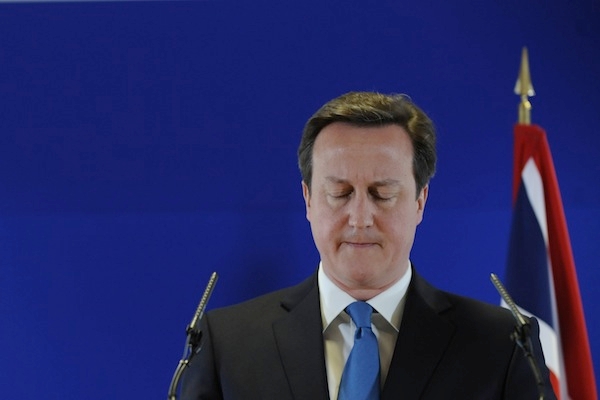

For David Cameron, Margaret Thatcher’s funeral must seem an awfully long time ago. Back then, all the talk was of a new Tory unity. He had found a way to connect with his troops. The party seemed to be rallying behind his electoral message. Labour, meanwhile, was caught on the wrong side of public opinion in the welfare debate. And there were signs that the economy was — finally — beginning to recover. Cameron’s position appeared stronger than it had at any point in the last 18 months.

Three weeks later, he is undergoing the most profound crisis of his leadership so far. Tory unity has evaporated over Europe, gay marriage and whether the top brass think the membership are ‘loons’. All the pressure on Labour has lifted. The story is Tory divisions again: nearly every news programme features two Tory MPs arguing with each other. The situation, as one Tory cabinet minister nervously puts it, ‘has more than a hint of the John Majors’.

There is an industrial quantity of blame to go round. One No. 10 source concedes that their operation has been ‘arrogant and incompetent’. Cameron cancelled two political cabinets in a row — so there was no collective consultation with his senior colleagues as the fights raged over Europe and gay marriage. During this time he also failed to meet any member of the 1922 Executive, the MPs elected by Tory backbenchers to represent them. Any leader who cuts himself off from his party in these circumstances is foolhardy, to say the least.

Then there is the ‘swivel-eyed’ saga. Whether or not party chairman Andrew Feldman actually used the words remains the subject of intense dispute. But the accusation and the fallout from it highlight several things that are wrong with the way that Cameron does politics. The alleged remark caused such a stir because it seemed to fit the disdainful attitude that too many Cameroons take towards their party; that the foot soldiers fail to appreciate what good leaders they have. As one senior backbencher puts it, the leadership ‘blames other people for failing to be inspired by them, rather than themselves’.

Compounding the problem is the narrowness of the clique around Cameron. Andrew Feldman might be an able fundraiser but he is the joint chairman of the Tory party because he is friends with the Prime Minister. They played tennis together for their Oxford college, Brasenose. Cameron appears unwilling to trust anyone he met after his first months as leader of the opposition. And so his inner circle fails to draw on all the Tory talents.

The other fault that the saga revealed is that the No. 10 operation is simply not nimble enough. The story broke in Saturday’s papers. By Monday’s, Ukip had a full-page ad in the Daily Telegraph calling on disaffected Tories to switch sides. But it took until late on Monday afternoon for Cameron to send a bland email of reassurance to party members. If the leadership wanted to manage this crisis proactively, that email should have gone out on Saturday, straight after Feldman’s denial. If Cameron wanted to show that he really did value the party’s grass roots, he should have written by hand to every Tory association chairman — that would have had far more of a impact than a mass email.

But it would be unfair to blame No. 10 alone. There’s a small but growing band of backbenchers whose personal hatred of Cameron means that they will do almost anything to harm him, regardless of the effect on the party. There can be no appeasing these people. But intelligent management could split them off from the party’s mainstream.

More worrying for No. 10 is the willingness of senior figures to fan the flames. It is hard to overstate how angry some of Cameron’s confidants are with Philip Hammond, the Defence Secretary. They feel that his recent pronouncements on the EU, gay marriage and the need for welfare cuts are all designed to position him as a potential answer to the question, ‘If not Cameron, who?’ Bastards, the term John Major applied to his cabinet troublemakers, is mild compared with what the Cameroons say about Hammond.

There is also no doubt that politics has become more difficult. The Tory party used to believe in loyalty. But now those MPs who rebel can expect to be lauded when they return to their constituency associations. The media environment has also become more febrile. As newspapers struggle for financial stability, they have become ever more aggressive. According to one Tory who has watched both Major and Cameron operate at close quarters, ‘Cameron would have breezed the 1990s.’

Where all the Tory discontent will lead remains to be seen. A confidence vote on Cameron’s leadership is becoming a more substantial prospect. It would still be a surprise, but, as one senior figure notes, ‘If the Cameron inner circle was trying to build the pressure up for that, they couldn’t be doing a better job.’

The situation facing Cameron, though, is different in two crucial respects from the one Major faced. First, there has been no Black Wednesday. However far George Osborne has veered from his original deficit reduction plan, he has not been forced to admit that his economic strategy was wrong. So the Tories have a good chance of claiming credit for an economic recovery. Government insiders are convinced that the next two years will see steady, if unspectacular, growth. They believe that this will make politics far less scratchy and give them a substantial lead over Labour on the economy.

Second, there’s no Tony Blair on the scene today to snap at prime ministerial heels. In terms of pure political skills, no one in this parliament comes close. But Blair was also prepared to win by closing down the right’s potential advantages. In the 1997 manifesto, he promised to keep to Tory spending plans for the first two years of a Labour government, not to raise the basic or higher rate of income tax and to hold a referendum before Britain joined the single currency. Ed Miliband, by contrast, doesn’t want to match Tory pledges on spending, welfare and EU referendums. He has set himself the far more difficult task of winning a mandate to govern in a distinctively Labour fashion.

The Tories need not despair. Defeat is not inevitable. But if the leadership and the Tory party cannot find a way to work together, it will soon become so.

Comments