The Amazon reviews for David Deutsch’s The Beginning of Infinity don’t alert you to the fact that this is a book on theoretical physics. They sound more like a weepy divorcé’s YouTube comments below a Mark Knopfler guitar solo. ‘I didn’t so much read it,’ says one. ‘It read me.’ ‘I was honestly sad when it was over,’ writes another. ‘This book changed my way of seeing the world, politics, science and, most importantly, of seeing what I will understand as containing some truth.’

When I talk to Deutsch – one of the most sensationally interesting theoretical physicists of our age – on Zoom, I see two beady eyes peering at me over some non-spectacular spectacles under a mess of thin white hair, borne by a thin white man in a thin white shirt. Aged 72, he still has the enquiring look I imagine he had at five years old, when, he tells me, he knew he ‘wanted to be some kind of scientist’.

He made a name for himself in the 1980s when he established the first formal model of a quantum computer

Mystical though his manner and his research are, his ideas must be taken with the utmost sense of seriousness and wonder. When the New Yorker profiled him in 2011, he told them: ‘I can’t stop you from writing an article about a weird English guy who thinks there are parallel universes. But I think that style of thinking is kind of a put-down to the reader.’ The first line of the article duly read: ‘On the outskirts of Oxford lives a brilliant and distressingly thin physicist named David Deutsch, who believes in multiple universes and has conceived of an as yet unbuildable computer to test their existence.’ Suggestion somewhat ignored, then.

Deutsch’s contributions to the field are legion, and his career is impressive. He still lives in Oxford, and is a visiting professor in the department of atomic and laser physics. He has written two books, both with titles that testify to the vastness of what he’s grappling with: The Beginning of Infinity in 2011, and before that, The Fabric of Reality in 1997, about quantum mechanics. As a researcher, he made a name for himself in the 1980s when he established the first formal model of a quantum computer. He’s known more now for his unwavering advocacy of the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics, a theory (he would certainly dispute that word) that supposes there is a vast number of universes out there, from ones where you broke your leg on the way back from the shops this morning, to ones where you are the richest person in the world. He is not short on confidence and humour either: at the end of his most recent book, a shortlist of things that ‘everyone should read’ contains two of his own works.

He is adored, and I mean adored, in Silicon Valley, where OpenAI’s chief Sam Altman describes the first chapter of The Beginning of Infinity as ‘the most wonderfully optimistic take on why, even in a world with AI, we’re never going to run out of things to do’. It is, he has said, his favourite book. At an event earlier this year, Deutsch had a chat over Zoom with Altman, whose eyes, bulging even more than normal, communicated immense respect.

Deutsch was born into a Jewish family in Haifa in 1953, the fifth year of the state of Israel’s existence. Both of his parents’ education was ‘thwarted by the Holocaust, so neither of them went to university’. They moved to London and ran a restaurant called the Alma on Cricklewood Broadway. Deutsch rushes through his childhood procedurally: ‘I went to a local primary school, which was disgusting, then to a grammar school, which was less disgusting, then to Cambridge and then Oxford.’ Once we are on to science, we’re OK.

I mean ‘science’ in the truest sense of the word, in the way the Greeks might have understood it: rejecting subdivisions of methods of enquiry, and focusing on the ultimate question of knowledge. His writing and research interests have led him away from the particulars, and on to the universal. He takes after his intellectual hero Karl Popper, and is obsessed with how we come to know things and what more we might be able to know. The writer Tyler Cowen has said that Deutsch is ‘the world’s first true philosopher of freedom’, in that he detests arguments that ‘postulate barriers to human knowledge’. The Beginning of Infinity claims that since the Enlightenment, humans have potentially put themselves at the beginning of an infinite sequence of knowledge creation.

His is an unashamedly human-centric philosophy, one that rejects woo-woo about our insignificance. He writes that: ‘We have never merely been [the Earth’s] passengers, nor (as is often said) its stewards, nor even its maintenance crew: we are its designers and builders. Before the designs created by humans, it was not a vehicle, but only a heap of dangerous raw materials.’ I’m reminded of the old joke of looking out at the infinite stars in the night sky and realising how insignificant they are compared to me.

