It must have been awful for Diana and Duff Cooper to be separated from their only child during the war, but we can be grateful for it because it’s a joy to read the correspondence it gave rise to. The letters in this book span the years 1939 to 1952 and take in the Blitz, Diana’s short spell as a farmer in Sussex, a trip to the Far East, when Duff was collecting intelligence on the likelihood of a Japanese invasion, the couple’s three years in the Paris embassy, and several more in their house at Chantilly, as well as a great number of journeys around Europe and North Africa.

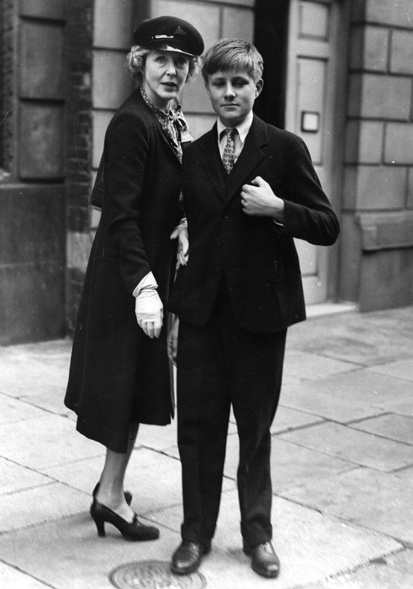

The most charming thing about the war letters is how grown-up they are. John Julius Norwich was sent to safety in America and hardly saw his parents for two years. His mother sent letters nearly every day, writing to him when he was ten in exactly the same way as she did when he was 20. Diana never seems to shy away from a complicated story about politics or marriage or a literary reference.

She’s also very open about the horror of the bombs, the sleepless nights and constant fear, but she keeps it light: ‘A bomb fell at the feet of the Abraham Lincoln statue and only 20 yards from me in the canteen. I didn’t half jump.’ She complains of ‘such acute bombitis of the ears that if my inside rumbles I jump out of my skin and think it’s air activity, which indeed it is.’

Occasionally she hesitates: ‘Papa read my last letter to you and tried to stop me sending it. He said it was quite unintelligible to a boy of 11, or to an adult for that matter.’ Luckily she carries on just the same, and she was right to; the few short letters of his own that John Julius has included show what a happy correspondence they had, and she had a genius for clear anecdotes and vivid description. The ballet dancer Moira Shearer, for example, is ‘most exotically beautiful — real scarlet hair and ashen colouring and huge murky blue eyes like the unsettled colour of newborn things and of a slenderness to break and snap like a tulip.’

The famously beautiful and stylish Diana paints a picture of herself as a scarecrow figure during her farming years. When her cow escapes, she sets off in her nightcap and huge rubber boots to coax it home. Examining her hives with a local bee-fancier, she realises that the inside of her trousers has become lined with bees. So she calmly removes them, finding herself ‘exposed in ridiculous pants, pink as flesh. It was a C. Chaplin scene.’ She doesn’t blame the soldiers who stop her from entering the house where Winston Churchill was staying, explaining that, ‘I look very funny in the country these days in brightly coloured trousers, trapper’s fur jacket, Mexican boots and the refugee headcloth …They thought, no doubt, that I was a mad German assassin out of a circus.’

Duff Cooper’s affairs were well known, but somehow the lovers didn’t undermine his wife. These letters never acknowledge any mistresses, but there are a lot around, including Susan Mary Alsop, pregnant, it later turned out, with Cooper’s child. John Julius says that his mother only minded when she considered a mistress unworthy. He remembers her saying: ‘Mind? Why should I mind if they made him happy? I always knew: they were the flowers, I was the tree.’

A very touching picture of their marriage emerges in these letters. On quiet evenings the Coopers did the crossword together and read Trollope aloud; Diana didn’t ‘like a breath of criticism’ where Duff was concerned, and when he was ill she would be beside herself, and he would play ‘kind little tricks’ to reassure her, like ordering a drink and pouring it away when he thought she wasn’t looking.

There’s a sweet scene during the Blitz when they lived at the Dorchester hotel and the air raids meant that they didn’t get as much time alone together as they might have wished for:

The All Clear went so early, and when Papa and I went down to the gym it was empty quite, so we talked for half an hour in ordinary voices and discussed a multitude of things and people, and joked in our own domestic way with phrases and nonsense language, and time-worn but loved ridiculousness. When nobody appeared to be coming down I got up and went round turning out the lights by other beds. To my horror, by a bed that had no light, and which is rarely if ever occupied, I saw the bright, beady eyes of Miss Cazalet darting out of the face with interest and horror at our conversation.

The book ends before Duff’s death in 1954, but it leaves one with a sense of what a terrible blow it was. Poignantly, in the later letters, Diana worries more and more about his health, her happiness entirely dependent on his energy and appetite.

A perfect ambassadorial couple, the Coopers knew everyone; Hilaire Belloc, Evelyn Waugh, Nancy Mitford and Winston Churchill make regular appearances, and Diana always had an interesting take. Graham Greene, she wrote, is ‘a good man possessed of a devil’, while Evelyn Waugh is ‘a bad man for whom an angel is struggling’. Their circle of friends and their unusual marriage add to the impression that they inhabited a lost world — a world of old-fashioned manners and hordes of servants (often very troublesome ones) and of travelling around on trains. Funny and warm and eccentric, these letters are a wonderful record of a kind of life that has quite disappeared.

Comments