‘Light as a feather, free as a bird.’ Günter Grass starts this final volume of short prose, poetry and sketches with a late and unexpected reawakening of his creative urge. After peevish old age had brought on such despondency that ‘neither lines of ink nor strings of words flowed from his hand’, he was gripped — out of the blue, and to his evident relish — by the impulse to ‘unleash the dog with no sense of shame. Become this or that. Lose my way on a single-minded quest.’

It makes for an invigorating opening: a three-paragraph paean to the unruly and questioning spirit which drove Grass’s writing throughout his hugely productive career.

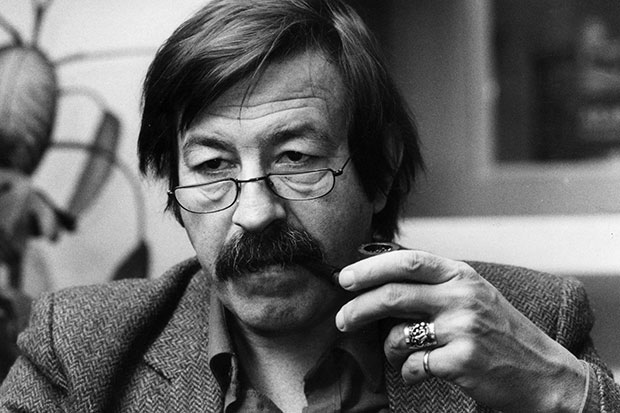

He established himself from the first as a darkly comic force, his 1959 masterpiece The Tin Drum exposing the failures of his parents’ generation with a shrewd and deft storytelling energy. While much of Germany was still licking its wounds, Grass preferred to rub salt in them — and laugh while he was at it. Readers born after the Third Reich were drawn in their thousands to this boldness, the following two volumes of his Danzig trilogy confirming him as the moral compass for a generation of German left-wingers.

An inveterate attention-seeker and political animal, Grass made the most of this status, aligning himself closely with post-1968 reformers; for a time, Willy Brandt, another great idol of the post-Nazi generation, was rarely seen without Grass at his side. By the late 1970s, Grass’s books were publishing events, with enormous first print runs. But while he was beloved of the left, he was never beholden to it, or to anyone. He took aim wherever he saw fit, enraging feminists with his depiction of women in The Flounder (1977); speaking out against reunification in 1990, and the haste and the presumption with which it was conducted; and, in 2012, getting himself banned from Israel over a poem. Like Oskar, his drumming protagonist, he liked to make a big noise — or a big stink, depending on your perspective. Some in Germany saw him as a Nestbeschmutzer, a chick that fouls its own nest. In this volume, he too chooses a bird to describe himself: ‘With Nature’s all-powerful help, I’ve always hoped to be reborn as a cuckoo, drawn to the nests of others.’

Metaphors always loomed large in Grass’s writing, Peeling the Onion, the title of his 2010 memoir, being a case in point. The book was notable primarily for disclosing his teenage membership of the Waffen- SS, the lateness of this revelation causing outrage, given the moral status he’d so long enjoyed and exploited — not least because it formed a key part of the advance publicity. Distasteful as this was, perhaps, as the title suggests it was just such layers of experience, and of silence, which allowed his early fiction to be so insightful.

For decades, Grass was rarely out of the German national conversation, and his literary success and his ability to hog the limelight often overshadowed fellow writers of his notably brilliant generation, especially Siegfried Lenz, Stefan Heym, Christa Wolf, and his fellow Nobel Laureate Heinrich Böll. Little wonder there was resentment. Walter Kempowski noted that, in interviews, he would inevitably be asked about Grass, while Grass was rarely asked about him. I imagine Grass was rarely asked about anyone other than himself, his latest publication or intervention more than enough to provide ample copy.