Before the Enlightenment, he says, nobody ever experienced progress within their own lifetimes

The Enlightenment is the crux, he says, because beforehand, ‘knowledge was increasing at a rate too slow for individuals to recognise in their lifetime. Nobody ever experienced progress. Sometimes they experienced change which turned out to be for the better, like if a bad king died and was replaced by a good king. But they still didn’t conceive of change in the way that we do now, in hoping that one’s children will live a better life’. In The Beginning of Infinity, he describes the Enlightenment as a ‘rebellion against authority in regard to knowledge’, which is gorgeously neat.

Of course, the Enlightenment’s gifts don’t feel infinite right now. Firstly, there is a technological stagnation warned of by people like Peter Thiel, who has said: ‘We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters.’ Deutsch agrees that ‘there is stagnation in some respects that are important to me and important to Peter Thiel, for example, in fundamental science… if you think of medical science and cosmology, astronomy and quantum physics, the progress has been far too slow.’ Even with AI, he says: ‘The community is kind of hyping AGI [artificial general intelligence, where AI matches human ability across all cognitive tasks], which I think it is nowhere near achieving. The existing large language models are not the way to achieve it.’ He thinks that they certainly can appear human-like, but there are ‘people who anthropomorphise their pets. It doesn’t mean there is anything human-like in their thinking’.

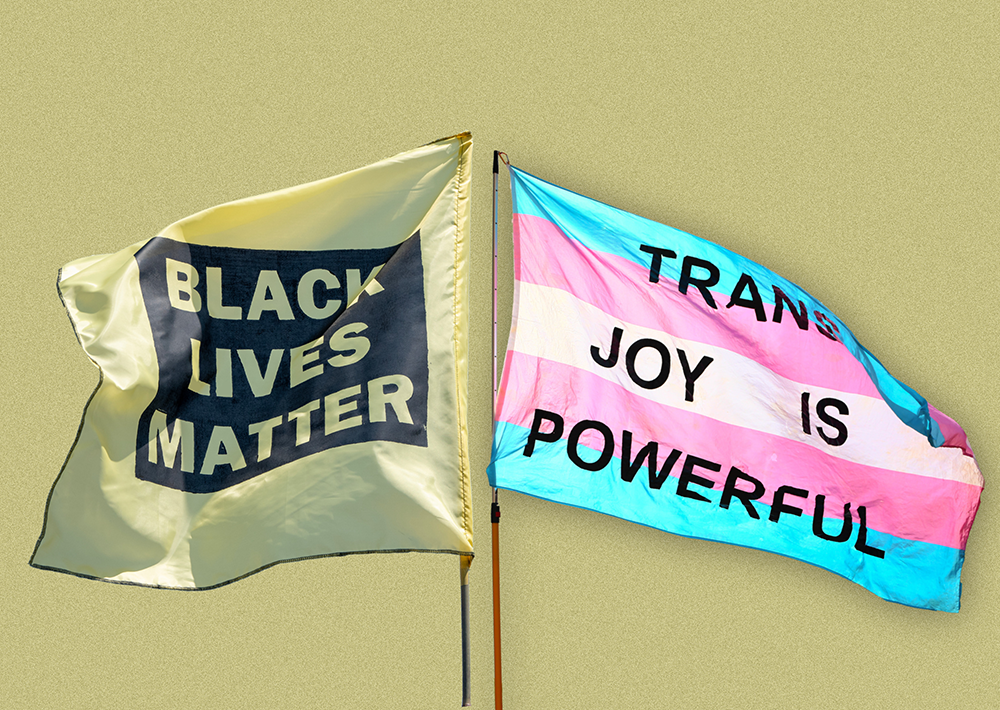

Secondly, there is the prevalence of what Deutsch calls ‘irrational memes’. Rational memes are ideas and concepts that survive scientific scrutiny. Irrational memes, however, reproduce by disabling the capacities of their hosts to evaluate or invent new ideas. One that Deutsch has spoken about several times is anti-Semitism, which he says to me has been a ‘feature of the opposition’ to the Enlightenment for several hundred years. ‘I think that “anti-Semitism” is a misleading term because it casts it as a kind of racism or bigotry. It’s more of a moral pathology, which is extremely old. It’s at least 2,500 years old and comes up again in modified terms every couple of generations… we’re in the middle of a massive outbreak of it now.

