Without Boris Johnson there would be no Conservative majority. The millions who turned to him at the last election were not voting for the Tories, but for something (and someone) very different: they wanted Brexit and they trusted him to deliver it. Without Johnson, the Tories would struggle to keep his electoral coalition together, so when the Prime Minister asks his MPs to vote for something they dislike, though they denounce his madness, they do it.

But now, for the first time, these MPs are beginning to waver. They’ve seen a pattern in the PM’s behaviour, they’re beginning to understand how each debacle will end, and they’re becoming wary. This is how it goes: a bad idea emanates from 10 Downing Street, to exonerate Owen Paterson, for example, or to let companies dump sewage into rivers. No one in No. 10 thinks through the implications, and the PM has no appetite for criticism, so the idea is announced. Uproar ensues and so, inevitably, there’s a U-turn. The latest bungling was of such a scale as to turn an isolated incident into a full-on sleaze scandal, with Tory MPs (who warned of this) looking on aghast. They feel exposed, let down, and have begun to ask what’s going on.

The answer is complicated and exposes the biggest weakness in the Johnson operation. He has allowed it to become more of a court than a government, and one that magnifies rather than mitigates his weaknesses. Instead of having around him senior advisers who can warn him of impending disasters, Johnson now has courtiers who offer affirmation and reassurance. Even when a bad idea is exposed, the courtiers console the PM that it’s no fault of his, and so No. 10 is in denial about its own errors and the damage it is inflicting on the reputation of the party — and of the Prime Minister himself.

The Paterson debacle perfectly illustrates how this court of chaos operates. At various points in this saga, Johnson should have been told in no uncertain terms that it was madness to overrule an all-party sleaze watchdog without cross-party agreement. Disaster was guaranteed. Instead, when it became clear that he was in a gung-ho mood, any murmured objections melted away.

The lack of critical thinking and rigorous questioning is widespread. Johnson’s madcap attempt to skip self-isolation at the height of the pingdemic, for example, should have been quashed as soon as it was suggested. Instead, it took public outrage to make this basic point. If he were willing to face down media outrage, if he could summon the spirit of Thatcher, it wouldn’t matter as much. But for all the superficial bombast, when his ideas hit serious opposition — over housebuilding, or giving free school meals in school holidays — he buckles. Almost every time.

Slip by needless slip, a party elected on a promise to cut taxes has somehow mutated into the very thing it warned voters against: one that is pushing taxes up to a post-war high. If this provided a once-and-for-all fix to care homes (which is how the new National Insurance levy has been sold), it might be excusable. But it’s widely acknowledged, even among ministers, that the policy won’t deliver. Instead the Tories seem to be upping taxes to cover bills they can no longer explain, let alone control.

By the next election, day-to-day health funding will be 42 per cent higher than in 2010. Education, in contrast, will have risen by just 3 per cent. With the promised care-home subsidies, it will be easy to caricature this Tory government as a conspiracy of the old against the young. The conversion to Big State conservatism has come about with no discussion.

Bypassing debate has become a signature theme of Johnson’s government. Cabinet meetings are perfunctory affairs where orders are passed down not discussed. Ministers aren’t asked to contribute insight even into their own departments, but simply informed of the policy they must follow. In private, ministers despair about money pouring into the ‘NHS black hole’ but none dares raise this point. Talking too much in cabinet (even to express support for the Prime Minister) is now frowned upon. In Johnson’s re-shuffles, the loquacious tend to suffer.

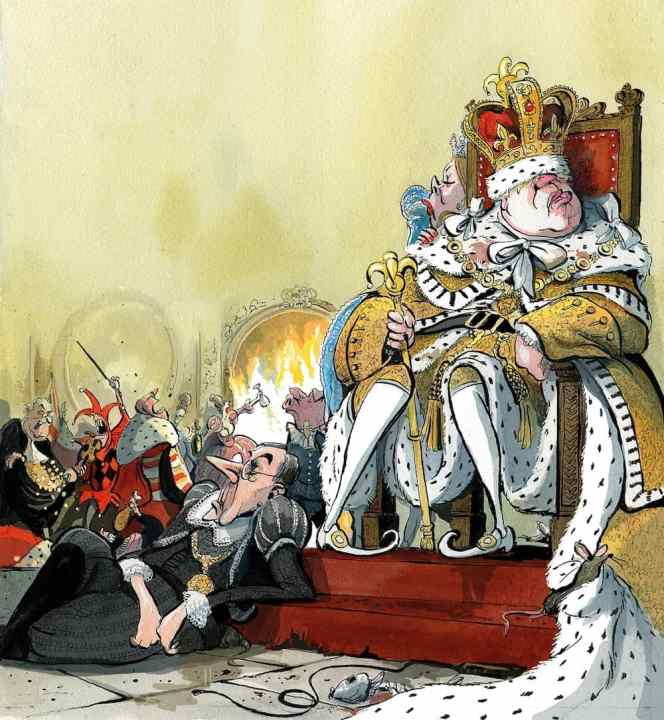

The ageing king sits with his young advisors, often those who are friendly with his wife, Carrie

A rubber-stamp cabinet might have been viable if vigorous discussion happened inside No. 10, but there’s not much debate in there either. The ageing king sits with his young advisors (often those friendly with his wife, Carrie, whose own court is a source of heated intrigue). His long-serving liege Sir Eddie Lister won’t come back from retirement in spite of recent blandishments. ‘No one wants to go near that madhouse,’ says one former Johnson loyalist. So there is no Willie Whitelaw, no Charles Powell, not even a David Wolfson to supply experience, judgment and grip.

