Lord Palmerston is remembered today not for his foreign policy nor for his octogenarian philandering, but for his management of the press. He was the first prime minister to grasp that dealing with journalists was all about pragmatic negotiation and buttering people up. The deal between Palmerston and the newspapers was: ‘I’ll tell you something no one knows if you give me your support and a favourable report.’ It still works like that today.

Most historians assume that Palmerston was the only Victorian prime minister to cultivate the fourth estate. Balfour loftily boasted that he never read the newspapers. But this was an affectation. As Paul Brighton shows in this new study, 19th-century prime ministers all had contacts with the press. We just don’t know about them.

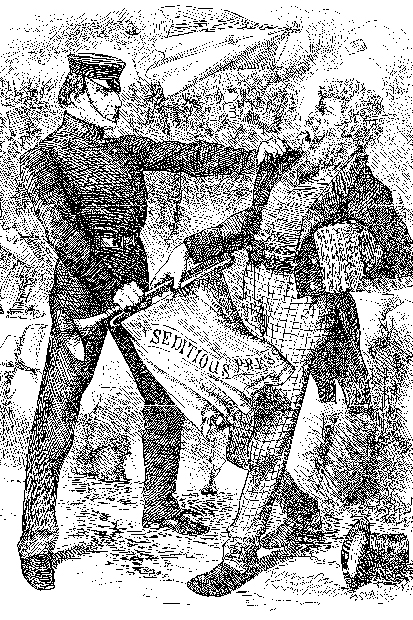

The shady nature of the relationship meant that much of the communication between politicians and the press was not written down, and the evidence is patchy. Journalism in the 19th century enjoyed a far lower status than it does today. Salisbury made his living out of articles for the reviews in the early part of his career, but he wrote anonymously, and he kept it secret. As prime minister he played the part of an absent-minded patrician who disdained the press, but behind the scenes he managed it pretty skilfully.

The official biographers of eminent Victorians treated journalism like a bad smell and left it out of their tombstone Lives and Letters. This was ironic in a way, as many of the great political biographers — Mony-penny and Buckle on Disraeli or John Morley on Gladstone — were themselves journalists by profession, as indeed is Thatcher’s biographer Charles Moore.

The main reason why historians have skated over the relationship of Victorian PMs with the press is that they haven’t been looking for it. It takes a lecturer in media studies such as Paul Brighton to point out that media management was part of the job of a Victorian prime minister.

Not all Palmerston’s successors were as successful at it as he was. Disraeli tried to make his name as a young man through a series of newspaper ventures, all of which were more or less disastrous. Even when he had reached the top, he was interested in the performance of journalism — achieving fame through his writing — as opposed to businesslike management of the gentlemen of the press for the advantage of his party.

Gladstone was very different. He is the most interesting media manager of the prime minsters assembled here. As a politician who adopted a high moral tone, he seemed above making dirty deals with Fleet Street. In fact, he was an effective press manager. He was also an innovator. At the time of the Bulgarian Horrors, when the Turks massacred Christians, Gladstone mobilised opinion through working the provincial press (a new tactic), writing a bestselling pamphlet and addressing packed-out mass meetings. At the 1880 election he made his Midlothian campaign of speeches a media event — this was the very first attempt to win an election through the media. And in 1885 his son Herbert delivered one of the most spectacular press leaks ever, when he told the press that his father had converted to Home Rule for Ireland.

The early chapters of the book, which chronicle the press dealings of prime ministers from the Younger Pitt, who attempted to control opinion by instructing the press or by buying government newspapers, are rather textbook-like. But Brighton has interesting things to say about the evolution of press management from Palmerston onwards.

Comments