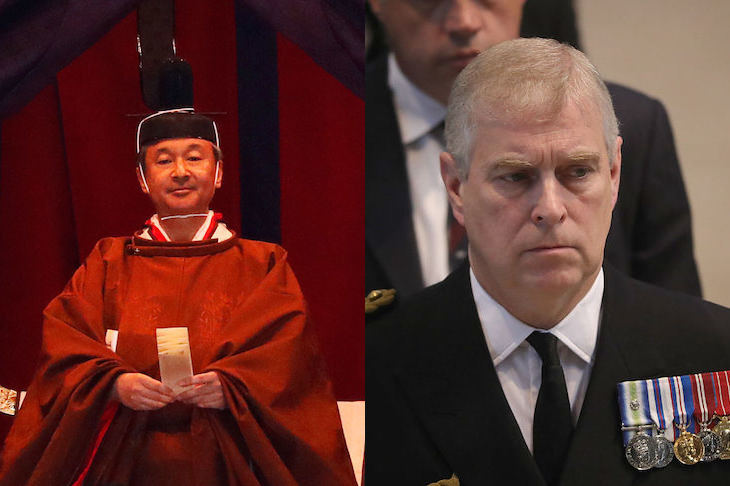

Most British people who watched Prince Andrew’s cringeworthy interview with Emily Maitlis this month will have done so with a certain amount of disbelief. But for Japanese observers, the spectacle of a crown prince being asked awkward questions about his private life by a forensic interviewer would have been totally incomprehensible.

The Japanese royal family doesn’t really do big royal scandals. It’s not because embarrassments never occur, or that individual members aren’t prone to all the usual human failings, it’s just that the institution as a whole is much better protected, the media far more carefully regulated, and the public has significantly less appetite for juicy tidbits of royal gossip.

The Japanese royals are ‘managed’, which effectively means controlled by the notoriously all-powerful IHA (Imperial Household Agency) – a small army of civil servants who operate independently of government. They draw up the royal family’s schedules, write their scripts, advise them on everything from choice of clothes to choice of life partners, and generally keep a beady-eyed watch on the royal family’s every waking move.

The IHA extends almost as much control over the media. Access to the Japanese royal family for the respectable mainstream newspapers (the tabloids and gossip rags can print what they like – and sometimes do) runs directly through the agency, who serve up a bread and water diet of mundane press releases, and heavily choreographed photo opportunities. The resulting ‘official’ press coverage is predictably deferential. And dull.

Japanese royal scandals in the last few decades seem puny when compared to the box set mini-series that is the Windsors. The biggest of these in recent years has been the will-they-won’t-they saga of Princess Mako (the closest thing the Japanese royals have to a star) and her supposedly unsuitable fiancé, Kei Komuro, a law firm employee the young princess fell for at university.

All the scandal amounted to was skeletons rattling around the groom’s family closet, though they weren’t so much skeletons as a few musty old bones. There was financial irregularity, a family suicide, and – worst of all perhaps – rumours of possible Korean ancestry. This meant official approval for the match was, at first, only reluctantly given. Then, when a few more bones were unearthed, the marriage was postponed, and the young swain conveniently dispatched to New York to ‘continue his studies’.

And that’s it. All in all, it was more like the subplot of an Anthony Trollope novel than anything that would pique the appetite of the ravenous British tabloids.

Which is not to say seedier rumours haven’t swirled around the Chrysanthemum throne. The closest the Japanese have come to anything approaching a sex scandal was a claim a few years back that Prince Akishino, the new Emperor’s brother, and father of the probable next Emperor, had a mistress in Thailand. Prince Akishino has always denied the allegations.

Described to me by a Japanese friend as a ‘wilder version of Prince Harry’ young Akishino made several visits to the ‘Land of Smiles’ and stories of a liaison were printed in a gossip mag, though no photographic evidence ever emerged. The allegations became common knowledge, but the respectable press took no notice, there was no public outcry, and absolutely no question of the Prince being expected to answer questions on the matter on national TV. The story quickly withered away.

This lack of interest is partly a consequence of Japan’s attitude to its royal family, and a consequence of how they are presented. The royals, via their IHA handlers, make a virtue of being boring, almost liminal characters, scarcely allowed personalities of their own, just figures waving from balconies or from the windows of limousines. Having never been built up in the public imagination, there is not much fun to be had in tearing them down.

The Japanese royals are hardly regarded as distinct individuals at all, but rather as parts of a greater whole, a collective living embodiment of Japan for which there is broad, if not wildly enthusiastic, approval among the citizenry. The British royal family had a similarly protected existence once, and the British press were much more circumspect in their coverage. But somewhere down the line the two royal families chose different paths: the British sought approval and survival by opening up their lives, courting celebrity and, to a certain extent, inviting media attention, while the Japanese deliberately chose to be as anonymous and uncontroversial as possible.

It’s not entirely clear which royal house is in the healthier state.

Comments