Even Spectator book reviewers have to concede that their craft is inferior to the creative travail of authors. Henry James railed against the practitioners of literary criticism long ago:

So much preaching, advising, rebuking & reviling, & so little doing: so many gentlemen sitting down to dispose in half an hour of what a few have spent months & years in producing. A single positive attempt, even with great faults, is worth generally most of the comments and amendments on it.

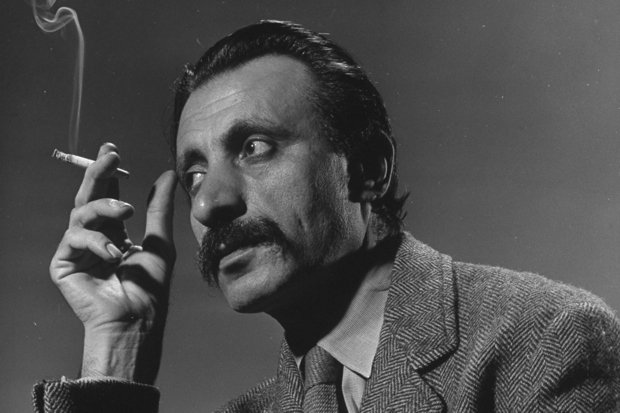

The American critic Malcolm Cowley (1898–1989) escapes these anathemas because early in his long life he was a poet of some distinction. For nearly 70 years, too, he produced essays and books which together constituted a literary history of the United States. He was at the topmost notch of second-rate minds, or (as his dedicated editor Hans Bak might claim) on the lowest rung of the first-rate. Moreover, as Bak’s selection of Cowley’s correspondence shows, he preferred to advise and improve other people’s draft work, or to explain and praise published work, rather than to rebuke or revile. He rehabilitated reputations, promoted new talents, encouraged flagging spirits.

Cowley volunteered in 1917 as a camion driver with the American Field Service, transporting ammunition, barbed wire and trench flooring in France, and wrote austere war poetry that has not lost its power. After the war he shrank from becoming an office-worker or subway commuter: he apostrophised

tin alarm clocks exploding simultaneously in hall bedrooms from the Battery to Yonkers … O explosive clocks you are very evidently the symbol of something.

He studied at Montpelier university as well as Harvard; then hung out in Paris with the Dadaists, befriended Louis Aragon, grew ‘very fond’ of Tristan Tzara, and knocked around with hard-drinking American expatriates including Hemingway and Fitzgerald.

After shifting to Greenwich Village at the height of the Jazz Age, Cowley ran a literary magazine which was classified as pornographic and driven out of business after referring to a woman’s breasts in the plural. As literary editor and chief book reviewer of the New Republic throughout the 1930s, he was one of the most powerful people in literary New York. He recruited such reviewers as John Berryman, Louise Bogan and Theodore Roethke: poems by Marianne Moore, Wallace Stevens, William Carlos Williams and e.e.cummings were published by him.

There is much to admire in his busy, useful life and his clear-headed, jargon-free expositions and appreciations. In the late 1940s he campaigned so effectively to lift William Faulkner’s reputation from the doldrums that Faulkner was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1950. The revival of Fitzgerald’s reputation was similarly masterminded by him. As literary adviser to the Viking Press, he was vital to the discovery of Nelson Algren, Jack Kerouac, Ken Kesey and others. His correspondence is peppered with references to Ernest Hemingway, Allen Tate, Conrad Aiken, Saul Bellow, Eudora Welty, Truman Capote, Robert Lowell and similar luminaries.

Cowley had masculine taste: there is misogynistic sourness about his references to many women novelists. He saw simpering provincialism in women writers where there was none, but liked them least when he thought they were trying to write like men. His letters are blokey, with lots of ‘goddams’ and he-man swearing.

Cowley resembled England’s Bloomsbury set in thinking that ‘the only important matters are friends, books, sex, the cultivation of the mind’. He was a communist fellow-traveller in the 1930s, but never joined the party. As an ardent and informed lover of French culture, he was devastated by the capitulation of France in 1940: it was this, rather than the Nazi-Soviet Pact, which drove him to reject Marxism. Just before Pearl Harbor, he was recruited to Washington as a government analyst. There he was subject to vicious denunciations as ‘a communist, a Godless revolutionist’, and after strenuous but obtuse investigation by the FBI, was forced to resign. Cowley’s correspondence chronicles how progressives were driven from official and academic jobs by allegations of communism only to be replaced by nominees of the Catholic War Veterans. ‘The loyalty purge’ of the McCarthy period was for Cowley ‘the great Irish Catholic job-hunt’.

His letters contain vivid, piercing accounts of the suicides of the poet Hart Crane (who was then the lover of Cowley’s estranged wife) and of the painter Arshile Gorky. He urged that a major university give W.H. Auden a professorship in order to ensure him a steady salary:

Of course he’s Christian, homosexual, and has been seen to blow his nose on his dirty socks — but he keeps his sexual proclivities under cover and is probably trying to change them; he’d buy handkerchiefs if he had a housekeeper, and the real professorial objection to him would probably be his Christianity.

There are excellent throwaway remarks (the ‘occupational disease’ of Symbolist writers is hypochondria, he says) and arresting comparisons, as of Kerouac with Tobias Smollett. We also learn that the Nazis encouraged the circulation of Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind in Vichy France, believing that it would inspire the French to dislike ‘Yankees’. However, the French adored the novel as a picture of another occupied country resisting invaders: in 1945 worn copies were selling on the black market for up to 4,000 francs each, and a clean new copy cost $100.

Hans Bak’s selection of Cowley’s letters will interest anyone with specialised knowledge of American literature during its 20th-century apogee, but the book is not for general readers. Infuriatingly, its biographical footnotes and indispensable glosses are shovelled into a poky, inaccessible oubliette at the back of the book. This is like making a Christmas pudding from suet and flour, but leaving the spices, grated orange, lemon zest and sixpenny bits on a side plate out of reach.

The Long Voyage remains, though, a fine memorial of those high days when book reviewers were not afraid of showing their intelligence and discrimination, and wrote pieces that changed the way the educated segments of nations thought.

Comments