagon rather than Gallery 1. This brings the visitor straight into the heart of the show, and it’s quite a good idea at this point to turn right into the Lecture Room for a gallery dedicated entirely to RA members, hung by that éminence grise, Michael Craig-Martin. Of course this is Craig-Martin’s choice, so the more traditional practitioners are excluded, but the Lecture Room nevertheless looks better than it has done for years.

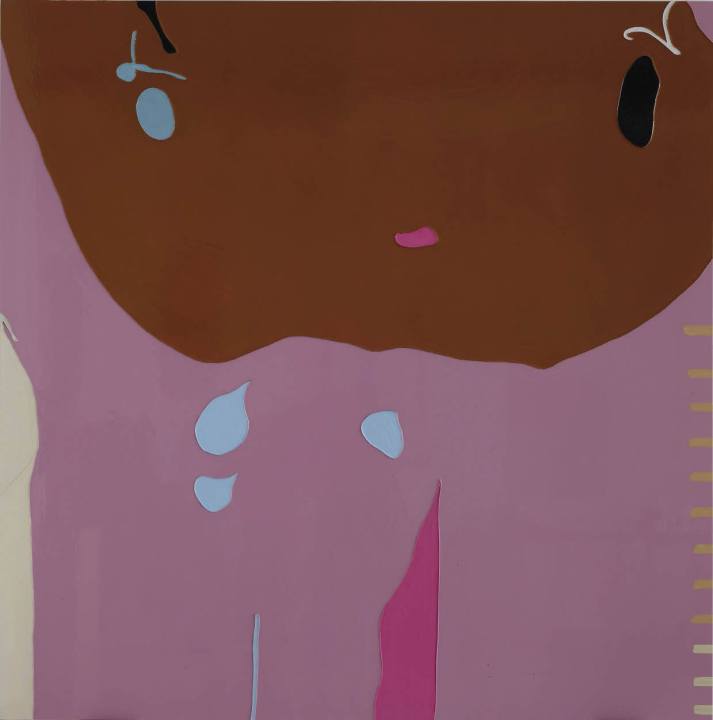

A big tattooed head by Tony Bevan keeps company with Humphrey Ocean’s ‘Windscreen’, a roughly massed urban landscape. An open-structure wavy wooden sculpture by Richard Deacon stands on its side, an unexpectedly modest Anish Kapoor nearby. There’s a rather evocative and romantic oil called ‘Belvedere’ by Christopher LeBrun, chief hanger of the exhibition, a column of Tacita Dean photographs and a shamanic china clay hand print by Richard Long. A wriggly laminar bronze by Tony Cragg hovers like a dust-devil. A classic Joe Tilson Venetian relief hangs next to one of Allen Jones’s cool but perky androids emerging in pink from a crumple of electric blue. Gary Hume’s painting nearby is remarkably luscious in a restrained and elegant way, contrasting nicely with the imprisoned fervour of Michael Sandle’s blocked-in submarine.

Richard Wilson makes typically witty reference to The Italian Job with a coach see-sawing over the top of the De La Warr Pavilion. Cornelia Parker contributes a clump of suspended flattened silver plate — an old idea for her, but not ineffective. Craig-Martin himself is represented by a candy-coloured pink garden gate on a turquoise ground, over-stencilled with the word ‘Fate’. He may be leading us up the garden path, but it’s an enjoyable journey: this room on its own is a substantial exhibition.

But stamina is what’s required for the Summer Exhibition, and there are still well over 1,000 exhibits to admire or ignore. Cross back through the Octagon and relish the mixed delights of Gallery III. A large canvas by Gillian Ayres proposes a bold design of friendly plant spears and vases like modernist altars, while Barbara Rae’s vivid red ‘Killala’ jousts with Maurice Cockrill’s Hoyland-ish ‘Bird Calls’. (John Hoyland is this year conspicuous by his absence from the show.) In such company, Ashley Hanson’s ‘Cape Cod and the Islands’ somehow manages to hold its own in orange and blue-green. An expanse of Adrian Bergs pays tribute in small panels to Sheffield Park, and in a large triptych to low tide at Beachy Head, the beach rather than the more famous cliff. On the end wall there’s a delightfully painterly Per Kirkeby, vaguely cataclysmic but essentially benign, dramatic against the chocolate-grey walls. Also good here is Chris Appleby’s unabashedly figurative ‘Dr Dee on Bruno’s Donkey’, Eileen Cooper’s youthful longings, Gus Cummins’s jack-in-the-box still-life and Mick Moon’s exquisite ‘Towpath’ tracery.

