Could Boris do a Harold Wilson? Over the years there has been much speculation about the sudden resignation of Wilson as prime minister less than a year after he had settled, apparently for good, the momentous question of Britain’s future in Europe via the 1975 referendum. Was he forced out by MI5? Had he already got wind of his early-onset Alzheimer’s? Was there some other hidden personal scandal that would have emerged had he not stood down?

The truth was rather more bland: it seems more likely that Wilson had just lost his appetite for the grind of the job. In a resignation minute circulated to all cabinet ministers he observed: ‘It is a full-time calling. These are not the easy, spacious, socially-orientated days of some of my predecessors… I have had to work seven days a week, at least 12 to 14 hours a day.’

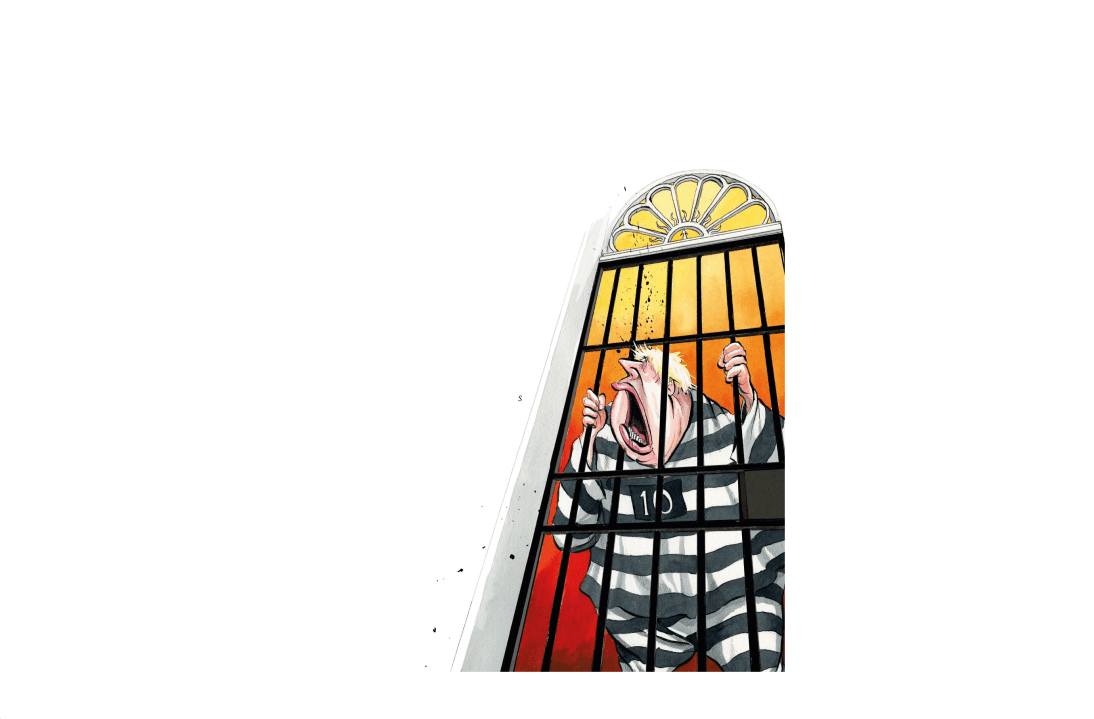

Few would suggest that Boris Johnson, for all his gifts, ever had a Wilsonian concentration span or a Stakhanovite work ethic. So it requires no great leap of imagination to suppose that the not easy, not spacious, not socially-orientated days he is enduring right now are not what he had in mind for his premiership.

Throw in divorce, fatherhood again at 56, an impending further marriage and a touch-and-go spell in intensive care that may have left its mark on his own capacity and it’s easy to see why the gossip has been building that Johnson may do a Wilson early in 2021, once the main loose ends of Brexit have been tied up.

‘He is hating it. He can’t make his mind up on stuff. His rupture with his family occupies his thoughts a lot’

As someone who knows him well told me this week: ‘He is hating it. He can’t make his mind up on stuff. His rupture with his family occupies his thoughts a lot. Dominic Cummings has mainly gone over to work with Michael Gove on Brexit and he knows that a lot of the other people around him are second-raters.’

While his success in electoral politics cannot be declared over — as the continuing Tory poll lead attests — his failure in governmental politics, following a tenure as Foreign Secretary that was decidedly ropey, is close to becoming an acknowledged fact of life in Westminster.

A natural flippancy, an overwhelming desire to be liked and a tendency to think he can get away with not doing his homework are the three traits most often cited as his undoing.

This week all three were on display, as when he was blind-sided in front of the Commons liaison committee over Northern Ireland Secretary Brandon Lewis’s assessment that the EU was, in fact, negotiating in good faith compared to his own assessment that it wasn’t.

Making it up as he went along, Johnson theatrically declared that it was always possible his own assessment would be proved wrong by virtue of the EU behaving more reasonably, smirking and looking around the room for signs of approval, amusement or admiration as he did so.

And then there was that interview in the Sun where he said that people should not dob in neighbours for breaking the rule of six — adjudged by his own administration as essential to public health — unless they were having a rumbustious, US frat-house style, full-on party — ‘hot tubs and so forth’. That completely cut the ground from under ministers and MPs who had through gritted teeth told interviewers that yes, of course, the right thing to do was to let the authorities know when this law was being broken.

With an extremely tough autumn on the Covid front now the central expectation of ministers and officials, this style of leadership really does seem singularly ill-suited to the times.

No wonder then that the name of Michael Gove is once more on the lips of the Tory tribe, with the influential columnist Paul Goodman floating the idea of him being made Deputy PM in January, once the Brexit saga is concluded.

One is struck by the degree of admiration for Gove’s brainpower, strategic nous and sheer skill at government that is felt across the political spectrum. Nigel Farage is but one unlikely admirer. At times each of the three most recent Tory PMs have viewed Gove as untrustworthy, but equally all three have also at times found him indispensable.

That is how he is seen right now and it may be that bolstering someone good at being electable but bad at governing with someone good at governing but bad at being electable will bring a belated sense of coherence and grip to the Johnson premiership.

Equally, even that may simply lead to more Tory MPs wondering whether it mightn’t be an idea to install someone who is good at both. It would not be the very greatest shock — certainly not a shock on the scale of Wilson’s resignation — were Johnson himself to reach that view.

As he said once before when defining the mission facing the UK Prime Minister: ‘Having consulted colleagues… I have concluded that person cannot be me.’

Comments