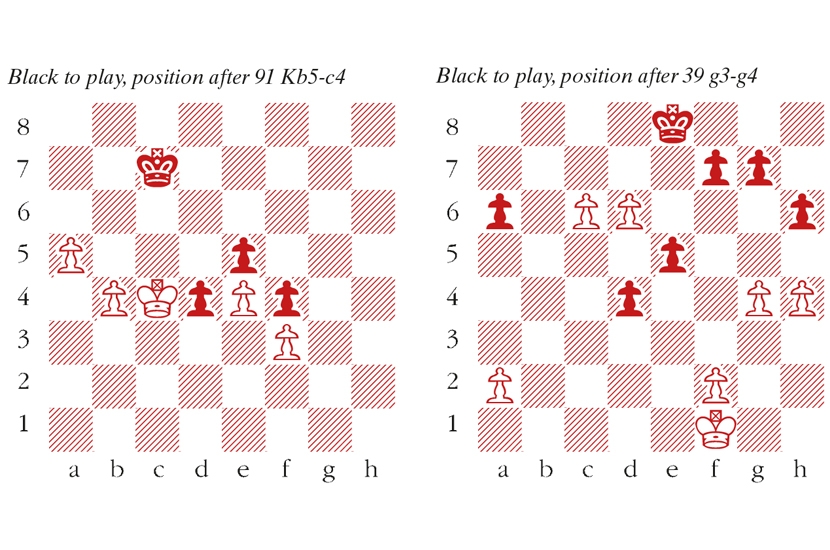

The fifth match game between Potter and Zukertort, played in London in 1875, saw a dogged struggle. The final position is shown in the diagram below, where the players agreed to a draw after 91 Kb5-c4. William Norwood Potter, an English master, must have reasoned as follows: the protected passed pawn on d4 obliges the White king to stand guard. The passed a- and b-pawns cannot overcome Black’s king on their own, and so a draw is inevitable.

But Potter missed a splendid winning idea, in which the White king makes a heroic charge up the board. An illustrative variation: 91…Kc6 92 b5+ Kb7 93 b6 Ka6 94 Kb4 Kb7 95 Kb5! d3 96 a6+ Kb8 97 Kc6 d2 98 a7+ Ka8 99 Kc7 d1=Q 100 b7+ Kxa7 101 b8=Q+ Kxa6 102 Qb6 mate!

There is no room for error in this kind of operation. For example, in the line above 93 a6+? would throw away the win, and then 93…Kb6 94 Kb4 Ka7 95 Ka5? even loses as White is a tempo behind the pace: 96…d3 97 b6+ Kb8 98 Kb5 d2 99 Kc6 d1=Q

Le Quang Liem–Leinier Dominguez

New in Chess Classic, April 2021

An exciting situation occurred last month (see diagram 2, Black to play). Imagine sweeping away all the f, g and h pawns: the position is then drawn. Black will place pawns on e4 and d3, so that a bolt forward with the White king (as in the previous example) would be too slow. However, if Black plays 39…e4 in the diagram, White has a methodical winning plan, making use of the f2-pawn. First, 40 h5! to fix the kingside pawns, so if Black ever ventures …g7-g6, the response g4-g5! will engineer a decisive passed h-pawn. Next, trundle the king round to b3 and c4, and back to c3 when Black advances d4-d3. (White must be sure to meet …a7-a5 with a2-a4, to retain access to the b3-square). Finally, dismantle Black’s e4-d3 mini pawn-chain with f2-f3. Instead, Black could start with 39…g6. But then 40 g5! nails down the f7-pawn, and the same plan can be enacted. An alternative defensive idea is 39…f6, since the g7-f6-e5-d4 pawn chain can never be undermined. But it is too far back, so White has a win in the style of Potter-Zukertort, e.g. 40 h5 Kd8 41 f3 Kc8 42 Ke2 Kd8 43 Kd3 Kc8 44 Kc4 Kd8 45 Kc5! d3 46 Kb6 d2 47 Kb7 d1=Q 48 c7+ Kd7 49 c8=Q+ Kxd6 50 Qd8+ with a decisive skewer. Dominguez took just seconds to play the only drawing move. He played 39…h5!!, aiming for a safe connected trio f5/e4/d3. If 40 g5 f5! 40 gxf6 (en passant) gxf6 41 Ke2 e4! is just in time, with f6-f5 to follow. Or 40 f3 hxg4 41 fxg4 e4 and the pawn duo is safe. Le tried a clever idea, 40 Ke2. Now if Black tries to win, he actually loses, e.g. 40…hxg4 41 Kd3 Kd8 42 Kc4 Kc8 43 c7 f5? (Black must not allow a future Kd5-e6). 44 Kc5 Kb7 45 Kd5 d3 46 Ke6 d2 47 Kd7 d1=Q 48 c8=Q+ and the d6 pawn will soon win the game. Dominguez wisely ignored the bait, and after 40…e4 41 gxh5 f5 42 f4 d3+ 43 Ke3 Kd8 it was Draw agreed a few moves later.

Comments