I also enjoyed Arturo Di Stefano’s monochrome of Cézanne as an ancient Charlie Chaplin juggling with a chair, cane laid aside, the mysterious and minimal abstract by Alex Calinescu, and an excellent run of magical Mick Rooney paintings, whose work never ceases to beguile and enthral. Above are some expertly dabbed flower and garden paintings by Tony Eyton, and a large view of Australia’s Uluru. Galleries II and I have been quite densely hung this year with smaller pieces. In II, there are notable things by Paula Rego, Andrzej Jackowski, Norman Ackroyd, Peter Freeth and Bert Irvin. In Gallery I, three flat cabinets of artists’ books extend the definitions of printed work, supported by fine etchings and monoprints on the walls by the likes of Leonard McComb and Keith Coventry. Gillian Ayres shows two starburst woodcuts, a new medium for her, hung above a couple of her more familiar carborundum prints with hand-colouring. Here also is a Glen Baxter digital print, subversive in the archbishop’s library, ‘updating his archive of pornography and railway memorabilia’.

The Weston Rooms look very different this year. Usually, the larger one is packed floor-to-ceiling with prints; this year, it is distinguished by a refreshingly spare hang, with such paintings as James Hugonin’s lucidly controlled traffic-jam of colours and Stephen Chambers’s feast of cups given room to breathe. There’s a very odd and intriguing Derek Boshier acrylic called ‘Patterns of Fashion’, a cream embossed gas station print by Ed Ruscha, and an unusual pastel by Tom Phillips, always capable of surprising us, entitled ‘Siegfried’s Funeral March’. Also of note are a couple of scruffily evocative interiors by Vicken Parsons, and a cabinet of pots by the ubiquitous Edmund De Waal. In the Small Weston Room the usual hugger-mugger is reduced, but there are good things by the nonagenarian team of Bernard Dunstan (particularly ‘Morning Drawing’) and Diana Armfield (especially ‘Dog on the Beach’), a sensitive depiction of winter-bitten water lily leaves by Michael Whittlesea, and an armorial banana by Robert Dukes. I liked the manic notation of Alexandra Blum’s drawing of Kingsland High Street, and the deft, economical still-life of Ffiona Lewis.

Back through the galleries to the north side of the building and Gallery IV, where work by some of the Academy’s finest sculptors may be found: Nigel Hall, David Nash, Ken Draper (good to see a 3D piece by him, besides his usual pigmented reliefs), John Carter, Ann Christopher and an intriguing group of drawings by Alison Wilding. John Wragg’s paintings are expectedly compelling, with ‘Falling Flowers’ the most memorable. Gallery V is another lucidly arranged room, hung by Tess Jaray (note her own gridded colour panels), with a range of modes from the quiet threaded vertical pulse of Belinda Cadbury’s drawing to the block of Basil Beattie lunettes, via such individualists as Melanie Comber, Tim Hyman, Luke Elwes and the mysterious atmospherics of Philippa Stjernsward.

The architecture room I leave for other experts, merely noting the preponderance of perforated forms and Piers Gough’s green glazed ceramic model for a Maggie’s Centre in Nottingham. Gallery VII contains a lovely group of four small cut bronze sculptures by Bryan Kneale, rather a good David Tindle of a phone off the hook on a single bed, and Eileen Hogan’s study of Ian Hamilton Finlay surrounded by a lot of words. A much-needed shaft of wit can be found in ‘Max Ernst’s Trampette’, carefully spiked by Midge Naylor. Gallery VIII, another sculpture room, is rather crowded, though a couple of Ivor Abrahams’s kiosk-beasts and a shelf of Geoffrey Clarke’s aluminium portals stand out, along with Frank Bowling’s large colour-filled abstract, Robin Greenwood’s sprawling steel ‘Capital and Labour’, and two powerful charcoal drawings by William Tucker.

In Gallery IX, a group of small paintings pays tribute to Leonard Rosoman’s poetic talent, while a splendidly crusty painting by Jeffrey Dennis is juxtaposed with Jeffery Camp at his most abstract: a dark vision of energies and explosions. Nearby, a large panorama of Dagenham by Jock McFadyen is beautifully painted. Gallery X ends the exhibition in a cacophonous hang like the worst old days of the summer show, pictures cancelling each other out, despite such potentially enjoyable things as flower paintings by George Rowlett and Sarah Armstrong-Jones . This is the weakest room in the 243rd Summer Exhibition, which generally stands up remarkably well to the conflicting demands that continue to beset it.

Comments