Tanya Gold has narrated this article for you to listen to.

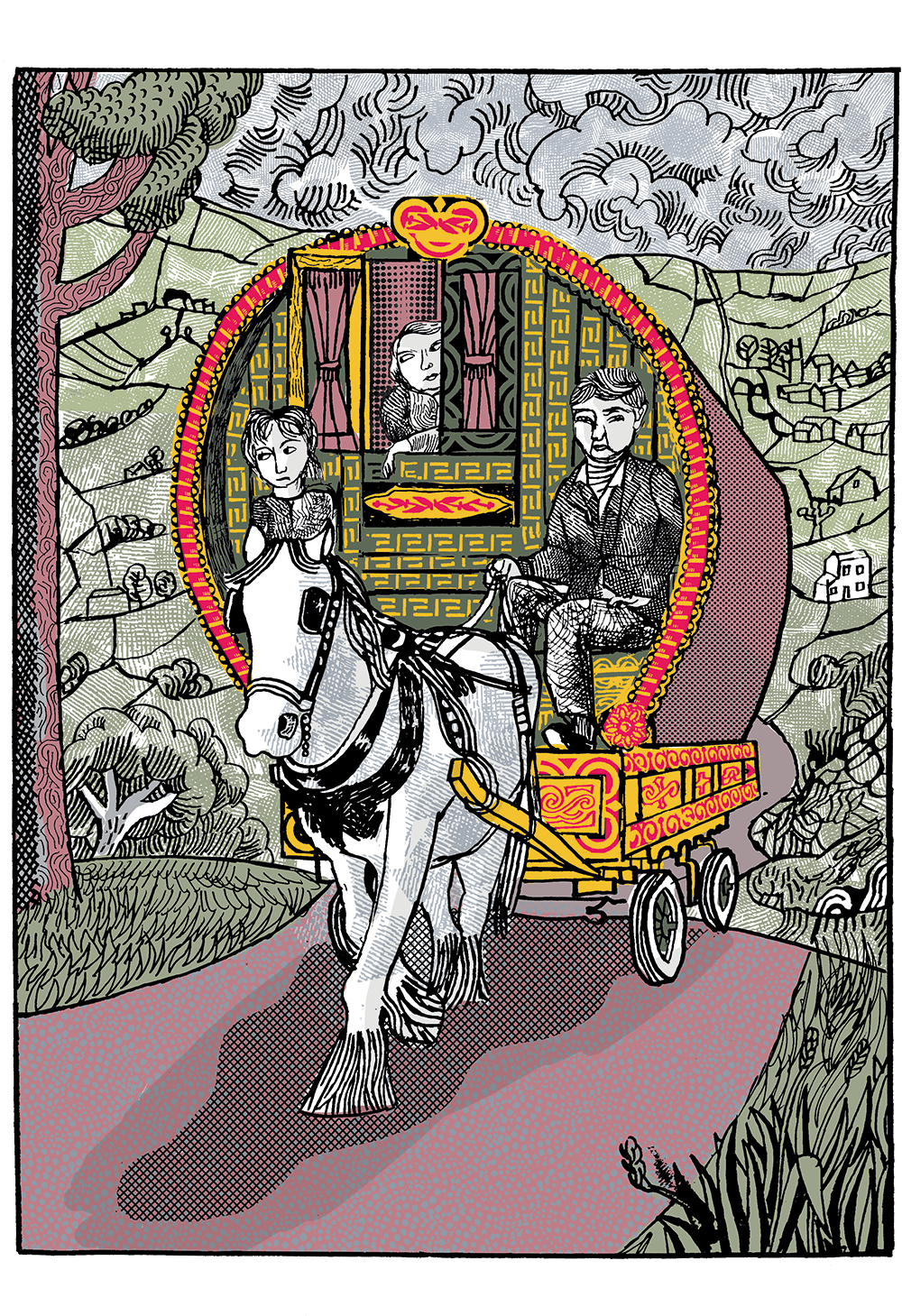

‘Don’t use our real names,’ says the teenage gypsy. ‘Other gypsies will laugh at us.’ Even in a tracksuit, the girl is crazy beautiful, and strangely remote. She is talking to me because her mother, whom I call Susan, has been ordered to remove her caravans from a council site in the West Country. If Susan, mother of five, and carer to two grandchildren, is evicted by Cornwall council, her family will be scattered to the winds. It’s a peculiarly awful fate for gypsies. They are tribal, and family is everything to them. It is the first eviction of a gypsy from a council site in this county.