It is not Grass’s fault, of course, that journalists turned to him at the exclusion of others. He was unfailingly interesting, even when he was being pompous or falling from grace. But he certainly courted, and perhaps also came to feel he deserved, such attention. It is notable, in any case, that the only one of his literary contemporaries he mentions in this volume is the poet, editor and translator ‘our Hans Magnus’ Enzensberger and his verses about clouds. Not to praise, you understand, but to offer a rather spiteful analogy: ‘He loves how they bow first to one wind and then another.’

Two artist friends from Grass’s younger days appear in these pages. Franz Witte found early acclaim as a painter, but suffered repeated bouts of severe depression and died young; Horst Geldmacher produced murals, interiors and public artworks, and became something of a local Düsseldorf legend before his own early death; both, it is said, gave rise to characters in the Danzig trilogy. But Grass had left Düsseldorf and its postwar art scene even before The Tin Drum was published, and here describes it critically: ‘a pleasingly fake bohemia’ that ‘had rid itself of memory’. His old friends don’t come off much better: ‘genius going to waste’. The first stanza of ‘Farewell to Franz Witte’ is fond: ‘Where did you go? Leaping nimbly through the window/of the mental institution/as I see you still’. But ultimately, it is unclear if Grass regrets his friend’s pain, or is merely berating him for not amounting to anything in his eyes.

The intellectual company Grass preferred to keep in his last years was of a more exulted order: Jean Paul, Rabelais and Henry James are all referenced here, often obliquely, as if to let only the reader sufficiently in-the-know into this erudite circle. In one prose meditation, suffering from insomnia, Grass finds Claude Lévi-Strauss (‘a scholar of myth, already ancient in his own lifetime’) knocking on his study door in the small hours. Grass confesses to having appropriated metaphors (what else?) from The Raw and the Cooked — and to never having acknowledged the debt. Lévi-Strauss, gracious to a fault, tells him he stole well and wisely, and encourages him to steal more; there are ‘still merry tales to tell’. Of course Grass had his tongue in his cheek when he wrote this — but then he was always best taken half in jest, all in earnest.

Grass does, however, also turn his critical gaze on himself. Decay and decline are the obvious preoccupations of the pencil and charcoal sketches in this volume: dried frogs and fungi, rotting windfall apples, bent coffin nails. Striking more for their subject-matter than for their execution, the drawings enlighten nonetheless: among the most distinctive are those of a mutilated hand, fingers lopped off at the knuckle by huge scissors, cast iron and menacing.

It is a painful image, and one which speaks volumes. Grass’s greatest regret seems not to have been that life per se is finite but that creativity is too, and the loss of his earlier deftness grieved him. The idea of autumn is returned to again and again in these pages — in all its colour, abundance and rot — primarily for Grass to expresses his frustration at this final phase of his writing.

There’s a clearance sale on metaphors. Openings of novels, final lines…. A plot scurries off: a pile of fallen poplar leaves leads to a crime story whose ending is still unclear. And over all wafts the decaying breath of fall.

Less angrily, comparing the work of a writer to Sisyphus rolling his boulder, Grass tells us his own stone is gathering moss, waiting for ‘someone strong enough to move it’. He still dreams of rocks, but ‘smaller ones, pleasing to the hand’.

One such small act of persistence is ‘How and Where We Will Be Laid to Rest’: four pages of wry and crisp prose, in which Grass details the preparations for death he and his wife make together. Calling in a joiner they know well, they work out the best wood and plainest possible designs for their coffins, preferring leaves from the garden to more opulent linings, sealing the agreement with a homemade schnapps. ‘“We can count on him,” my wife said. “He has always delivered on time.”’

He was not given the energy — or the subject-matter — to make his final volume one of note. Grass was well aware of this, anticipating his critics as ‘cowards yapping from the back of the pack’. But in spite of this, ‘writing still satisfies an itch’, and he assures us ‘the last word’ will be his. For all the yapping I have done here, I agree. It may not be in these pages, but it is contained, without question, in his other works — above all in his first. Grass was a pricker of consciences and of bubbles, a mischief-maker, master of hypocrisy and of metaphor. And he wrote The Tin Drum: enough said.

Comments