People say cricket is the quintessential English game. Those people are wrong. Cricket may have a longer pedigree, but it’s too boring, too democratic and too honourable to qualify: croquet is the game that truly captures what it is to be English. As any pub quizzer will tell you, Wimbledon started its life in 1868 as the All England Croquet Club, only developing its vulgar sideline in lawn tennis late in the following decade. Its reputation has yet to recover.

Just like cricket, where the game as played on the village green differs from the international game, the echt English croquet is the one played, ideally slightly drunk, in the echt Englishman’s garden. Its idiosyncrasies are what makes it special. For me, the only true croquet lawn in the world will always be the threadbare triangle of grass in the middle of Weston’s Yard in Eton.

A perfect croquet lawn — should such a thing exist — would make the game a cousin of billiards; a thing of unforgivingly precise geometry, governed by the Newtonian rules of particle mechanics. Touch, feel and low cunning would be all but irrelevant. The special joy of the game as played at home is that the lawn is imperfect. This confers a home advantage (you learn how to correct for the slight dent on the approach to the second hoop; you know where clover makes the grass slow; you know which slightly bent hoop won’t tolerate anything but a perpendicular approach) and leads to a proliferation of house rules; which, set correctly, will also confer a home advantage.

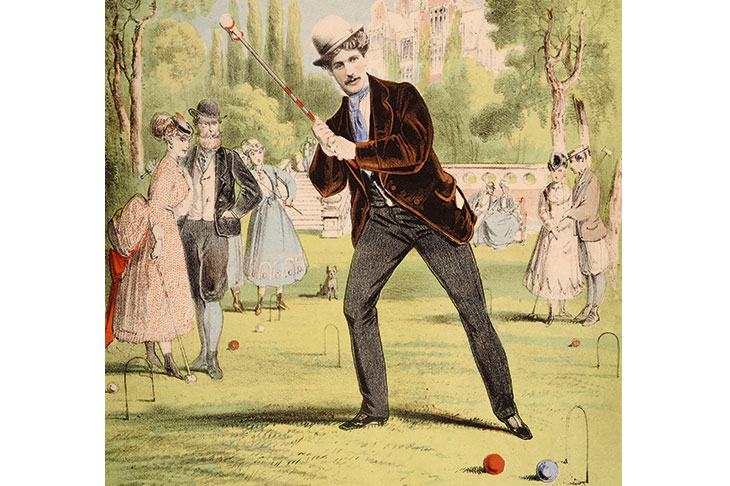

Two no-nos. The golf-shot (mallet perpendicular to feet) makes you look a wally and doesn’t do your accuracy any favours. And putting your foot on your own ball when you play a croquet shot is just awful, and probably against the rules.

Played properly, croquet is the greatest game of co-operation and sabotage to be found on earth. There really is no point at all playing it — as some do — with each player taking a mallet and ball and going it on their own. When you play in teams, the game opens up — it transforms the mallet-and-ball equivalent of snap into a game of contract bridge.

The trick is to leave opponents so far away from you and from each other that any flailing long-distance attempt to roquet your ball is, effectively, a donation of their ball to you for further punishment. The satisfaction of sending your despairing opponent’s ball trundling right up to, but not into, a distant flowerbed… that may be the second greatest pleasure on earth. The greatest being that of quietly, helpfully, patronisingly, putting your team-mate through hoop after hoop without his getting a mallet to his own ball. This really is a ‘zero-sum game’: the less your opponents and even team-mates are enjoying it, the more you will be. Your glory is another’s fury.

Croquet was Auberon Waugh’s game, which says it all. Friends who visited Combe Florey, his Somerset home, report that he was a fiercely competitive player. That is, he cheated like mad — even after having disadvantaged his guests with strong Bloody Marys before play began. That is quite proper. The day the Englishman can no longer cheat at croquet in his own back garden is the day this ceases to be a land fit for heroes.

Sam Leith

Sam Leith

Croquet

issue 29 June 2019

Comments