The site is silent and dour: rows of caravans, ugly piles of rubbish, though Susan’s part is neater than most. Much of the rubbish is fly-tipped by outsiders, surely a metaphor for the treatment of gypsies in history. There were gypsy hunts in Saxony; forced sterilisation in Sweden; kidnap of gypsy children in Switzerland, even in the 1970s. Like Jews, with whom gypsies share more than is acknowledged, they have a monument at Auschwitz to what they call ‘the Porajmos’ [the devouring]. I have seen with my own eyes at Yad Vashem a Nazi document mandating sterilisation for all gypsies ‘for reasons of national hygiene’.

Modern Britain does not understand or like gypsies. The name ‘gypsy’ itself is a misunderstanding, a corruption of ‘Egyptian’ though they were nomads from India. Multiple governments have restricted their freedoms. In May, the High Court found that the parts of the 2022 Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act were, in regard to gypsies, ‘incompatible’ with the ECHR: under the act, police can imprison people in unauthorised camps and seize their property.

Last month, it was alleged that gypsy children were forcibly prevented from attending a Christmas market in Manchester by the police. They were, according to The Traveller Movement, ‘humiliated, manhandled and denied basic respect and safeguarding by the very authorities tasked with protecting them’.

A gypsy boy rides up on a bicycle, and says he will look for Susan. He looks intensely curious to see someone from outside the site; so curious that, when we drive to the lower site later, he jumps in the car with us, then decides he is bored and jumps out again. When we find Susan, she sits in her caravan, her face creased with agony, as distraught a woman as I have ever met. She is pale and blonde and heavy, and she can barely speak. There is a similarity, and a difference, to female pain. It is obvious that Susan’s life is falling apart: if it weren’t, she would never have agreed to meet me.

Susan’s children display the kind of modesty rarely found outside Black Beauty but they are not afraid of me

English is her second language, and she cannot read. I have seen a pile of documents about her that she cannot read, and this feels strangely intrusive. Susan receives benefits and is vastly in arrears, which she is paying back, though slowly. A series of antisocial behaviour allegations against Susan and her family were presented to the court. It was a strange document, a litany of offence, and more curious for that.

For some allegations, Susan offers explanations. Her sister came to the site without permission. It was, Susan said, the day of their mother’s funeral. Could she turn her away? They set a fire. Susan said they burnt her mother’s possessions, a gypsy custom. The Daily Mail knows this – it printed a story about the four caravans of ‘the Queen of the gypsies’ set alight in ‘an ancient rite’. Why doesn’t the council know it? Susan left emergency accommodation booked for her by the council in cold weather. Her daughter was sectioned with her child elsewhere, she said, and she had to care for them. To me, Susan’s children display the kind of modesty rarely found outside Black Beauty, but they are not afraid of me. Usually, they run from authority. A gypsy child threatened to spit on the fire crew and said that she had Covid. A gypsy child made a racial slur in the presence of a bin man, who now requires a chaperone. A gypsy child locked herself in the utility block and refused to talk to the police. A gypsy child ‘exited the defendant’s caravan with a knife. The defendant’s daughter proceeded to walk past fire officers with the knife and then sat on a grass area with it still in her hands’.

Susan had no legal representation so the written defence was scant: a letter from a GP, listing her medication for depression; a longer letter about one of her daughters, who cuts herself and sprays perfume in her throat; a letter from the headmistress of a local school, saying one of the grandchildren ‘is settled in our school environment and attends school regularly’, a sentence I found strangely heartbreaking.

The year the arrears began Susan lost a child, a grandchild, a brother and her parents. ‘I tried to cope with all these deaths, and try to look after all my family,’ she says. ‘I am under mental health [help] for depression, I’m trying to get all the debts sorted and the kids are older and more behaved. I do think they were acting out a lot through grief and depression.’

She doesn’t know what she will do if she is forced to leave. ‘I have trailers to live in and I won’t have anywhere to put them, and I am a woman by myself trying to do my best. My kids have been through hell and we’re just starting to get back to normal.’

It may be too late for Susan, though not for others. She was informed that she is to be evicted and that the children will be taken into care, which is good news for private equity, but rather less so for the taxpayer, Susan and her family.

My instinct is the council and this family do not understand what the other needs from them, and that this family is safest where they are. Just before Christmas, Susan was given leave to appeal, and the eviction was delayed. A finger of hope stretches into the next few weeks and no further.

Comments