The head of the civil service, Simon Case, is at 42 the youngest man to ever hold that position. Dan Rosenfield, the 44-year-old chief of staff, is cut from similar cloth to Case: more civil servant than politician. Neither has the ability to foresee the political dangers or the character to speak truth to power. Rosenfield’s style is to warn of a problem but then keep quiet and consider his duty discharged, rather than sticking to his guns as a more political figure might do. Once the Prime Minister gets an idea in his head, only a public backlash changes his mind.

This is a Napoleonic model of government without a Napoleon, and it serves Johnson very badly. He’s at his best when working with people who challenge him, who know him well enough to separate the inspired ideas from the patent lunacy. In City Hall he flourished after surrounding himself with ‘deputy mayors’ of great quality, to whom he deferred. As foreign secretary he was unable to appoint anyone, and he flopped. In No. 10, he appointed Dominic Cummings. This led to the creation of the megacourt: the Treasury ended up subordinated to No. 10 (at which point Sajid Javid resigned in protest) and together with the Cabinet Office a triangle of power was created, with the Prime Minister at its head. Or so he was told. Cummings has now said that the real agenda was to take power away from Johnson. ‘I was trying to create a structure around him to try and stop what I thought would have been bad decisions,’ he told a Commons select committee, ‘and push things through against his wishes.’ Johnson fired Cummings, but the all-powerful structure remains.

To an extent, this suits him. He hated having the then chancellor Javid telling him what he could and could not spend. Now, he writes large cheques with great abandon. The last Budget showed Rishi Sunak has become Chancellor in the medieval sense of the role: his job is not to set spending limits but to raise however much money the king wishes to spend. Sunak likes to warn about inflation as the kind of force that would not respond to No. 10 edicts. Johnson is unconvinced and talks about spending restraint as ‘austerity’, a curse which he does not wish to inflict upon the country. ‘Levelling up’ has become seen as his code for taxing the south to subsidise the north. But what if the economy underperforms, inflation hits hard, or — even worse — the Bank of England stops playing ball and hikes interest rates, cutting off the government’s source of cheap credit?

A cabinet reshuffle might have reset his government, made it less Boris-centric, but instead it served as a reminder that personal loyalty is the coin of the realm in Johnson’s government. Mark Spencer, the chief whip (and the orchestrator of the Owen Paterson voting debacle), is a good example of someone being kept in post for fealty rather than ability. Nadine Dorries, a longstanding ally, is now Culture Secretary, which will (as Johnson intended) wind up the BBC. But she is in charge of the Online Safety Bill, one of the most delicate and important pieces of legislation the government is trying to enact. Even in No. 10 there is nervousness about this.

With a large majority and a stunningly inept opposition, Johnson can get away with behaving this way up to a point. The King Boris model did work for a while, when it was vital to get Brexit done, and it segued naturally into the era of Covid and lockdowns. But Johnson is simply not cut out to be a great dictator. He has too little real interest in politics. He entertains too many contradictory ideas. He sold himself on consistency and grip, but the manifesto–breaking and general shambles drain his authority. His net satisfaction rating has hit a record low of minus 27 and earlier this week, the Tory poll lead — his strongest source of personal power — vanished entirely.

The promise to protect voters from the rising cost of government was not a small-print pledge but was at the heart of his promise to his new voters. ‘A majority Conservative government will cut taxes for you and your family,’ he said during the campaign — a promise repeated almost every day. ‘We’re lowering your taxes so that you can keep more of what you earn’; ‘A Conservative government will keep your taxes low, not take more away’.

Sir Keir Starmer is perhaps the knight of the realm who serves Johnson the best, ensuring the Labour party poses minimal danger. One of those tasked with thinking about the next election frets that if Labour got a new female leader who campaigned on everyday concerns such as the cost of living, then the Tories would be in trouble. Some Tories dismiss this, pointing out that Ed Miliband’s focus on the issue did him little good. But there is a big change now: polls now associate Tories with higher taxes far more than they do Labour.

Sunak has a plan to recover some credibility on tax, having cut it (or, at least, the Universal Credit ‘withdrawal rate’) for the poorest workers. After a Budget speech that in parts sounded like a hostage statement, he pledged to cut taxes with any extra money that might come in. He has gone further than any other Cabinet minister to acknowledge what (even now) aides in No10 do not: that there has been a serious problem. “For us as a government,” he said, “it’s fair to say that we need to do better than we did last week.” This comes closer to an apology than the Prime Minister has managed. But might Sunak be put back in his box? If Johnson decides to splurge his way out of the next crisis — in whatever form it comes — then Sunak will lose the bigger argument – and his authority.

The obvious remedy is to dissolve the court and replace it with something resembling a government — with power more evenly spread, ideas robustly discussed and flaws identified early. ‘You can be a maverick, but some laws you can’t defy,’ says one senior figure from whom Johnson seeks occasional advice. ‘If you spend, others will pay for it. Hit them in their pocket, they’ll resent you. Break your promises, and they won’t forget.’

One political advisor, Ben Gascoigne, has been lured back but a far bigger rethink is needed. Some of Johnson’s allies say he is bound to recognise, now, that his current system is not working for him — let alone for the party and country. But others think he finds his court too comfortable and thinks his gravity-defying political powers will prevail. His party might have no other choice than to hope that he’s right.

Comments