‘But let me say, before we get too pessimistic, I think at the moment there is also something else completely unprecedented happening, unprecedented in the last 2,500 years. There is a mass movement of resisting anti-Semitism or resisting the pattern that has never happened before.’ I ask him who he’s thinking of, and he’s hesitant to say. ‘I don’t want to single out particular individuals, because then the ones that I don’t mention will be slighted.’

Deutsch speaks more moderately than his X feed suggested to me that he would. Surprisingly for an Oxford academic, there’s retweets of Suella Braverman and Eylon Levy, along with plenty of disquiet about things like the Chagos Islands handover. In conversation, he is more reserved. ‘We happen to have a very bad government at the moment,’ he says, although ‘nothing in what’s happening currently makes me think that it can’t be corrected. The Anglosphere political culture is par excellence a culture that corrects mistakes. It’s also a culture that makes mistakes. That’s not a coincidence. Rational processes are processes that make more conjectures, test out more ideas and therefore make more mistakes and larger mistakes. But the thing is, good cultures correct good mistakes.’

‘Multiculturalism prevents all the things that make immigration a good thing from happening’

I wonder what a ‘good culture’ is, and ask him whether Britain is one. There are trade-offs to be made in a multicultural society: does immigration undermine cohesiveness, or does it furnish us with greater diversity of knowledge? ‘Well, multiculturalism is a system of reducing intellectual diversity and making for a monoculture. It’s not literally a monoculture yet, but that’s the thing which is mostly holding up progress… On the 50- or 100-year time scale, I’m in favour of immigration. I myself am an immigrant. But I think that the set of doctrines called “multiculturalism” systematically prevents all the things that make immigration a good thing from happening. In the past, Britain absorbed waves of immigrants, and it was beneficial because the main culture did not try to alter itself to accommodate the immigrant culture. And it was taken for granted that there was one law for all. Now we have a two-tier system’ – he chuckles – ‘allegedly! But in the political sphere, consent is more difficult to achieve, and criticism is more and more suppressed.’

The fix to all this dysfunction, he says, could have been that somewhat forgotten thing: Brexit. Deutsch supported Leave, to the extent that there is now a section of his Wikipedia page marked ‘Views on Brexit’. His opinions on the matter weren’t revolutionary, but were consistent with his occupation with rationality: ‘The EU is incompatible with Britain’s more advanced political culture… error correction is the basic issue. I can’t foresee the EU improving much in this respect.’ He later said that ‘Europe is structured in such a way that it’s very difficult to know whom to address your grievance to.’

Now, he laments that: ‘We haven’t yet made much use of the freedom to innovate that leaving the EU created… The political class has been stultified, both institutionally and literally, by a long period of membership of the EU, where politicians, the ruling class and civil servants systematically divested themselves of responsibility for anything.’

I get the sense that stasis offends Deutsch: at the end of The Beginning of Infinity, he says that ‘stagnation does not make sense’. He speaks with genuine sorrow about a realisation he had about Wikipedia recently. On his computer, he keeps a list of examples of progress happening that he hadn’t thought were achievable. The world wide web is one example: ‘I couldn’t imagine that the authors of all the trillions of documents in the world would go to the trouble of converting them all to HTML.’ Yet earlier this year, he had to delete Wikipedia from the list. ‘I originally thought it couldn’t possibly work, and then I added it to the list when it appeared to work very well for years. Now… it’s succumbed to the woke plague. I’ve avoided using it for several years now, and I crossed it off the list.’ He sighs. ‘I was right the first time.’

All this political chat is caveated with the phrase ‘I’m not an expert’. And technically, yes, Deutsch is not an expert on Whitehall, or Wikipedia’s editorial content policy, or Britain’s withdrawal agreement with the European Union. Yet he very evidently does have expertise, and it lies in topics no less significant than thought, rationality, progress, science and knowledge. If he is not qualified to weigh in on something marginally outside his purview, then we might as well give up. An instinct, I’m sure, that Deutsch would have little time for.

Comments