‘The 43-force structure is no longer fit for purpose. In the interests of the efficiency and effectiveness of policing it should change.’

That was the conclusion of a review of the police service of England and Wales in September 2005 conducted by the independent policing watchdog, then known as HMIC. The findings led Tony Blair’s government to attempt a massive reorganisation of policing which at one stage would have involved merging police forces to create 12 larger ones.

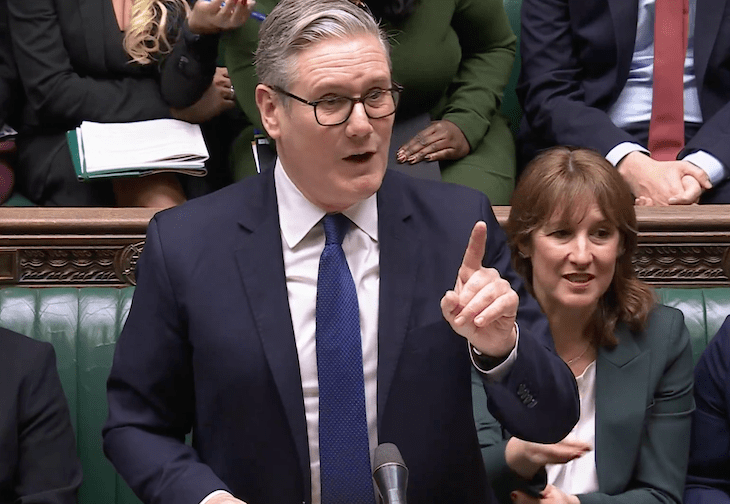

However, the merger plans became mired in controversy before being abandoned and the ‘change’ recommended by HMIC never happened. Twenty years on, the lessons from that botched reform process must be learned quickly by Sir Keir Starmer’s administration, and its new Home Secretary Shabana Mahmood. She, it appears, is weighing up the pros and cons of a policing shake-up on the same kind of scale.

A policing white paper, which should have been published weeks ago, has been delayed until the New Year, while Mahmood considers whether it is radical enough. The initial version, which was drawn up under Yvette Cooper’s 14-month tenure as Home Secretary, contained plans to centralise policing functions, such as air support, forensics and IT, and streamline police procurement to generate savings. Drafts of the document are believed to have nodded towards the need for a more coherent structure, but without including a commitment to make substantive alterations to the 43-force model.

Mahmood, however, has told police leaders that she had a track record of reform at the Ministry of Justice and would be a reforming Home Secretary, too, when it comes to policing. ‘The structure of our police forces is, if we are honest, irrational’, she said at a conference in November. ‘We have 43 forces tackling criminal gangs who cross borders, and the disparities in performance in forces across the country have grown far too wide, giving truth to the old saw that policing in this country is a postcode lottery.’

A number of police chiefs, among them the Metropolitan Police Commissioner, Sir Mark Rowley, are urging the Home Secretary to slash the number of constabularies to 12 or 15. Rowley has said ‘bigger and fully capable’ forces would be able to make better use of modern technology and the ‘limited funding available’ and reduce duplication and waste by combining back office services such as vetting and human resources.

Many of the same arguments were made by Charles Clarke when he tried to steer through police mergers as Blair’s Home Secretary between 2004 and 2006. It was said then that the plans could save policing up to £2.3 billion over ten years but one of the key stumbling blocks proved to be the up-front costs required to facilitate such a large-scale reconfiguration. The now-defunct Association of Police Authorities (APA), which at the time represented local bodies overseeing the 43 forces, estimated it would need initial investment of £600 million. The APA said no police authority would agree to the plans unless the government pledged to meet the costs (which it would not do).

Clarke’s approach, 20 years ago, was widely viewed as a rushed attempt to impose mergers on forces. After the HMIC report was published, he gave chief constables and police authorities just three months to come up with a business case to support their preferred option for amalgamations, a tactical error which served only to strengthen opposition to the idea, with the Conservatives attacking it as a ‘costly, disruptive, dangerous, one-size-fits-all’ scheme that jeopardised local policing. In towns and villages served by small police forces there were genuine fears that their communities would be neglected if their constabulary was subsumed into a far bigger one.

By the summer of 2006, Clarke had been sacked following an immigration scandal, and the Home Office had watered down the merger plans after realising that they would work only if the forces involved consented. Just two had: Lancashire and Cumbria. The problem, however, was that council taxpayers in the two counties paid different amounts towards policing. A merged force would involve harmonising council tax rates but no agreement could be reached on how that would be funded. Nine months after that landmark HMIC report police mergers were dead.

Things are a little different now. Police and crime commissioners, who replaced police authorities and might have led opposition to mergers, have been neutered after Mahmood announced their abolition in 2028. Chief constables are more united in their support of the idea than they were in 2005, principally because it could help them make savings with budgets so tight. And there is arguably greater appetite from the public for reform, with confidence and trust in policing having dipped in recent years.

But if Mahmood is to press ahead with mergers, she must not adopt the top-down strategy of her lofty predecessor Clarke. That will be doomed to fail. If reorganisation is to work, it must start with local discussions in areas where it makes sense from an economic and governance point of view – and where people buy into the idea.

For example, combining the constabularies of Norfolk and Suffolk in 2028, when a new mayor for the two counties is elected, might be a good starting point. As would a regional force of Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire, where a mayor for the East Midlands has been in post since 2024. But the Home Secretary must make the argument, setting out the benefits, as well as being realistic about potential downsides.

The 43-force structure is no longer fit for purpose, just as it was no longer fit for purpose two decades ago. But the mistakes from that bungled policing overhaul under Clarke’s watch cannot be repeated.

Comments